How many different ways do you use a T-shirt before deciding that it’s time to throw it out? Maybe it doesn’t fit as well anymore so it becomes a hand-me-down. If it is worn out or torn, it might get repurposed as a mop or dusting cloth. Ultimately, you dispose of it in the garbage—but where does this waste go?

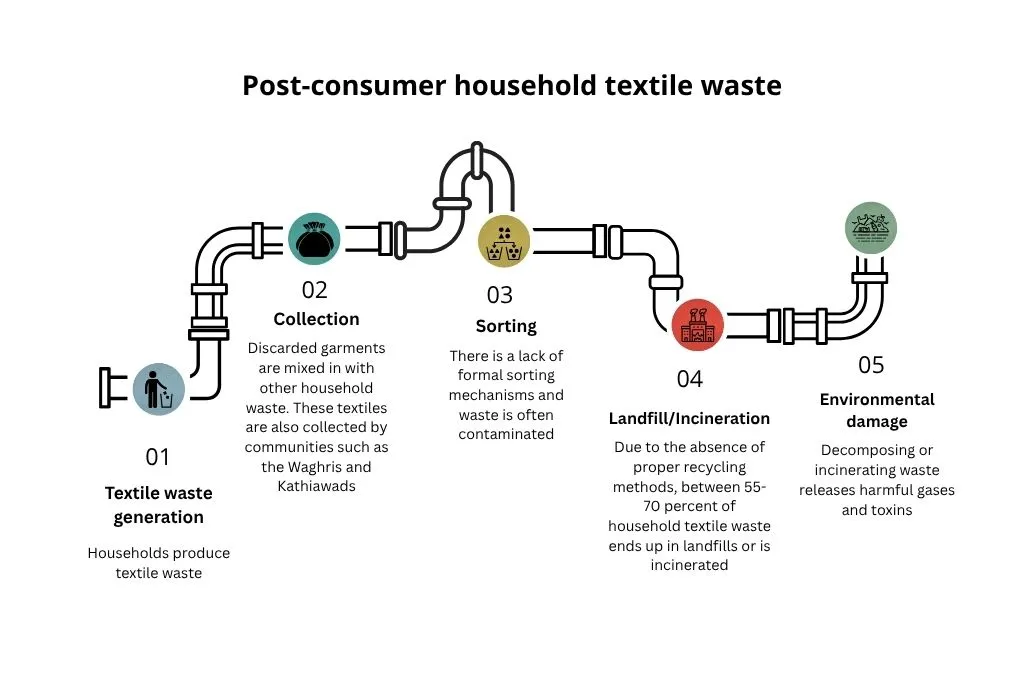

Textile waste is the third-largest contributor to municipal solid waste in India. Each year, 7.8 million tonnes of this waste is accumulated across the country. Less than half of this waste is repaired, reused, or put through high-grade recycling. Discarded textiles from households—broadly known as post-consumer waste—form the bulk of textile waste India. Due to a lack of proper mechanisms for collection, sorting, and processing, estimates suggest that 55–70 percent of post-consumer textiles disposed by urban households are either incinerated or slowly decompose in open-air landfills, releasing toxic gases and polluting chemicals.

