For lakhs of people in India, access to food subsidies has become increasingly insecure—primarily due to discrepancies in the mandatory electronic Know Your Customer (e-KYC) verification of ration cards. Several reports have emerged of individuals being denied access to entitlements under the Public Distribution System (PDS), or of state governments announcing the mass deletion of ration cards.

In May 2025, as part of a study conducted by Libtech—a group of engineers, social scientists, and policy researchers leveraging technology to improve public service delivery—we spoke to migrant workers from Latehar, Jharkhand, who were under strain over the fate of their ration entitlements.

Among these workers was Pankaj Singh,* a 25-year-old construction worker in Gujarat, who could not find a fair price shop near his workplace to complete the e-KYC process. In Mumbai, 40-year-old Santanu Singh,* a painter, somehow managed to reach the fair price shop dealer close to his place of work for the e-KYC, only to be turned away and asked to get it done at the one in his village in Jharkhand, which is listed as the permanent address on his ration card. Meanwhile, although Prachi Kumari,* a construction worker in her 30s working in Tripura, was able to complete her e-KYC at her nearest fair price shop, it never reflected against her name in the state’s PDS portal, which has details of ration card holders with their e-KYC status.

These stories reflect what is becoming the norm for socio-economically vulnerable people across the country: bearing the brunt of an abrupt and opaque change in the systems through which they exercise their right to food.

On March 25, 2025, the union Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution (MoCAFP) issued a notice to all states and union territories to complete the e-KYC of all ration card holders eligible for PDS under the National Food Security Act (NFSA) by the end of April 2025. The letter noted that while the e-KYC process for all those covered under the act has been ongoing, failure to achieve 100 percent completion by the designated date may result in the withholding of subsidies and curtailment of food grain allocation.

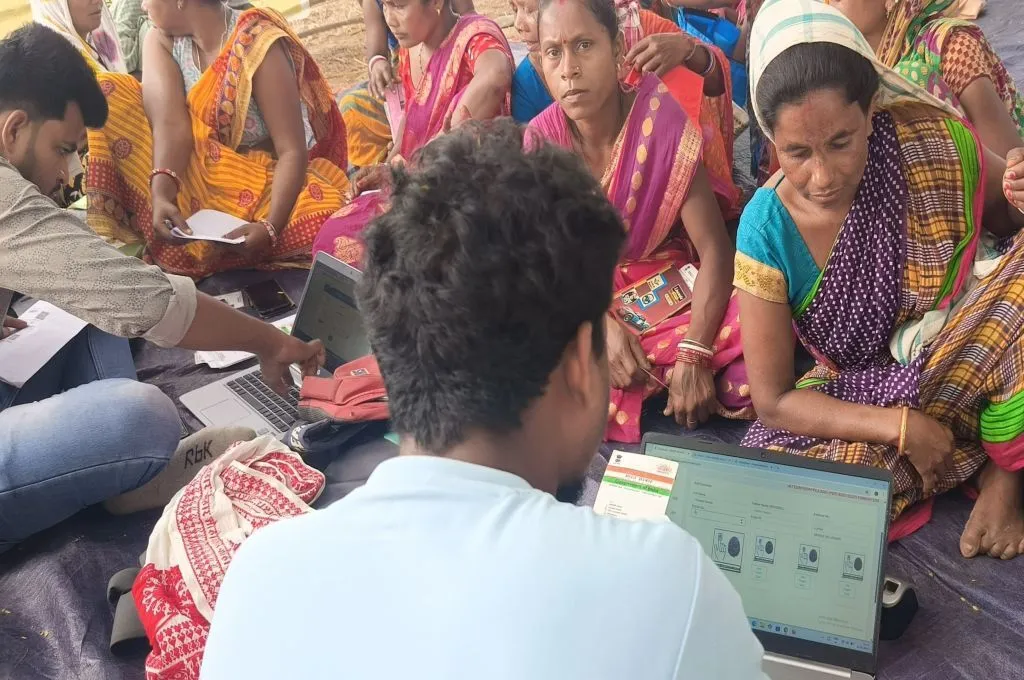

E-KYC verification involves confirming the identity of a person through biometric authentication, followed by matching the demographic data on their Aadhaar card with their ration card. The process requires all members listed on a ration card to link it to their individual Aadhaar numbers, and to undergo biometric or IRIS authentication through electronic point-of-sale (e-POS) machines at a fair price shop. However, activists and observers have reported that marginalised communities have encountered major disruptions in this process.

