As of 2024, WhatsApp has more than 850 million users in India and is the country’s most popular communication app. Although digital access in India is highly inequitable and is divided along caste, class, and gender lines, WhatsApp is present nearly everywhere, even in rural areas. It is a popular, free, and easy-to-use messaging app, with functionality for voice and video messages—all of which makes it a rather useful tool for the social sector, especially in a post-COVID-19 world. One way the sector can leverage it is through automated interactive messaging, or chatbots.

The Maharashtra government, for instance, is collaborating with Meta on a WhatsApp chatbot to provide citizen certificates, whereas the Punjab government has launched a chatbot that allows citizens to lodge corruption-related complaints. Nonprofits and civil society organisations (CSOs) are also using chatbots to scale their reach and impact while connecting with and engaging the communities they serve in a new way.

In this article, we explore how WhatsApp-based chatbots are currently being used by Indian nonprofits. Additionally, the article can help nonprofits that are unfamiliar with or toying with the idea of incorporating chatbots to gain a deeper understanding of their uses and limitations. For this, we spoke with two organisations that have been using WhatsApp chatbots in markedly different contexts:

- Civis, a nonprofit platform that aggregates laws by inviting public consultations and then inviting citizens, including laypersons, to participate in the lawmaking process.

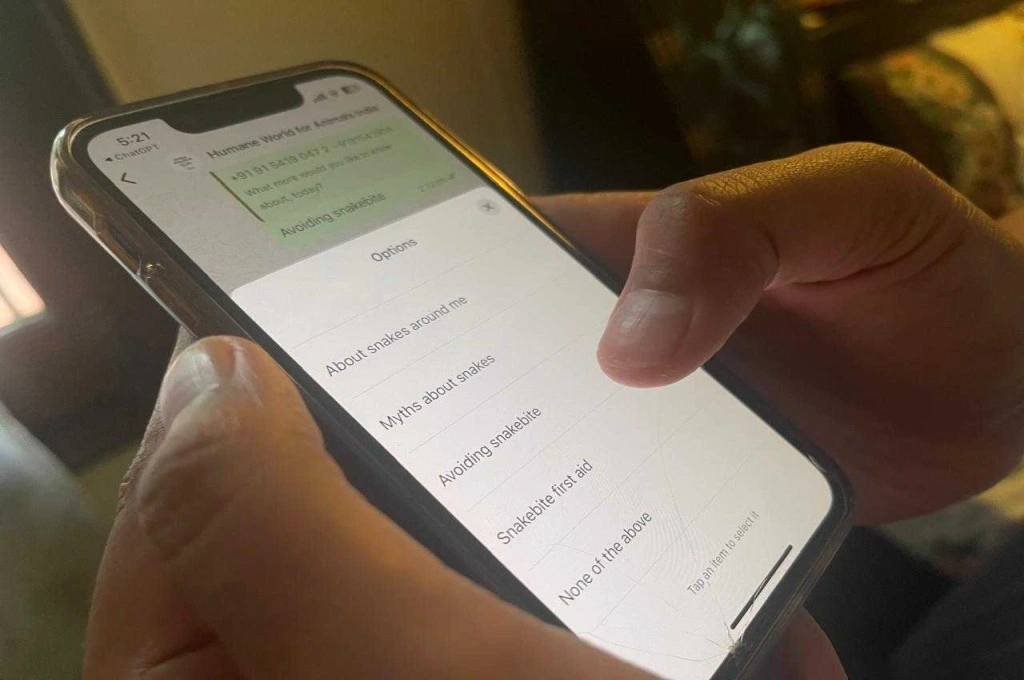

- Humane World for Animals, which works on human–elephant conflict in India, and collaborates with The Liana Trust to address human–snake conflict.

We asked these organisations, both of which employ Glific—an open-source, WhatsApp-based platform—about the rationale behind adopting chatbots, what this process looked like, and the impact this shift has had on scale and engagement. Here is what we learned.

What WhatsApp chatbots can do

Encouraging people to read and engage with policy sits at the core of Civis’s work. Initially, they built a web platform where people could log in, browse policies, and submit their feedback. However, the organisation quickly realised that this model introduced significant friction at every step. Atharva Joshi, senior product manager at Civis, explains, “Signing up, navigating the portal, discovering consultations—all of this required heavy investment in SEO and advertising just to ensure visibility. In addition, the policy cycle itself can take 18 months to three years. People might respond in January 2025 but not see any visible change until 2026 or later.” All of this meant that citizens were not engaging with policy in a meaningful or sustained way.

Civis turned towards WhatsApp chatbots to improve both the nature as well as the scale of engagement. Atharva elaborates, “In 2021, we were onboarded to Glific to explore whether WhatsApp could be a lower-friction channel. The goal was to pilot whether we could replicate our platform’s core functions through WhatsApp,” which people already use and are familiar with.

Four years into using chatbots connected with different themes (such as environment and financial regulations), Civis has seen a qualitative and quantitative shift. Sharing the example of a solid waste management (SWM) consultation held recently by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), Atharva notes that approximately 2,500 people engaged with the consultation through the chatbot. He adds, “Some policies and laws, such as the Budget and its implication on income tax rates, tend to get higher responses. But there’s a general increase in the time that people spend on the bot and the quality of the interaction.” Civis has managed to build a small but consistent audience for even more obscure or technical policies like SEBI regulations. This also means higher repeat engagement.

The biggest and quickest change has been in engagement.

