At first glance, India looks like a global outlier when it comes to gender parity in science and allied fields: in 2024, women made up 43 percent of all awarded science-technology-engineering-mathematics (STEM) degrees. But upon closer observation, the pipeline is leaking at the very spot the country says it needs talent the most—engineering. In the flagship IIT system, only one in five first-year seats go to a woman. Across all engineering colleges in India, the share hovers at one-third.

This pattern can be observed even at the school level. Based on data from 650 Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas (JNVs)—a network of government-run residential schools for high-achieving students from economically marginalised communities and rural areas—across India, we found that 37 percent of girls choose the physics-chemistry-maths (PCM) stream after class 10. Less than half of these girls even register for the Joint Entrance Exam (JEE), which is an all-India standardised exam for admission to various technical courses, including engineering, at the undergraduate level.

Although JNVs nurture some of the country’s most academically promising students, including many first-generation learners, the gender gap in STEM choices remains stark. The question then is not simply why girls drop out, but why they do not enter STEM fields in the first place, and what factors affect their decision-making.

Why do so many girls steer clear of engineering?

Girls’ decisions around education are rarely driven by a single factor. At Avanti Fellows, we have observed that as girls enter senior secondary schooling in class 9, personal and societal beliefs, classroom experiences, and family considerations overlap and often reinforce each other, ultimately informing how they proceed with higher education.

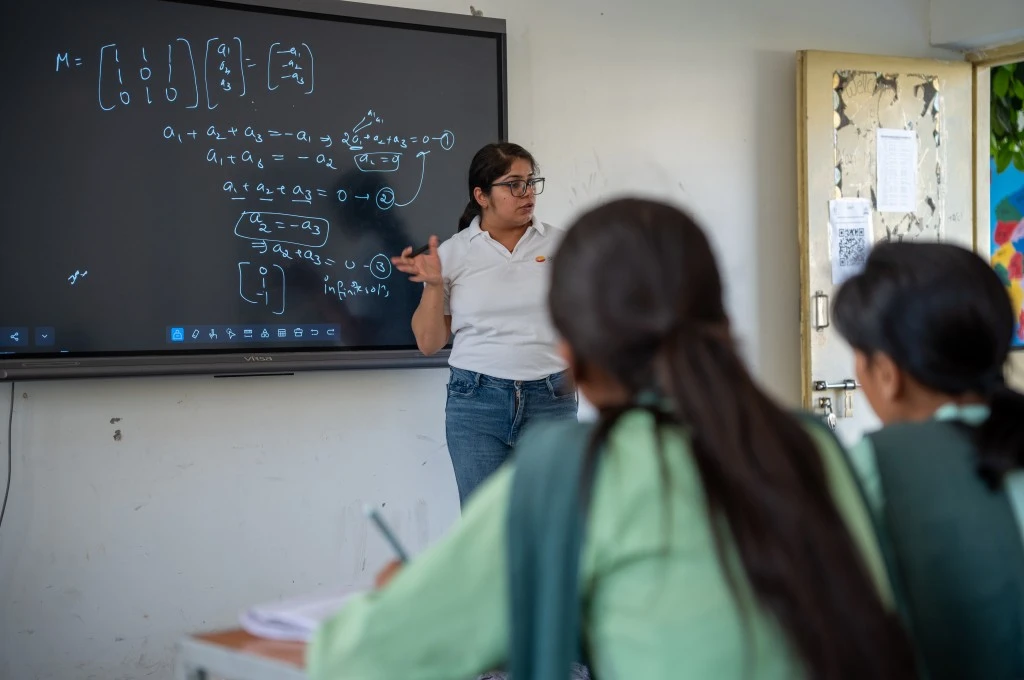

Avanti Fellows works with students in government schools to support them in gaining admission to STEM courses at the undergraduate level. Over the past three years, we have introduced targeted programmes for girls to understand and address the specific challenges they face in pursuing STEM. Based on our interactions with students from classes 9–12, these are some key reasons why this happens:

1. Maths and physics feel abstract and detached from real life

In many of our focus group discussions with girls in class 9 across JNVs, they shared that while they believed that they were as capable of being good at maths and physics as boys, they found biology more interesting. This interest was primarily driven by the perception that physics is ‘too abstract’. We observed that the sudden leap to highly conceptual content nudges girls towards biology, which they perceive as more grounded. Over the course of participating in STEM clubs, class 9 girls shared that their interest in a subject is one of the main criteria for selecting the course they would like to study in the future. As a result, their lack of interest in physics and maths prevents them from pursuing engineering in college.