Evolution of the e-KYC process

The first significant communication from the MoCAFP on e-KYC was on August 20, 2019. It outlined the purpose of the verification and suggested procedures for achieving full coverage. In March 2023, another advisory clarified that Aadhaar numbers had been seeded (or linked) for 95 percent of ration card holders, while highlighting that validation remained a concern.

According to the ministry, it was primarily one member from each ration card-holding family who would undergo biometric authentication to collect ration from the fair price shop. As such, since other family members had not authenticated their identity, there was a chance of duplicate or ineligible individuals being included in the system. As a result, the ministry stated that the government must ensure 100 percent authentication to confirm that seeded Aadhaar numbers belonged to those listed on the ration card, and that this was only possible through Aadhaar-based biometric authentication. Another letter was issued in June 2024, directing 100 percent compliance with the e-KYC process of all ration card holders across the country.

According to a response in the Parliament on March 25, 2025, 100 percent of ration cards had been digitised, 99.3 percent had been seeded, and 99.6 percent of fair price shops had an e-POS installed. E-KYC had been completed for 75.69 percent of ration card holders across the country, with Karnataka leading at 98.2 percent completion. Delhi had covered the lowest percentage of its eligible population, at just 6.6 percent.

Odisha was among the first states to start the e-KYC drive as early as August 2024, supposedly to weed out more than 50 lakh fake ration cards and streamline the system. Since then, the deadline has been pushed back multiple times, while the government has ‘temporarily suspended’ rice distribution for over 20 lakh eligible individuals, citing non-compliance with e-KYC. Conflicting reports have emerged over the issuance of new ration cards despite pending e-KYC verification for existing holders.

Aadhaar-linked authentication failures cause exclusion

Biometric authentication through Aadhaar often fails for people such as construction workers, domestic workers, and farmers, whose fingerprints are worn out from years of strenuous manual labour. Elderly people and children, whose biometric information is either unstable or underdeveloped, face similar barriers, especially since eligibility for food access depends on up-to-date data.

When combined with patchy internet and bug-riddled tech, data verification becomes a bottleneck. Information gets trapped in limbo between e-POS machines, ration databases, and the Aadhaar system—locking out India’s most vulnerable citizens from the food system meant to protect them.

During field work in Latehar, we also spoke to Gangadhar,* a 45-year-old farmer, who discovered that his Aadhaar number was linked to his wife’s ration card without his knowledge. As a result, when he went for his e-KYC verification, the fair price shop dealer turned him away, stating that his wife’s name was appearing twice on the ration card. Multiple such cases of errors in the seeding of Aadhaar with ration cards have been reported across the country. In many instances, there have been threats of outright deletion of such ration cards without any further investigation or grievance redressal, leaving people like Gangadhar without any relief.

Since its entry into PDS over a decade ago, irregularities in Aadhaar-linking have had devastating consequences. In 2017, the Right to Food Campaign (RTFC) documented more than 20 starvation deaths where Aadhaar-related issues had blocked PDS access. The State of Aadhaar Report (2020) also found that more than 30 percent of people who faced authentication failures at PDS outlets did not receive their rations at all.

Authentication failures due to poor network in remote rural areas

Unreliable network connectivity has long plagued the implementation of e-KYC in public provisioning systems, particularly in rural and remote areas. In Pratapgarh’s tribal regions, for instance, ASHA workers reported that poor internet access hindered the completion of e-KYC for persons entitled to Ayushman Bharat. In Odisha, where network connectivity issues disrupt even regular ration distribution, the government had to extend the e-KYC deadline as ration card holders could not update their details in 341 ration shops.

Systemic outages in Aadhaar authentication services have been documented for several years. In 2023, the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) acknowledged more than 54 hours of service downtime due to issues such as OTP delays and server fluctuations, affecting the reliability of biometric authentication. But these have not been just recent events. A 2017 report found ‘complexities and problems’ in the Aadhaar-based Biometric Authentication (ABBA) system in PDS mechanisms in Hyderabad, with 66 percent of households surveyed reporting glitches in at least one of the system’s five technological components.

