Animal rearing is a vital economic activity in India. According to the Economic Survey of India 2023–24, it contributes 30.38 percent to the total gross value added (GVA) of agriculture and provides employment to more than 30 million people. In addition, India’s total livestock population is approximately 535.78 million, and more than 70 percent of rural households in the country maintain domestic farm animals. The Situation Assessment Survey (SAS) 2021 reports that animal husbandry, dairying, and fishing serve as stable income sources, adding 15 percent to the average monthly earnings of agricultural households.

However, many animals are lost due to disasters every year. Some 45.25 percent of livestock (including buffaloes, cattle, goats, and pigs) are vulnerable to floods, while 44 percent are affected by droughts and cyclones. Unfortunately, there is no available data on the number of companion animals, such as stray dogs and cats, that perish in disasters.

For pastoralists, the thought of leaving their animals behind during a disaster is often unbearable, if not unthinkable. Yet when disaster strikes, many are left with no choice. During the 2018 Kerala floods, for instance, many people—hoping to return soon—were forced to leave their animals out in the open or tied up. They came back to find the animals’ bloated bodies after days of being submerged in water that had risen to roof level.

Similar stories echo across Assam, Odisha, West Bengal, and other places where Humane World for Animals, the organisation I work with, has provided relief in previous years. The bond between pastoralists and their animals goes beyond economics; it is emotional, cultural, and deeply ingrained in their way of life. These communities’ disaster resilience depends on the safety and welfare of animals, often ignored in disaster management efforts.

The gaps in the existing system

While India’s disaster management system has matured over the past two decades, particularly after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, the inclusion of animals in the public policy framework remains inadequate overall.

Here are some steps taken at the national level:

- The National Policy on Disaster Management 2009 sets the foundational tone for disaster management in India. It includes a critical clause that recognises the importance of saving animals during disasters, outlining basic responsibilities such as providing shelter, feed, and post-disaster care. This was a milestone as it marked the formal inclusion of animals in a national-level disaster framework for the first time. However, the policy is more of a vision document and lacks operational clarity. It does not define institutional mechanisms to implement animal-inclusive response systems across states. There are no structures for budget allocation, legal enforcement, or technical guidance. As a result, while the policy sets a necessary precedent, it falls short of enabling the functional integration of animal welfare at the district or panchayat level, where disasters strike the hardest.

- The National Disaster Management Plan 2019 builds on its predecessor by aligning more closely with the Sendai Framework and introducing a broader lens of disaster risk reduction. Importantly, it contains dedicated sections (2.5 and 2.6) that recognise the significance of protecting livestock and domestic animals in building community resilience. It recommends adopting global best practices such as the Livestock Emergency Guidelines and Standards (LEGS) and stresses the mutual dependence of human and animal welfare, particularly in rural India, where more than 95 percent of the livestock population can be found. However, the plan remains limited to livestock. Companion animals, strays, service animals, and even wildlife receive negligible attention despite their social, emotional, and ecological relevance. Further, the plan lacks a mandate for states and districts to operationalise its suggestions. While it recommends integration with state- and local-level plans, there is no mechanism for enforcement or monitoring. There are also no hazard-wise, region-specific interventions for different animal groups.

- The 2005 Disaster Management Act and its 2024 amendment do not address animals or their welfare. The Prime Minister’s Ten Point Agenda on Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR), introduced in 2016, also does not mention the safety and welfare of animals from disaster risks.

Although data collection systems exist, compliance is poor.

Despite these available plans and policies, implementation remains patchy. Early warning systems have improved but rarely include guidance on safeguarding animals. Community preparedness—especially in rural areas—is minimal, leaving pastoralists and their animals vulnerable.

For instance, during our response to recent floods in Assam’s Barpeta and Dhubri districts, we observed that communities living on the sand dunes along the Brahmaputra river are particularly vulnerable to annual floods and river erosion. These communities rely heavily on animals for their livelihood. However, disaster preparedness measures for animals are nearly non-existent, and each year they suffer the consequences of floods, which only increases their vulnerability. This is the situation in many communities across the country.

Lack of robust data on animal populations and disaster impacts is a significant gap in disaster management. Although data collection systems exist, compliance is poor. Few states maintain comprehensive records of animal losses during disasters, another sign of the undervaluation of animal welfare in disaster planning.

While there are gaps at the policy level, there are certain approaches that nonprofits—including those working in disaster management or with rural or pastoral communities living in disaster-prone areas—can take in order to minimise the impact on the ground.

Community-based solutions: The way forward

Humane World for Animals has been working on disaster response in India since 2013. Initially, we focused on direct response and relief, providing emergency rescue, food, and medical care to thousands of animals impacted by floods, cyclones, and other hazards. Over time, our work has expanded to include preparedness, capacity building, and policy advocacy, and we have pivoted towards disaster risk reduction. According to the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, every dollar invested in risk reduction and prevention can save up to USD 15 in post-disaster response and recovery. Therefore, since 2021, community-based disaster risk reduction (CBDRR) has been a major part of our efforts. Unlike traditional top-down approaches, CBDRR is bottom-up, recognising that local communities are the first to experience the impacts of disasters and often possess valuable knowledge and the skills needed to manage them.

Based on our experience, here’s how nonprofits can work with communities on disaster preparedness, response, and recovery:

1. Ensuring that communities can perceive early warning signs

Early warning and risk perception mean that timely, localised alerts reach the people who need them the most. In many communities, we found that women, typically the primary caregivers for animals, were the last to receive warnings or misunderstood them. This was largely due to lower literacy rates, limited access to mobile phones, and low engagement with conventional alert mechanisms among women.

