Energy infrastructure projects, particularly thermal power plants, are often championed as engines of progress. However, the reality for the communities living near these projects is often far more complex and fraught with challenges. Energy projects can bring with them a host of challenges: increased pollution, forced displacement, loss of access to common resources, and disruptions to health and livelihoods.

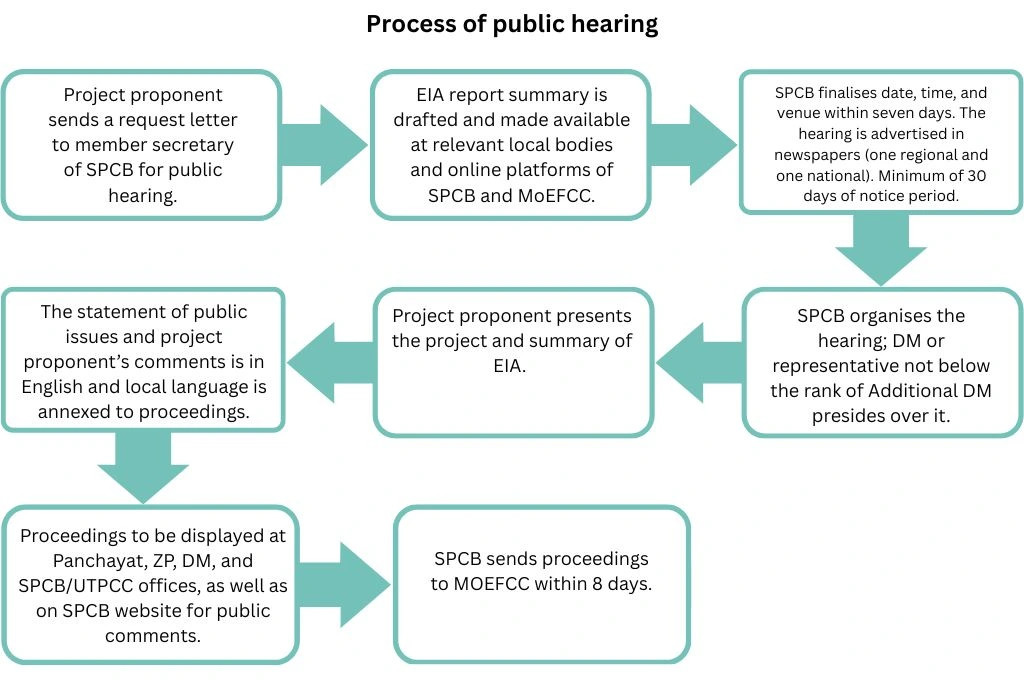

To minimise such impacts and guide more responsible decision-making, India introduced a mandatory regulatory process known as the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) in 1994. The EIA is designed to identify and inform decision-making bodies of a project’s potential impact on human health, natural resources, and man-made resources.

Under EIA, projects are categorised based on the scale and nature of their potential impacts. Category A projects are typically large-scale or environmentally sensitive ones, which require prior environmental clearance from the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEF&CC), based on the recommendations of an Expert Appraisal Committee (EAC). This committee conducts a detailed scrutiny of the Draft EIA—including public hearings, baseline environmental studies, and preparation of an Environmental Management Plan (EMP) for risk mitigation.

A key part of this process is the public hearing. The EIA framework mandates that local stakeholders, especially those within a 10-km radius of the proposed site, be given the opportunity to voice their concerns, offer feedback, or demand safeguards. These hearings are meant to ensure that those most affected are not the last to know, but the first to be heard.

The case

On February 7, 2025, one such public hearing took place in Chhabra, Rajasthan. It was held by the Rajasthan State Pollution Control Board (RSPCB) to discuss the proposed expansion of the Chhabra Thermal Power Plant (CTPP). Operated by the Rajasthan Vidyut Utpadan Nigam Ltd (RVUNL), a state-run power corporation, the expansion would squarely place the project in Category A of the EIA Notification, 2006, requiring prior environmental clearance.

As required by law, RVUNL commissioned an expert agency to prepare the EIA report and submitted it to the RSPCB for public consultation. A panel chaired by the district collector (or an officer holding equivalent rank), with support from the RSPCB, was responsible for conducting and overseeing the public hearing. Following the hearing, the EAC is expected to review the minutes and written submissions, assess how stakeholder concerns have been addressed, and ensure that these inputs are reflected in the decision-making. Before the environmental clearance is provided, the expert appraisal committee must respond to how the objections raised will be addressed by the project proponent.

A research team consisting of one of the authors and their colleague participated in the hearing to submit their written response and witness the process. During the hearing, residents reflected on the initial optimism when the plant was proposed in 2005. The thermal power plant acquired much of the common land and agricultural land from farmers—the economic backbone of the area. They were assured that the project would transform their lives by bringing better roads, improved schools, hospitals, and stable employment for local youth. However, nearly two decades later, the lived reality of the communities is a mixed bag with some benefits and many disappointments.

What community members shared

Monthly environment status reports submitted by RVUNL continuously indicate that air pollution levels, especially sulphur oxide and dust, go beyond safety limits. It was discussed in the public hearing that the plant’s pollution control equipment is frequently under maintenance, which means harmful emissions are released without proper filtering.

Additionally, the CTPP has an ash pond that spreads over 32 hectares, and the plant has struggled to manage dry fly ash, bottom ash, and pond ash. A farmer from Titarkhedi expressed that during the monsoon, the ash pond spills into nearby streams and irrigation channels, which turns them into toxic sludge unfit for consumption and agriculture. One farmer recounted how his opium flowers, a crucial cash crop, wilted prematurely due to ash deposits, leading to devastating financial losses. The once-fertile black soil of the region has turned white due to fly ash deposits and wastewater seepage, increasing the stretch of barren land.