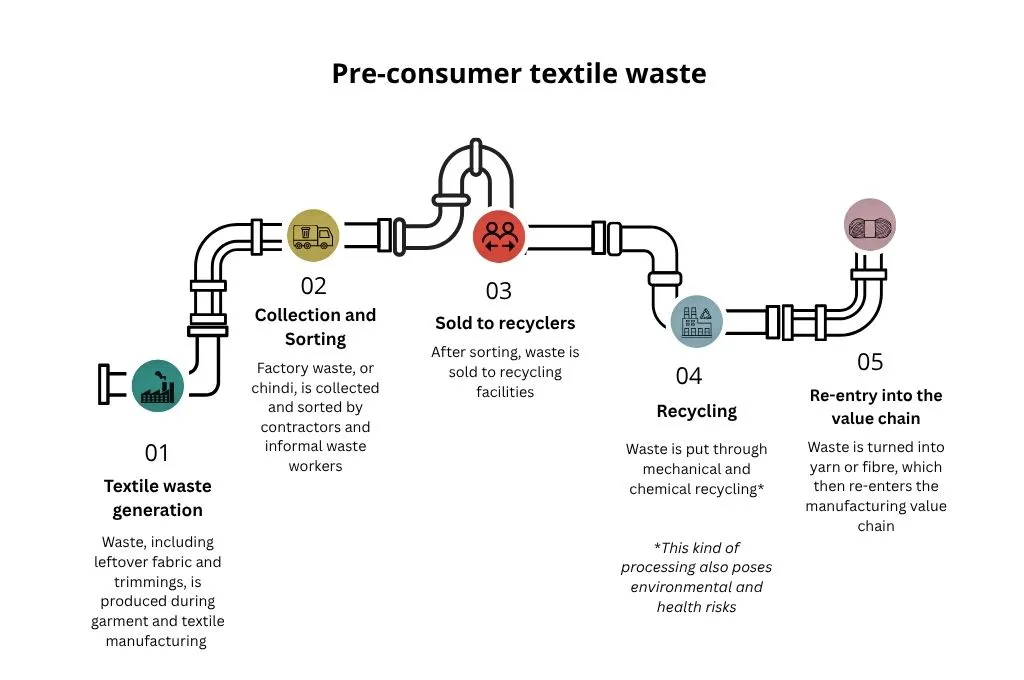

What is discarded from households is one part of the story. The process of textile production itself generates significant amounts of waste; this is known as pre-consumer textile waste. Unlike post-consumer textile waste, there exists an extensive, albeit largely informal, chain for the collection, sorting, and recycling of pre-consumer textile waste in India.

More waste, more problems

Fast fashion has driven a surge in consumption in India’s urban metropolises. This has led to an increase in waste generation at both the production and the disposal level, making its environmental and social costs harder to ignore. Between 2019 and 2023, textile waste in India alone increased from 6 million tonnes to 7.8 million tonnes—a 30 percent hike within four years. That’s enough textile waste to make a T-shirt for every human on earth, ten times over.

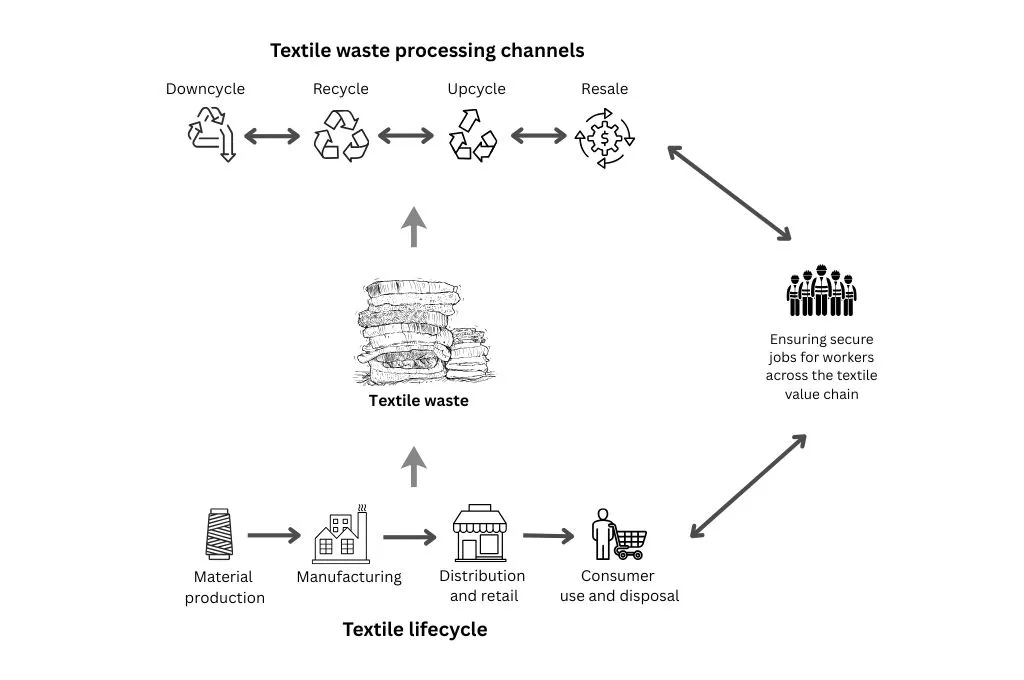

In recent years, there have been efforts to solve the growing textile waste problem through circularity, which involves mechanisms to recycle and reuse discarded materials to reduce waste. To learn more about the challenges of collecting and processing this waste, we spoke to organisations that are implementing circularity in places where post-consumer textile waste management systems are still largely non-existent. Here’s what they found.

1. Households don’t know how, or where, to dispose of textiles

Waste collection from households is highly uneven in India, varying across urban and rural geographies, and even within cities.

