READ THIS ARTICLE IN

Left for debt: Microfinance fractures families in Kushinagar’s villages

Over the past decade, a growing number of microfinance companies has been entering villages in Uttar Pradesh’s Kushinagar district. These companies’ loan agents primarily target women from marginalised communities, who are otherwise denied access to bank loans due to lack of property titles or other sureties.

I belong to the Musahar community, and through my work in Kushinagar’s villages I have seen first-hand how microfinance loans have worsened poverty and exploitation.

The companies form groups of women and give each member a starting loan of INR 20,000–25,000. Interest rates are as high as 22 percent, and instalments have to be paid on a weekly, fortnightly, or monthly basis. In addition, people are borrowing money from different microfinance companies at the same time. A woman recently told me that she had taken out 15 separate loans, amounting to approximately INR 3 lakh.

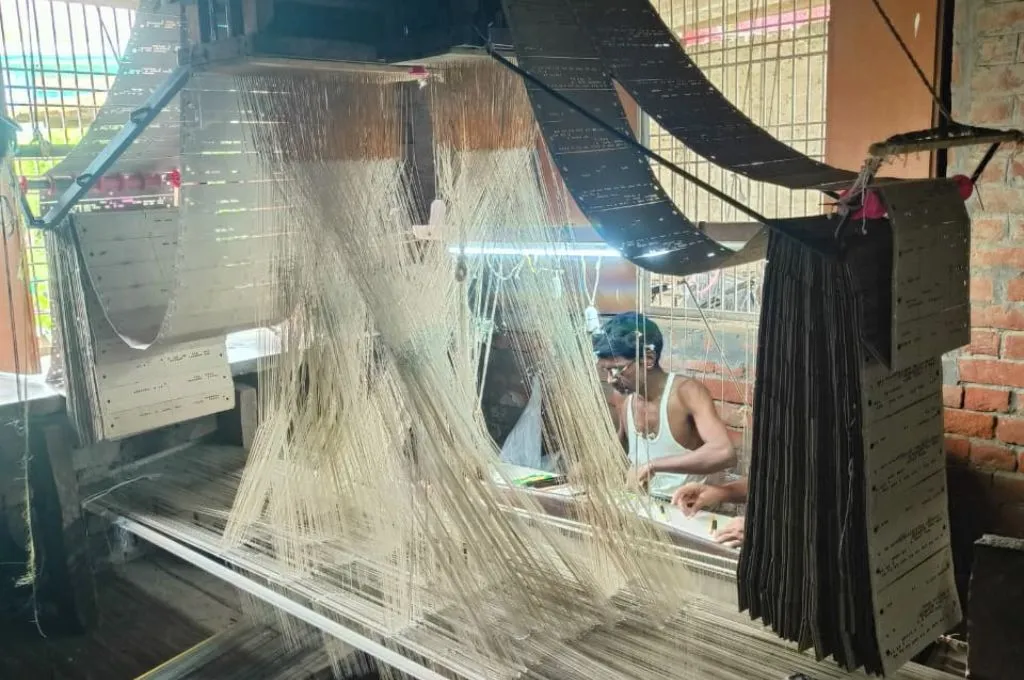

Families take out these loans because they need the money for various reasons, such as their child’s education, a marriage in the household, or starting a business. Most of the men in my community migrate and find work as daily wage labourers, but it is not always possible for them to take their families along. As a result, women—who often stay back and take care of the household—are targeted by microfinance companies.

While advancing a loan, agents ask for ID proofs of the woman and her closest male relative. However, since men often leave the village, it is the women who face the brunt of abuse and harassment from loan agents.

Women in the community primarily engage in farm work or home-based animal husbandry. Their daily wage for farm work—already seasonal and increasingly scarce due to factors such as mechanisation—is INR 120–150. This is not enough for a family to survive on, let alone to pay off debts. In many cases, loan agents have broken down people’s front doors, barged into their homes, and harassed women until they pay up. There have even been reports of deaths of people trapped in debt by microfinance companies in the district, including the case of a young Musahar man in Jungle Khirkia village in 2024.

To make matters worse, in some cases, although women from the community take out loans in their name, the money is pocketed by someone else in the village—often members of the dominant caste. They hand women cash in exchange for the loan amount disbursed by the company and assure them that they will pay the instalments. However, they stop making payments shortly after, so microfinance agents track down the person listed on the loan documents.

Unable to pay the money back, many young families are fleeing their villages to escape the threats and harassment. Newly-weds and young couples with children are leaving behind elderly parents, whose conditions have worsened with no one to care for them. Being forced to flee has also affected children, with many forced into child labour as families are unable to provide an education.

Last year, heavy rains and waterlogging left many people without any work. People began demanding that the government waive microfinance loans. At the time, the district magistrate stated that while the government could not waive debts issued by private companies, it could provide temporary relief. The authorities sent out an official notice ordering company agents not to harass families who were unable to make payments.

Since then, there have been fewer reports of loan agents persecuting women. But the debts have not disappeared. The sub-divisional magistrate of Kushinagar’s Kasia block also met with bank managers, urging them to give people access to government loans. However, they refused, saying that loans could not be given to people who could not furnish property or land deeds as collateral.

As livelihood sources decline and bank credit remains inaccessible, marginalised communities are left with few options but to turn to the predatory loans offered by microfinance entities.

Durga is a human rights defender (HRD) associated with ActionAid India.

—

Know more: Read more about the impact of group-based loans on vulnerable rural communities.