The problem of fly ash extends beyond farms. Heavy vehicles carrying fly ash move near residential areas without proper safety and dust control measures, reducing visibility on roads and contributing to fatal accidents.

Even health concerns have escalated. A local doctor, Chandresh Singh,* reported a sharp rise in respiratory diseases, especially among children and the elderly. Cases of stomach infections were also reported to be on the rise—likely due to wastewater discharge into local water bodies.

Workers and the local communities have been demanding the establishment of a hospital, but this has been stuck in a bureaucratic process for over five years now. “Although some land was allotted for a dispensary, there are no doctors available to provide essential medical services,” reported a local resident.

Additionally, while the plant facilitated educational infrastructure by providing land within its premises for the establishment of a Kendra Vidyalaya school, residents remain concerned about the shortage of school seats for their children. A frustrated parent summed up the issue: “The few seats we have are already filled with the children of plant workers. With this expansion, our kids will be denied those also.”

These testimonies reflect the real and ongoing impacts of the thermal power plant on the region’s people and environment. However, rather than serving as a forum to acknowledge and address these concerns, the public hearing in Chhabra was marked by procedural lapses, lack of transparency, and a deep sense of exclusion.

A case of systemic undermining of the public consultation process

The public hearing for the Chhabra Thermal Power Plant expansion fell short of its intended purpose in multiple ways:

1. Spatial and social exclusion

Despite being a space meant for community voices, the hearing was dominated by elected representatives and influential figures. This was evident from the spatial organisation of the hearing—politically powerful locals and contractors were allocated special seats close to the podium. The majority of speakers were male and affiliated either with the plant or political groups, sidelining community voices.

2. Procedural non-compliance

The EIA process mandates that affected communities be provided with accessible information in advance. But in this case, key documents such as the executive summary of the EIA report were either not available in Hindi, the local language in the area, or not shared widely enough. RSPCB did not publish the summary of the EIA report on its website either even though it is mandated to be published at least 30 days prior to the public hearing. A local leader from Chhabra remarked, “I filed an RTI to access the EIA report a few days ago and I still haven’t received a reply.” Another remarked, “We have been trying to obtain the document but have not succeeded.”

The researchers didn’t confirm at the time if the guidelines for advertising the public hearing were followed by RSPCB. However, this lack of prior disclosure effectively limited the ability of residents to understand the full scope of the project’s environmental and health implications. One of the locals from Motipura (a nearby village) expressed his dissatisfaction with the process, calling it mere formality.

3. Lack of transparency and accountability

Several community members raised concerns around pollution levels, health impacts, and the lack of adequate compensation for land acquisition. However, the non-disclosure of crucial documents—such as emissions data, health impact assessments—and compliance reports severely undermined the ability of participants to question the EIA. The official emissions data from the CTPP frequently exceeded permissible norms. But this data was neither proactively shared with the community nor made accessible through public platforms. In the wake of non-disclosures and barriers to access, the agency of the people in relation to regulators and project proponents was automatically weakened.

4. Dismissal and silencing of concerns

Even during the course of the hearing, the project proponent, RVUNL, stuck to evasive and non-committal answers in response to the issues against the upcoming expansion. When community members raised pervasive issues such as air and water pollution, the project proponent simply responded that it won’t happen in future. As the hearing progressed, officials became increasingly dismissive of questions posed, particularly towards the end. After two hours, the hearing was abruptly curtailed on the grounds it had ‘gone on for too long’, with instructions that any remaining concerns must be submitted in writing to the SDM office within 24 hours. Consequently, the public departed profoundly dissatisfied, as their critical questions remained entirely unaddressed.

As of July 2025, a plant worker and a local stakeholder who made written submissions to the SDM office in February 2025—regarding fly ash, damage to crops, and worker safety—are yet to receive a response.

5. Fear of repercussions

Beyond the issues of transparency and accountability, fear of retributive action was a significant deterrent for workers. A worker shared in confidence that the workers present in the hearing wished to raise concerns, but they were afraid to speak in front of contractors and plant authorities due to possible repercussions.

The only woman who spoke during the hearing, raising the issue of her being unjustly fired from her job at the plant, was asked to calm down and take a seat. Later her questions were met with evasive and inconclusive answers from the authorities.

The way forward: Upholding public hearings in spirit

As is evident from experience of public hearing of CTPP expansion, much needs to be done to uphold the spirit of EIA.

To begin with, procedural compliance should be non-negotiable within an existing policy and regulatory framework, and its enforcement must be of paramount importance. Lapses—such as non-publication of EIA summary on websites of the relevant pollution control board and their access to documents and information at local offices—should not be discarded as minor infringements, and strict accountability must be demanded of erring officials.

In any case, procedural compliance alone is not sufficient for instruments like EIA and public hearings to deliver inclusion and justice. There is a glaring need to address information asymmetry, capacity gaps, and building public trust in democratic processes. Active disclosures of critical information about economic and environmental risks could be critical for communities to provide informed consent and raise concerns. Currently, EIA is conducted by accredited agencies hired by project proponent, which is a direct conflict of interest. This needs to be addressed to make the exercise of EIA transparent and effective.

Lastly, to build public trust in EIA processes and public hearings, local governments, regulators, and civil society must provide targeted education for the inclusion of marginalised voices and identities. The trust-building exercise, however, would be fruitless unless fears of retribution are addressed and the overall process becomes responsive and accountable towards the legitimate concerns of the community members.

As India enters a new era of infrastructure development powered by public and private capital, it is only prudent that we strengthen our foundational processes to deliver long-term sustainable development and benefits for all.

Images courtesy of the authors.

—

Know more

- Understand the EIA process, its history, and evolution.

- Read about a framework to guide India’s renewable energy sector.