Household textile waste is disposed of through a variety of means. Communities such as the Waghris and Kathiawads go from household-to-household and barter old clothes in exchange for utensils or money, and then sell these clothes to retailers or in local second-hand clothing markets directly. There are also other steps that people take to dispose of garments they no longer need, including as donations to nonprofits and collection drives, or to brands that have programmes to take back discarded clothes.

More commonly, people pass on old garments to domestic workers. However, when these clothes are damaged, they are unusable for domestic workers, and end up accumulating as waste in their households, where access to proper disposal may be more difficult. “More often than not, domestic workers also feel unable to refuse hand-me-downs from their employers, even when the items are of little use, and so they take them, only for many of these garments to eventually make their way to landfills,” notes Zibi Jamal from Saamuhika Shakti, a network of 12 organisations working with informal waste pickers in Bengaluru on issues such as livelihoods, gender, and health.

What is not given away is usually mixed in and thrown out along with other household waste, and it is then collected by municipal or informal waste pickers. In Bengaluru, household waste is collected and brought to dry waste collection centres (DWCCs). Be it from landfills or DWCCs, waste pickers have tried to recover and reuse textile waste. However, a lack of formal collection and sorting mechanisms and high levels of contamination have made this process extremely difficult.

Hasiru Dala, a Saamuhika Shakti partner, has been working on textile waste management with workers at these centres for the past five years.

“Earlier, when textile waste would come into the DWCC with the household dry waste, we did not know what to do with it. We would give to cement factories for incineration. However, once these factories stopped taking these textiles, they started piling up in the collection centre. We started to think about whether these textiles could be turned into a source of livelihood, while also reducing the amount of waste,” says Mouna Balakrishana, a project coordinator at Hasiru Dala.

“We realised that approximately 85 percent of the textile waste we were receiving in the centres was recyclable if disposed in the right way. If it was mixed in or contaminated by other kinds of dry waste, less than 1 percent would be salvageable. We also focused on post-consumer textile waste because of two reasons: existing recyclers want to work with pre-consumer waste, and post-consumer waste is a major challenge because we use these textiles 24×7.”

2. Recycling post-consumer textile waste is not prioritised

In India, 51 percent of total textile waste is post-consumer. Despite this, existing recycling facilities tend to either prefer pre-consumer waste or imported post-consumer waste. Scraps and trimmings left over from manufacturing (pre-consumer waste) tend to be more uniform in terms of material and composition—making them easier to segregate and process. In Tiruppur, which is a major recycling hub in southern India, recyclers prefer to work with pre-consumer cotton waste.

Discarded garments or household textiles, on the other hand, are often composed of mixed or blended fabrics, making sorting more difficult. Moreover, they also tend to be damaged or otherwise contaminated by use. Importantly, while facilities in Panipat, a major recycling hub in northern India, do work with post-consumer waste, they primarily rely on imported waste that comes in from countries in the Global North.

As a result, in the absence of proper disposal and re-processing channels, the majority of domestic post-consumer waste in India still ends up in landfills or incinerators.

Processing post-consumer waste: What is needed

In 2022, Intellecap’s Circular Apparel Innovation Factory (CAIF) joined Saamuhika Shakti to implement Closing the Loop on Textile Waste (CTL)—its circular textile waste management initiative—in partnership with Hasiru Dala. The CTL initiative has been implemented in 11 other cities across India, in collaboration with different on-ground partners such as Green Worms in Kerala.

Establishing systems for collection and sorting

CAIF and Hasiru Dala, which was the implementation partner in Bengaluru, worked with 16 DWCCs in the city and identified two key components of the waste management process.

Collection: To avoid contamination from other household waste, textile waste has to be collected separately. Bengaluru already has a mandatory ‘two bins, one bag’ system to segregate waste at the source. Waste pickers now take textile waste separately during the daily door-to-door collection, collecting an average of 1,500 kg per ward every month, according to internal project monitoring data.

Sorting: After collection, textile waste needs to be sorted. In the DWCCs that Hasiru Dala works with, a primary level of sorting is done once the waste comes in, following which it is packed and sent to a Textile Recovery Facility (TRF) which became operational in 2024. Secondary and tertiary levels of sorting take place here, and then the waste is sent to different vendors.

After sorting, waste can be diverted into the following channels based on its condition:

- Re-selling through thrifting, second-hand markets, or re-sale shops.

- Recycling, where waste is turned into yarn or fibre.

- Upcycling, where existing materials or garments are repaired and re-designed in a way that enhances their value and creates new products that can be used and sold. For example, patchwork quilts or jackets are made by combining different fabric and textures.

- Downcycling, through which waste is repurposed to create products of a lower quality, such as cleaning mops, floor mats, and stuffing for mattresses.