2. Engineering is seen as less ‘purposeful’ than medicine

Almost all the girls who aspire to be doctors say that they would do so to help their communities. As a student from Arunachal Pradesh shares, “Healthcare is something that my village doesn’t have enough of. I’ve seen people lose their lives to illnesses that could have been treated or prevented if we had proper facilities. Becoming a doctor isn’t just a personal goal for me; it’s a way to help my people live healthier, longer lives.” These aspirations are often deeply rooted in personal experiences and driven by the need to address and overcome the challenges that girls may witness around them.

Conversely, a lack of interaction with role models—that is, women who are from similar backgrounds and are currently pursuing careers in STEM—has been a deterrent for girls to pursue engineering. They are unable to ‘see themselves’ in tech.

Research also shows that women gravitate to careers they believe will satisfy communal values of care, and engineering is often judged to fall short on this account. This is also rooted in how women are socialised from an early age to prioritise care-based roles that embody values of helping and healing. Through societal and familial expectations, media representation, and educational experiences, girls are consistently directed towards careers such as medicine, teaching, or social work, which are framed as inherently nurturing and oriented towards helping others. Our focus groups mirror this: girls describe medicine as ‘serving society’, while simultaneously not giving much thought to the role that engineering could play in positively impacting society through innovations in technology or infrastructure, for instance.

3. Parents hedge for safety and social respectability

In a rural Karnataka school, one of the students we spoke to said that her parents had told her, “Hospitals need doctors everywhere; factories are far away and often unsafe.” Parental calculations regarding their child’s safety, logistical concerns around travel, combined with factors such as familiarity with other women who may be pursuing similar career goals, often tend to nudge girls towards biology or even the civil services, away from the perceived risks of engineering colleges.

4. Classroom cues nudge girls towards biology

Long before the subject-choice forms arrive, many girls have already internalised a quiet message about where they belong in science. In everyday lessons, teachers often praise girls for the neatness of a cell diagram while complimenting boys on having a ‘logical maths brain’. They often encourage more boys to take up projects on robotics or to solve trickier physics problems. While these micro-signals are usually unconscious, when clubbed with a lack of female role-models in engineering and parental preferences for seemingly safer and more proximate careers, they make biology feel like a path where girls are more likely to succeed.

What we tried to do

In 2022, Avanti Fellows started working on targeted STEM engagement based on continuous learning and adaptation. We began with a 20-hour life skills programme focused on building girls’ agency and confidence for informed career decision-making. In year two, we expanded to 450 girls across eight schools, incorporating gender-focused conversations into a blended programme. However, while girls reported increased confidence, this did not translate into different subject choices for class 11.

In year three, this crucial insight led us to pivot towards hands-on STEM clubs that directly addressed why girls avoid maths in class 11. Through coding and electronics workshops, problem-solving sessions, data analytics modules, and meaningful interactions with engineers, we aimed to make STEM more tangible, accessible, and connected to real-world impact.

What worked, and what didn’t

1. Getting an experiential feel of the stream helps

Approximately 60 percent of the girls across five JNVs where we ran STEM clubs shared that the immersive experience of different careers such as data analytics, architecture and urban planning, electronics, and coding made them reconsider their career plans. Engaging in hands-on activities that used physics and maths, such as making cards with LED bulbs, helped students see themselves as builders and creators.

2. Early exposure sparks interest, but decision-making requires guidance

Our experience has shown that while many girls in class 9—especially after a year of STEM club engagement—expressed a strong interest in engineering and began to see it as a viable career path, this initial enthusiasm didn’t always translate into choosing maths in class 11.

This is why timely guidance and intervention are crucial, particularly during the transition to senior secondary school when students select their subject streams. Career counselling at this stage plays a pivotal role in helping girls make informed and confident choices.

Comprehensive discussions about the opportunities that mathematics can unlock, along with clear, factual information about available courses, colleges, and placement prospects, can make a significant difference. Most importantly, online or offline interactions with women who are engineering students or working in the field can serve as a source of inspiration and guidance.