Migrant workers are often away from their registered address

E-KYC is often linked to the Aadhaar, which is tied to a permanent address. Due to this, workers who migrate frequently are unable to access their entitlements as they often lack proper documentation or the ability to authenticate their identity using e-KYC when they move from one location to another. This leads to barriers in accessing crucial PDS subsidies.

In June 2024, MoCAFP issued an order stating that migrant workers could visit any fair price shop near their place of work to initiate their e-KYC through an e-POS machine. The data would be transferred to the worker’s home state, and verification would only be confirmed after approval by the concerned state authorities. Despite this, a lack of awareness about this provision and instances of outright and arbitrary denial of verification by fair price shop dealers has forced many migrants to return to their home states to complete e-KYC. Moreover, dealers reportedly also extort hefty sums from migrants under the guise of updating their e-KYC.

Fearing that his name might get deleted from the ration card, Girija Nayak,* a migrant security guard working in Bangalore, rushed back to his village in Nabarangpur, Odisha, to get his e-KYC done. Having been hired on contract as a casual worker, he told us he was scared he had put his job in jeopardy by taking leave to travel.

In light of the challenges faced by people who could not reach their nearest e-POS, MoCAFP launched the mobile Mera eKYC app. It uses Aadhaar-based face authentication technology and one-time password (OTP) verification to complete e-KYC. While the app is useful, an ongoing field study by Libtech has found that only a limited number of ration card holders—those who have smartphones and internet connectivity, and importantly, whose phone number is linked with their Aadhaar card—have been able to use it.

Access to clear information on procedures is limited

Despite a concerted push for mandatory e-KYC for PDS entitlements, there is insufficient information about its necessity, timelines, and the consequences of non-compliance. This lack of transparency has led to confusion and distress among ration card holders, many of whom are unaware of the steps required to complete the e-KYC process or the implications of failing to do so.

The responsibility of informing those eligible about e-KYC requirements has frequently fallen on fair price shop dealers, who may not have the necessary training or resources to provide accurate guidance. In addition to this, right to food campaigners have noted that ration shopkeepers have been vested with the responsibility to conduct e-KYC verification, effectively giving them power over issuing or cancelling ration cards, which is the mandate of the Food Department.

Dealers themselves remain confused about this delegation of responsibility. In December 2024, the Delhi Sarkari Ration Dealers Sangh filed a petition in the Delhi High Court against this ‘forced labour’. The application categorically emphasised that the ration dealers were private parties who had been licensed only to receive ration from state authorities and to distribute it to the ration card holders assigned to their shops. As per the licensing terms, ration dealers are not responsible for verification and re-authentication of eligible individuals. This is primarily the responsibility of the officers of the respondent Department of Food and Public Distribution and the Vigilance Committees formed in each state under the NFSA.

In June, the Gujarat Fair Price Shops and Kerosene License Holders Association also began a protest in the state calling the new requirement for e-KYC ‘unjust and impractical’. The action put PDS services on halt, leaving thousands of people in the lurch.

Violation of the right to food

As unclear procedures and authentication failures continue to pose obstacles to people’s access to food, activists and campaigns such as the RTFC have urged the government to immediately halt e-KYC of ration card holders and to instead focus on giving ration cards to eight crore migrant and informal workers, as directed by the Supreme Court in March 2024. The campaign has also called for the removal of exclusionary digital measures such as e-KYC and Aadhaar linking from PDS altogether.

When subsidies are subject to biometric authentication, uninterrupted network connectivity, and bureaucratic compliance, the right to food becomes a conditional privilege. Such a techno-solutionist approach, which disregards structural exclusions, lived realities, and the failures of public infrastructure, undermines the NFSA’s core premise—that of a ‘rights-based approach’ to food security.

While cloaked in the language of efficiency and transparency, the mandatory e-KYC regime has effectively weaponised digital infrastructure to exclude people on the basis of narrow digital identifiers. In doing so, the state abdicates its constitutional duty to ensure food security. The right to food cannot and in fact must not hinge on digital legibility. To continue down this path is to sanction systemic starvation by design.

*Names changed to maintain confidentiality.

—

Know more

- Read more about the impact of the e-KYC verification process on migrant workers.

- Understand the gaps in the One Nation, One Ration card scheme.

- Learn about the gaps in PDS coverage and the prevalence of undernutrition in India.