- Rejects, or unusable waste that is sent to waste-to-energy plants.

Finding a viable market to channel waste

While re-selling and upcycling continue to account for a marginal share of the accumulated textile waste, recycling and downcycling hold the bulk, with materials sold per kg instead of per piece.

“Waste is a logistics business, so one has to find markets that are ideally close by. It is possible to locate downcyclers in local areas, but recycling facilities continue to be concentrated in clusters such as Panipat and Tiruppur,” says Somatish Banerji, a partner at CAIF.

The high cost of shipping post-consumer waste over long distances to Panipat, especially from southern cities such as Bengaluru, is economically unviable, making local alternatives more important. Meanwhile, some waste management companies in other locations are also finding ways to add value to waste. For instance, in Goa and Aurangabad, downcycled textile waste is being used to manufacture industrial cleaning wipes, which are otherwise made from brand-new materials. Moreover, recent innovations have also made it possible to reuse downcycled materials such as felt in sectors such as automotives and apparel production. As a result, even if downcycling is not the ideal use for textile waste, it has become a more viable alternative for the time being.

At the same time, the textile and apparel industry must reduce its dependence on unused or virgin materials. A key pathway to achieving this is for brands, manufacturers, and recyclers to collaborate and develop new, diversified products using discarded post-consumer waste.

Securing buy-in, from consumers to recyclers

From convincing households to clean and separate daily waste to larger efforts at aggregating textile waste, behavioural change and awareness play an important role. For Hasiru Dala and CAIF, this has entailed door-to-door awareness generation, which means educating people during daily waste collection, putting up informational posters and flyers, and appointing one supervisor in each ward to carry out campaigns informing people about proper disposal.

This also involves specific messaging to encourage people to sort and hand over textile waste. “It is important to note that textile waste is not something households generate every day like plastic waste. So, a lot of our messaging focused on what this waste was leading to earlier, how we planned to add value to it, how it would create new skills and jobs and improve livelihoods of waste pickers, and how, through this approach, we ensure such waste does not end up in landfills,” Somatish shares.

“Gradually, you do get buy-in from people. For instance, in Bengaluru, many households now wash textile waste before handing it over. Of course, when you go to a different city, the scenario is different, so you do need to adjust the language and message to fit the context.”

How can household textile waste management be improved?

While circularity is beginning to gain ground in the processing of household textile waste, reducing the environmental impact of waste accumulation in urban areas also requires behavioural change and a reduction in overconsumption. It is also important to note that patterns of consumption and disposal are not uniform and vary depending on factors such as income and location, which dictate purchasing choices along with cultural influences or trends.

At the individual or familial level, then, making more conscious decisions to extend the life of garments, purchasing from sustainable brands in cases where such garments are accessible, and identifying nonprofit organisations or networks to give away clothes to can reduce excess consumption and subsequent waste. Options to purchase upcycled or thrifted clothing have also become easier to find in cities through social media.

When clothes eventually become waste, there must be mechanisms for responsible disposal or channels to divert this waste for re-use. Once collection systems are in place, households can be informed about separating clean textile waste to avoid contamination.

“There is a need to build systemic awareness,” says Zibi. “People must be given information about where their clothes go after disposal, and how and where they can send their waste. This is not about donations or charity—a system has to be put in place so that people can responsibly discard what they no longer have use for.”

For instance, BBC Media Action’s ‘Got Old Clothes?’ campaign in Bengaluru uses business cards to connect people to a WhatsApp chatbot that directs them to their nearest DWCC, where they can dispose of old clothes. The cards themselves are made from upcycled textiles and are stitched by waste pickers who have undergone tailoring training.

It takes more than 200 years for textile waste to decompose in landfills. Not only does untreated waste pollute the environment, its collection and sorting in the absence of proper infrastructure risks the health and livelihoods of informal workers who do the bulk of this processing—whether in recycling facilities or neighbourhood waste collection points.

Circularity, then, is not limited to mitigating the environmental impacts of what we consume and how we dispose of it. Rather, it must centre the rights of informal waste pickers to safe, dignified, and secure livelihoods, and ensure that sustainable innovations in the management and processing of textile waste go hand-in-hand with the principles of equity and justice.

—

Know more

- Read more about the textile waste landscape in India.

- Learn about the traditional upcycling ecosystem of the pheriwalis.

- Understand the risks that textile waste poses to workers and the environment.

Do more

- Reach out to the ‘Got Old Clothes?’ campaign in Bengaluru to learn how you can responsibly dispose of old clothes.