While early warning systems are a work in progress, information, education, and communication (IEC) materials help us inform communities through various means, such as local radio channels, community murals, and poster dissemination in vernacular languages. This is done so that the community knows what to look out for. We also boost our materials via social media. We have also identified potential temporary shelter locations for animals when an evacuation message is issued.

We plan to set up safe evacuation routes with signboards across the district and train communities on how to use it. Standardising how warnings are understood, especially in isolated hamlets, remains a major area of concern. There is still much work to be done to ensure equal access to life-saving information. To mitigate some of this, we’re developing an early warning tool using AI so that each household and their animals can be categorised based on their hazard exposure and provided adequate early warning and preparedness advice.

2. Encouraging community members to prepare emergency kits

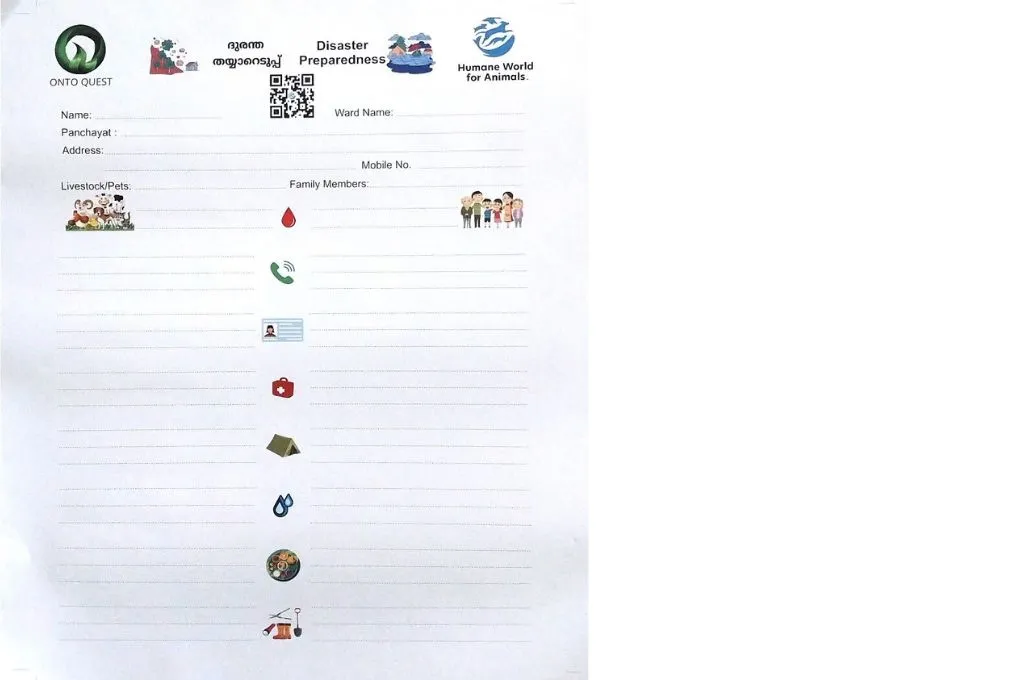

Our advocacy for emergency kits began with children through school-based disaster management training programmes. We created dual-sided checklists, with one side enumerating family needs and the other listing animal essentials, and asked students to complete these at home. Once these were filled out, students were encouraged to paste them in a visible location. IEC materials also helped us reach a wider audience.

3. Carrying out spatial risk assessments

Although it may sound technical, a spatial risk assessment can be made engaging through a participatory approach. Community-based spatial risk assessment involves residents mapping hazards and safe zones using their knowledge. This strengthens disaster preparedness by identifying vulnerable areas, guiding evacuation plans, and ensuring inclusive planning, especially for animals and other vulnerable groups in high-risk regions. What matters the most is that people’s spatial understanding of their own areas elevates risk perception to a whole new level.

Early education shapes long-term resilience.

Our training sessions include an activity called ‘Million Pixels Game’. Large maps of local panchayats are cut into ward-specific segments and distributed to participants, who then identify familiar features such as rivers, post offices, and flood-prone zones.

As they map historical flood zones and locate potential safe areas for animals, communities begin to visualise their vulnerability and take ownership of solutions. In one instance, a playground identified in Noolpuzha panchayat in Wayanad district became a designated safe zone for animals, despite lacking formal infrastructure.

We plan to expand these efforts by installing permanent evacuation maps and past flood-level indicators in public spaces. Through collaboration with Kerala’s Local Self Governance Department (LSGD), we have been able to acquire accurate local maps. This information is further shared with the concerned District Disaster Management Authority for their reference and use during disasters.

4. Conducting disaster management trainings at schools

Early education shapes long-term resilience. We hold school programmes around experiential learning methods such as storytelling, games, role-plays, and drawing competitions, all centred on the human–animal bond. Our sessions target students aged 13 to 15, helping them internalise core preparedness concepts—risk awareness, safety skills, early warning and response, and animal care—while promoting a culture of safety at home.

Scheduling biannual trainings in schools, which are already filled up with curriculum, has been challenging. Now we are in the process of developing a module for teachers along with a textbook for students to learn and practise at their own pace. Even one period per month dedicated to disaster preparedness can lead to bigger changes.

Using local communities’ knowledge, we are in the process of preparing a panchayat-level disaster management plan. This will add an official dimension to our efforts in Wayanad thus far and result in a template that can be used nationally.

Implementing community-level training programmes for animal disaster preparedness requires collaboration, innovation, and sustained effort. Policymakers, civil society, and local communities must work together to bridge the existing gaps and build a more inclusive and robust disaster management system. The well-being of animals is inseparably tied to the welfare of the families who depend on them, and safeguarding one means securing the other.

—

Know more

- Read Sphere India’s Handbook for Management of Animals in Disasters & Emergencies.

- Learn more about the role of companion animals in disaster evacuation.

- Learn what community-led climate planning looks like.