In flood-hit rural Mizoram, it costs INR 20 to charge a phone

I live in Damparengpui village in Mizoram’s Mamit district. Like many other parts of the Northeast, this area has experienced incessant rainfall since the beginning of June, resulting in power outages throughout the district. Landslides across the state have made it challenging for people in Damparengpui to travel to other parts, which has led to a breakdown in communication. We, like everyone else, have become overly dependent on smartphones to stay connected, but we don’t have any electricity to charge our phones.

Within a week of losing power supply in the village, our phones ran out of battery. It was then that two residents of our village, Sanga and Liana, came up with a creative solution to the problem.

Both of them are shopkeepers and use generators to power their refrigerators so they can keep ice creams and meat fresh and frozen. These same generators are now being used by the entire village to charge their phones daily.

The generators run on petrol, which is bought and stored in bulk. Sanga and Liana take a payment of INR 20 to charge a phone and INR 40 to charge a power bank. With 2–3 litres of petrol, a generator can run for over an hour and charge approximately 50 devices using extension cords that are attached to it.

When the generator recharges, we wait till we receive a message from the shopkeepers. They do this either on phone or by sending someone to tell us that we can visit again. Usually, their shops remain open from 10 am–12 pm and then again from 6–9 pm.

In our village, we struggle with power cuts even when there are no floods. However, this year is the longest we have gone without power. Having our phones charged becomes extremely crucial not just to contact hospitals and authorities in case of emergencies, but also for day-to-day business. While some of us use the phones to contact our children and family members living away from the village, others use them for watching the news on YouTube, accessing Facebook, and making online payments to buy groceries as going to the ATM has become difficult.

We can keep waiting for the power to come back, but there is no certainty on when that will happen. The generator helps us cope with the situation in the meantime.

Rodingliana is an IDR Northeast Media Fellow, 2024–25.

—

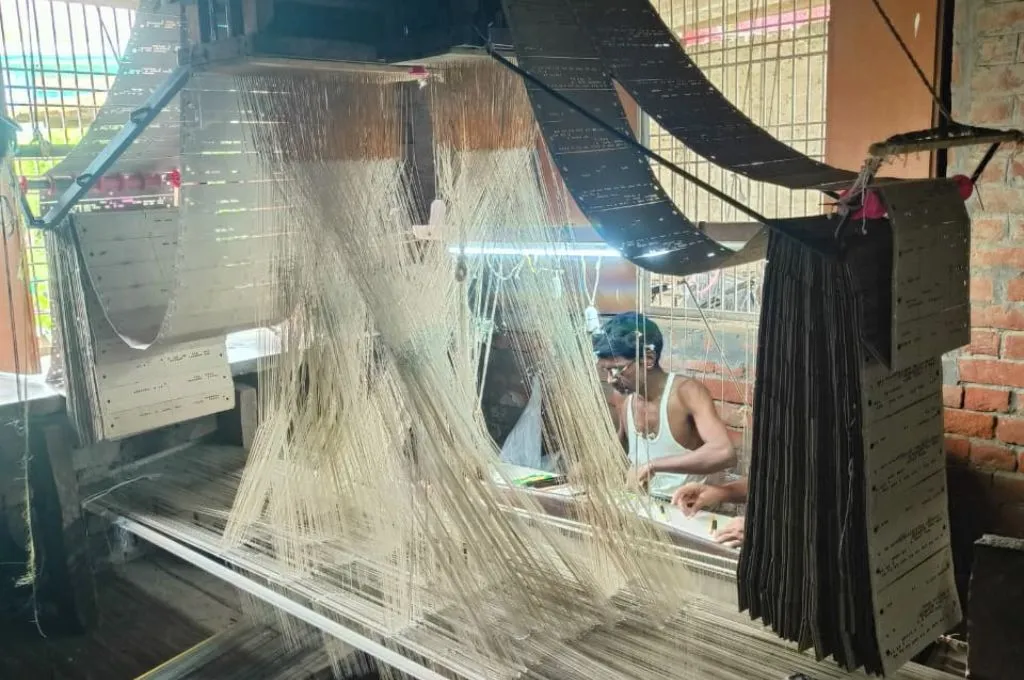

Know more: Learn how women in rural Nagaland are bartering silkworms for castor leaves.

Do more: Connect with the author at rdaapeto157@gmail.com to learn more about and support his work.