READ THIS ARTICLE IN

Pineapples offer a lifeline to traditional saree weavers in Banaras

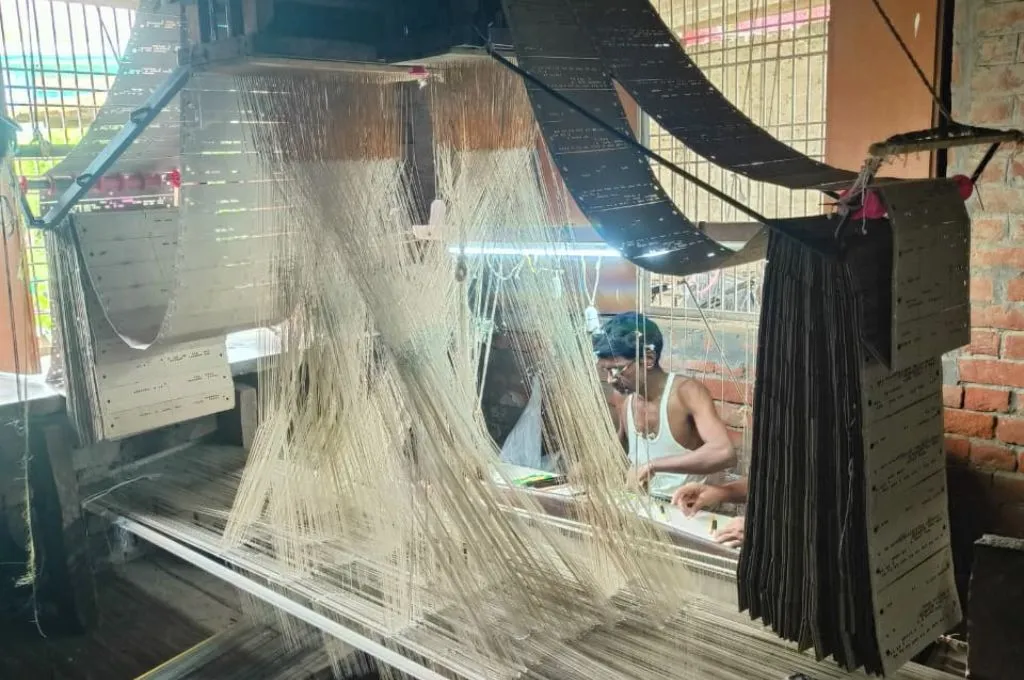

The Banarasi sarees from Varanasi are known for their fine weaves and intricate designs. Approximately 1.2 million people in this region are directly or indirectly associated with the handloom silk industry. It is the primary source of income for the weaver community. However, the industry and its weavers are facing several challenges.

Manoj, a 40-year-old weaver from Chhota Mirzapur village in the neighbouring Mirzapur district, speaks about the drastic shifts they have experienced over the past few decades. “Silk and zari became expensive in the 1970s; in the 1990s, power looms arrived. As a result, by the year 2000, machine-made versions of these sarees began flooding the market, and after 2010, digital marketplaces came up. We had no experience with this new kind of market. Moreover, the legacy we had inherited over the course of generations was nearly wiped out by COVID-19.”

But Manoj stays hopeful. “To save this art, we must be directly connected to the market. Raw materials need to be cheaper, loans must be easier to access, and the GI [geographical indication] tag has to be protected.”

Like Manoj, many weavers feel that it’s becoming increasingly difficult to keep up with the changing times. Samiullah Ansari, a 55-year-old weaver from Ramnagar, Varanasi district, shares, “Earlier, people would look at me with admiration and say, ‘He’s a Banarasi saree craftsman.’ Now they just refer to me as a fabric weaver. Before power looms, handloom saree weavers were highly respected and earned well. The looms have taken away that recognition. Today, there are only 7,000–8,000 looms in Varanasi that still weave Banarasi sarees.”

Due to the uncertainty of livelihoods, many weavers have migrated to cities such as Surat, Mumbai, and Bengaluru. However, efforts are being made to revive the saree industry in Varanasi through new technologies and methods. One such method is the weaving of Banarasi sarees with pineapple fibre, which is more affordable and durable than silk.

Dr Angika Kushwaha, who developed the technique of making thread from pineapple leaves, explains, “During my research in 2019, I found that pineapple grows abundantly in Uttar Pradesh, Assam, and the Northeast region. But after harvesting the fruit, its leaves are left to rot in the fields. In countries such as the Philippines and Thailand, the fibres from these leaves are used to make fabric and vegan leather. This sector was almost non-existent in India, so we developed the technique of making yarn from pineapple fibres.”

Angika adds, “The process came with several challenges—for instance, India had no machines to extract fibre. Cleaning, drying, and converting the leaves into yarn was a laborious and time-consuming process. Sometimes the thread would break, and sometimes it would become too coarse.”

After months of effort, they succeeded in producing a yarn that was strong and durable, and had a natural silk–like sheen. The fibre also has properties that make it resistant to bacteria and sunlight. It’s three times stronger than cotton and absorbs sweat quickly.

Samiullah says, “The pineapple yarn has made us optimistic. It costs only INR 800 per kilo, while silk costs INR 7,000–8,000 per kilo. Pineapple yarn is lighter and stronger, and could bring international buyers back to Varanasi. Customers are intrigued when they learn that the saree is made from pineapple.”

Ashfaq Ahmad and Irfan Miyan, weavers from Lohta—the weaving hub of Varanasi—believe that while pineapple yarn can connect Banarasi weaving to global fashion, policies and reforms are needed at multiple levels to safeguard the interests of weavers. Amal Ansari, another weaver, adds that if the government makes the supply of pineapple fibre easier, it could breathe new life into their craft.

Aradhana Pandey is an independent journalist based in Varanasi. She writes on issues related to gender, environment, and social justice.

—

Know more: Learn how migrants in Madhya Pradesh are keeping the tradition of Maheshwari sarees alive.

Do more: Connect with the author at aradhana.panday10@gmail.com to learn more about and support her work.