India is a young country, and it’s getting younger. The UNFPA’s State of World Population Report 2023 reveals that approximately 70 percent of the country’s population is under the age of 35, and close to 40 percent is below 18. By 2030, it will have the world’s largest working-age population—more than 1 billion people between the ages of 15 and 64. It is, therefore, time to rethink how young people, many of whom will be living in rural India, engage with and shape the nation’s future.

More than three decades ago, the 73rd Constitutional Amendment institutionalised local self-governance, empowering gram panchayats to make decisions for their communities. It was a radical shift, placing power in the hands of the people. But today, as India sits on the edge of a youth-driven transformation, we must ask: How well are we integrating this rising generation into the governance processes that affect their everyday lives?

Student participation models in local governance

Across India, state- and civil society–led models are offering practical pathways for student participation in local governance.

- In Odisha, the children’s cabinet model is enabling students to simulate governance roles within schools. Each student-led cabinet has a prime minister, a health minister, an education minister, and so on, who work on school governance and community interface.

- In Maharashtra’s Nandurbar and Amravati districts, tribal and rural schools conduct bal sabhas. These are monthly student assemblies where children discuss school issues, track midday meals, absenteeism, and sanitation. These are often linked with local gram sabhas. Additionally, the state supports bal patrakars (child reporters), who document community issues and submit them to local leaders and media outlets. In 2021, child reporters helped in reducing alcohol abuse and open defecation in their villages by creating issue-based campaigns.

- Jharkhand’s school child cabinet model mirrors Panchayati Raj Institutions and has been implemented in more than 30,000 government schools as per the state’s education department. These child cabinets organise school functions, promote peer learning, and connect with school management committees (SMCs). In Simdega district, child cabinet members have been part of community consultations for improving school infrastructure and ensuring attendance among girls.

Another such model is the makkala grama sabha, or children’s village assembly, which has been pioneered in Karnataka.

Makkala grama sabhas are designed to give children the opportunity to identify and present issues that matter to them, such as sanitation in schools, safe transportation, or the safety of animals. They typically bring together 150–250 children from five to six nearby villages. Alongside them sit an eclectic mix of adults—panchayat presidents and vice presidents, panchayat development officers (PDOs), cluster resource persons (CRPs) from the education department, ASHA and Anganwadi workers, schoolteachers, local health and child development officials, and even representatives from the local police station. The first makkala grama sabha was held in 2002 in Keradi village, Karnataka, and since then many organisations have attempted to replicate this model.

These efforts have led to real-world results—new playgrounds, functional toilets, improved roads. More importantly, they’ve catalysed a shift in mindset.

Experimenting with makkala grama sabhas

In a recent pilot, Involve organised makkala grama sabhas in two schools under the Bannerghatta and Shantipura panchayats in Anekal block, Karnataka. In addition to voicing their concerns to the gram panchayat, the selected students were trained to identify issues, develop actionable solutions, implement these solutions, and present their outcomes at the makkala sabha.

Our aim was twofold:

- Observe whether this process could boost students’ self-efficacy.

- Understand whether it could shift adult mindsets about student voice and participation.

We began by listening to and engaging with students, panchayat members, teachers, and community stakeholders to understand the deeper currents shaping how participation is perceived and practised at the local level.

One of the insights we gained was that for children to be taken seriously, they must first be heard seriously. In addition, rather than imposing ourselves on existing panchayat structures, we chose to work alongside them. We also invited local leaders, ward members, panchayat functionaries, and heads or representatives from departments such as education, health, and women and child development to note how children are participating in the sabhas. This was done to shift the narrative about both children’s participation as well as what inclusive governance can look like.