3. Increased interest and confidence are not enough to bridge score gaps

While STEM clubs can spark interest, they are not enough to prevent academic slippage, especially in competitive exams. For instance, we observed a five-point difference in the JEE results of class 12 girls and boys from the JNV schools that we work in. This indicated that despite studying in the same residential schools and receiving the same test prep and career guidance interventions, girls were scoring lower than boys in the JEE.

Even when girls enter class 11 with similar baseline scores, they tend to fall behind by the time the final JEE exam is held. This underscores the need for classroom teaching that actively works towards equal outcomes. Teachers must make the application of concepts explicit, encourage girls to speak up and ask questions, and use test data to identify and address learning gaps. Regular small-group counselling sessions based on this data can offer targeted feedback and support, helping girls stay on track and build confidence.

When asked what would help them succeed, girls in our programmes consistently highlight specific needs: they want teachers to pause and check if students are able to keep up what is being taught rather than rushing through content, and give more working examples that connect abstract formulas to real-world applications. Many express that mixed-gender study spaces sometimes make them hesitant, as they worry about being teased or judged for giving wrong answers, preferring to ask questions after class or in a small group when they’re unsure.

Girls also value teachers who normalise mistakes as learning opportunities and affirm and encourage curiosity. One student noted, “When the teacher says ‘good question’ even when I think it is a basic one, I feel like asking more.”

In the year 2025–26, our team has developed a framework and guidebooks for teachers to build their mindsets and capacities to address the specific needs of girls in their classrooms, including by sharing gender-disaggregated test outcomes data with teachers and helping them conduct small-group counselling with students.

4. Parents play a vital role

Most of our work in the Girls in STEM programme has so far focused directly on students. Through this, we realised that parents play a crucial role in shaping their daughters’ aspirations, self-belief, and ultimately their choices of courses and careers. We also observed that parental influence tends to be stronger on girls in our programmes than on boys. Building on this insight, we are now planning to work closely with parents—both through in-person workshops and online sessions—to raise exposure and awareness about professional options. These sessions will also address misconceptions about further education and careers STEM, and highlight the vital role parents play in supporting their daughters’ academic journeys, including choices that may involve studying away from home.

The journey is ongoing, and so is the learning

We don’t have all the answers yet. Our work over the past three years has been a process of experimentation and discovery.

No single factor can explain why girls don’t opt for engineering. These decisions are shaped by a web of influences—academic performance, classroom dynamics, parental expectations, peer behaviour, exposure, and self-doubt—that often reinforce each other. Addressing just one barrier in isolation is unlikely to create lasting change. As such, what is needed is a comprehensive approach that tackles multiple challenges at once, and an effort to try different interventions to understand which ones can move the needle most effectively.

We began with a life skills approach, shifted our focus to gender and aspiration-building, and then moved towards fostering confidence and curiosity through hands-on STEM clubs. Along the way, we have realised that being able to sustain interests throughout the high-pressure years of classes 11 and 12 is critical.

At present, we are focusing on senior secondary interventions and exploring whether a strong, focused career guidance programme at the start of class 11 can help more girls—especially those who have already chosen science—to not drop maths. We are also engaging parents more intentionally to help make engineering feel like an aspirational and attainable choice. Moreover, it is equally necessary to build the capacity of teachers to be able to facilitate equal outcomes for both girls and boys. For this, we are working with teachers to support students as they prepare for competitive exams through small-group mentorship sessions. These conversations are designed to help students build clarity on long-term goals, manage the stress of balancing board exams with JEE/NEET preparation, and reflect on their progress. The small-group sessions also focus on improving time management, leveraging support systems such as parents and peers, overcoming academic backlogs, and sustaining motivation.

Recognising that mindsets play an important role in both academic performance and long term success, we are piloting wise interventions in classes 11 and 12 to understand whether addressing psychological barriers might enhance academic performance and open pathways to more ambitious subject and career selections.

By creating space for reflection and confidence-building, we aim to ensure that students, especially girls, can navigate challenges and pursue higher education. The journey is far from over. But with each initiative, we are getting a little closer to understanding what it will take to truly level the playing field in STEM.

This article was updated on September 1, 2025 to incorporate information about the introduction of wise interventions for students in classes 11 and 12.

—

Know more

- Learn more about the gaps and challenges that impact girls’ access to STEM education.

- Understand the importance of early and inclusive career guidance for schoolchildren.

- Read about the factors influencing women’s participation in STEM fields in India.