For Humane World, the chief reason for WhatsApp chatbot adoption was to experiment with improving outreach in a cost-effective manner, as well as to ascertain that people were getting accurate information about snakebites. Much of Humane World’s work involves conducting outreach and awareness sessions around snakebite prevention and mitigation with community members directly. Noting that there is an abundance of advice on snakebites and that it can be difficult to distinguish useful information from misinformation, Sumanth Bindhumadhav, director of wildlife protection at Humane World India, says, “Outreach is the single most important part of what we do, but in-person outreach is also incredibly difficult. It is challenging to get a multitude of stakeholders, including community members, together in a room and disseminate information to them.”

Moreover, to make sure that people don’t lose out on a day of work, these sessions are conducted on Sundays, and that comes with its own challenges. “People don’t always want to learn about snakebite prevention on a Sunday. We count on the people present to relay information to others. Given the extensive folklore around snakes and information being diluted at every step of the way, it wasn’t ideal to rely on in-person sessions alone to get the information across.” To provide concise and accurate information to a greater number of people, Humane World decided to add chatbots to their existing in-person efforts.

Humane World has been using a chatbot since 2024. During this time, the biggest and quickest change has been in engagement. Sumanth shares, “In one year, we’ve had approximately 4,500 users. Through only in-person engagement, it would have taken us two or even three years to reach this number.” The organisation has also observed that users ask the bot a wide range of questions. “We initially thought users would be most interested in the myths and facts about snakes (such as snakes drinking milk), given how there is widespread misinformation. But surprisingly, what users seek the most is information on snakebite first aid. This has been really encouraging. It tells us that people are keen to learn how to respond to snakebites, which is a more urgent and life-saving issue.”

The user base is made up almost entirely of community members.

Chatbots can also be useful for organisations that regularly work with communities on the ground but are unable to gauge how many people their work is actually reaching, which can incidentally also make reporting difficult. Sumanth says, “Trackability was a challenge for us. During in-person sessions, we knew how many people were in the room, but we had no visibility on how the information was being shared further or what people were actually taking away. It made impact assessment and follow-up almost impossible.”

Using WhatsApp chatbots also opens up other possibilities. Users of the Humane World chatbot can access it in two languages, English and Kannada. In Civis’s case, users can find policy documents, draft laws, and other materials in English as well as relevant regional languages. “Users have responded to policy consultations in the way that works best for them—through texts, voice messages, or even photos of handwritten responses,” Atharva adds. The high penetration of WhatsApp in India has meant that Civis has received policy responses from 782 out of India’s 788 districts. Humane World has similarly seen high usage among rural communities, at whom their chatbot was primarily aimed. “Aside from a few bureaucrats who’ve used it to understand the use case, the user base is made up almost entirely of community members.” In fact, Sumanth shares, they had initially underestimated people’s tech familiarity, especially around things like scanning QR codes, but people were quite comfortable with scanning and using the chatbot.

Organisational work dictates chatbot efficiency

As with any technology, WhatsApp chatbots are not a panacea. While there are several use cases across various sectors and thematic areas—involving parents in children’s education, sharing social–emotional learning (SEL) resources with teachers, disseminating knowledge to tackle malnutrition—WhatsApp chatbots work best when organisations have clarity about what they want to accomplish through the chatbot while being cognisant of its limitations.

1. Use chatbots to complement, and not replace, other efforts

Notably, both Civis and Humane World are using chatbots to complement their existing work. Sumanth shares, “Nothing replaces the power of in-person interaction, so we use the chatbot to supplement our outreach work.” Civis also continues to use the platform, besides partnering directly with the government to facilitate participative policymaking. Atharva points out that when the chatbot is unable to answer a query, a human steps in. This also becomes necessary when a user asks something that breaks the chatbot’s pre-programmed flow.

2. Chatbots may not be able to satisfy all your data and reporting requirements

Organisations are trying to find a workaround for other gaps in data that are required for strategising or reporting. For example, given WhatsApp’s privacy conditions, chatbots cannot be used to determine user identity or demographics. For Civis, this means not knowing details such as the age and gender of those responding to the consultations. Atharva explains, “We know that our user base comes from 782 out of the 788 districts in India (this means there is at least one user in each of these districts), but other details are not available.”

For Humane World, this means not knowing the true scale of information dissemination. According to Sumanth, for each chatbot user there are likely more users who are getting the information. “For example, if I am using the chatbot to learn about snakebites, I am probably sharing the information it gives me with my family as well. This makes the actual reach perhaps 3–4x of what we are seeing.” Given that trackability was a major reason for Humane World to adopt the chatbot, the organisation is actively trying to figure out ways to determine true reach.

3. One size does not fit all

WhatsApp chatbots ensure that information is readily available for reference whenever a community member or user requires it. To improve the quality of this information, Civis decided to integrate large language models (LLMs) into their chatbots so that the user not only has information on the policy that they are responding to but also has access to background information for context. Feeding and verifying such information and LLM responses has been resource-intensive for the organisation, but it has ultimately paid off. According to Atharva, “The typical policy response before the integration of the LLM was 10–15. This has increased to 30–35 responses.” That’s a 2.5–3x increase.

“For Humane World,” Sumanth shares, “the focus is on presenting information on snake identification, preventing snakebite, and first aid—all of which can be the difference between life and death. But this is also why we haven’t integrated LLMs into our chatbots, because we wanted to maintain strict quality control over it.”

Organisations can, in fact, use several tech tools in combination to meet their goals, but programmatic clarity should precede tech adoption.

—

Know more

- Explore more case studies on the Glific website.

- Read this article to learn what to keep in mind as you experiment with WhatsApp chatbots.

Do more

- Reach out to Glific to learn more about how a WhatsApp chatbot can support your work.