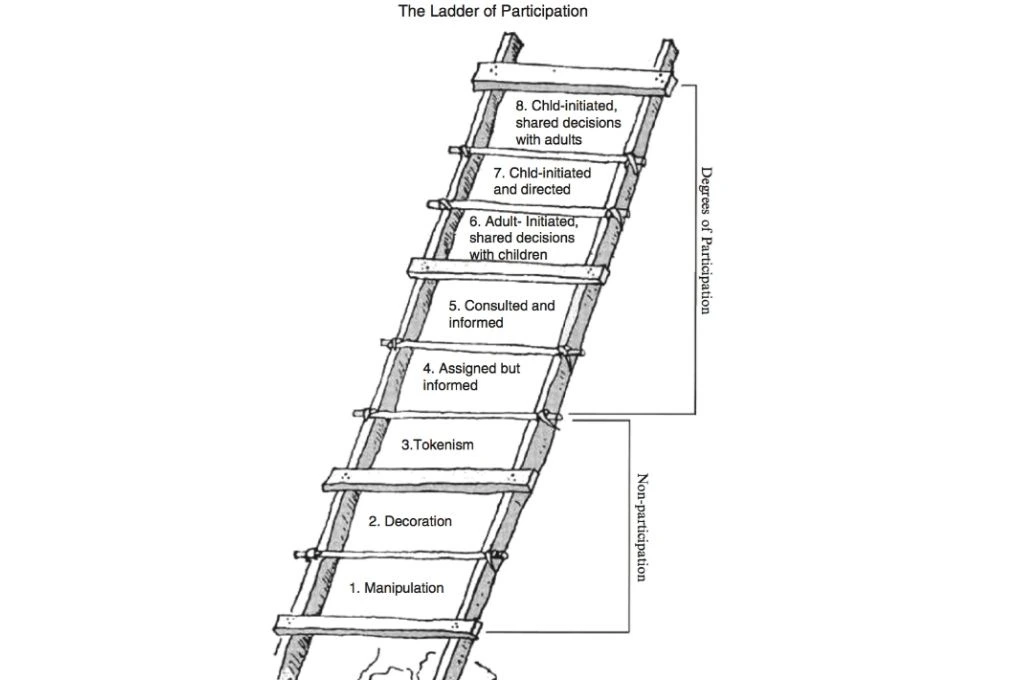

Our baseline interviews uncovered a telling pattern: Most adults believed that students could only speak to issues within the school. To better understand these initial perceptions, we turned to Roger Hart’s Ladder of Children’s Participation and treated it as our guiding framework. The model outlines eight distinct levels of children’s participation in decision-making, ranging from tokenism to genuine partnership. It is widely used to assess how meaningfully children are involved in shaping decisions that affect their lives, be it in schools, communities, or governance structures. The model enabled us to critically reflect on the quality and depth of participation we observed, asking not just if children were involved but also how and to what extent they were truly being heard.

It became clear to us that the panchayats perceived student involvement as mostly decorative. This is what Roger calls Rung 2, where children are present but not truly engaged or informed. Gram panchayat members would visit schools occasionally and ask about school-specific concerns, but never saw students as contributors to broader community discussions. As one panchayat member said, “Students usually know about problems related to students, but they won’t know much about outside problems.”

What has changed?

1. The shift in children’s attitudes

Tejaswini,* a student at GHPS Bannerghatta shares that at first she would think, “Will they even listen to us? We’re just children. What if they don’t take us seriously? What if they think that it is not our place to speak up?”

Many of the children were hesitant like her. However, through consistent preparation and encouragement, the students began to feel more confident.

They started speaking about issues such as the lack of access to safe drinking water, inadequate drainage system and waste management, and gutka spitting near school premises. The adults too began to pay attention after some time. When some of the panchayat members and other authority figures started to listen, and even act in some situations, it further boosted the children’s confidence.

2. The shift in panchayats

While none of the panchayats formally adopted the solutions proposed by students, they began to view the students as bridge builders, capable of raising awareness among parents and neighbours. From decorative involvement, we had moved to Rung 4—assigned but informed. Here students had a clear role, understood the process, and contributed meaningfully.

Gram panchayats were also responding. They started visiting sites flagged for garbage accumulation or water issues, prompted directly by what students had shared. These actions suggested that student participation was no longer being dismissed; it was capturing adult attention and resulting in action. There was a growing openness to move towards more structured and regular forms of student engagement, and an emerging recognition that systems would need to evolve to support this more effectively.

What are the gaps that remain?

1. Building a sense of ownership among children

A significant challenge we encountered was supporting students in feeling a genuine sense of ownership in the makkala grama sabha. Many children are still reluctant to speak up—understandably so, given the formality and scale of the setting. There is often a feeling of awe, even intimidation, that can prevent full expression. It becomes essential, therefore, that panchayats and all stakeholders continue to create student-friendly spaces where children feel safe, heard, and confident, and where speaking up feels natural, not daunting.

To this end, it would be valuable to ensure that the primary focus of the sabhas remains on children, as they are the core purpose of these gatherings. While it’s understandable that adult felicitations and acknowledgments are part of the event, finding the right balance can help keep the spotlight on children’s voices and participation.

2. Perceiving children as messengers, not problem solvers

Although adult mindsets have shifted, and action has also been taken in some instances, students are still largely seen as messengers and not independent problem solvers. This falls short of the desired goal—the acknowledgement of children’s capacity to identify, frame, and resolve issues that matter to the entire community.

In fact, the limited two-way dialogue during the gram sabhas was a major gap. While students presented their ideas, panchayat members rarely engaged in conversation or provided feedback. This lack of dialogue pointed to a broader disconnect in collaborative intent, particularly in discussions tied to resource allocation and shared decision-making.

The perception of children as mere messengers resulted in an overreliance on adult perspectives; officials tended to prioritise observations from adults, often sidelining the voices of children. Shifting this mindset proved challenging, especially in the absence of any structure to children’s engagement prior to the makkala grama sabha pilot. While students are increasingly being seen as serious actors, their inclusion still often stops at raising concerns. The next frontier lies in making this shift truly meaningful by involving children more deeply in thinking through issues, co-creating ideas, and planning alongside gram sabha members. This would mark a real move towards shared ownership, where children are not just voicing concerns but actively shaping outcomes. Until then, even when children are taken seriously, it will not be seriously enough to trust them with the process itself.

3. Overcoming administrative roadblocks

Additionally, administrative roadblocks continue to hinder follow-through. Many issues raised by children, though acknowledged, struggle to gain traction amid other competing priorities of the gram sabhas. Better systems need to be introduced to look at these issues more sustainably. Other countries offer useful models. In Norway, every municipality is required by law to have a youth council representing children and young people, with an advisory role in municipal decision-making and mandatory consultation on issues affecting them—leading to changes in public transport, sports facilities, and even school curricula. In New Zealand, child and youth councils run by local authorities are elected bodies that meet regularly with council officials, participate in policy committees, and contribute to budget consultations, influencing initiatives such as safe cycling infrastructure and youth mental health programmes. Adopting such approaches can ensure that children have a formal and recognised place within the decision-making apparatus of local governance in India.

If India is to harness the potential of its young population, it must move beyond symbolic participation to create formal, sustained avenues enabling children to influence decisions that shape their communities. The experiences from makkala grama sabhas show that there is promise, and when children are given space, preparation, and respect, they can surface fresh insights, galvanise action, and bridge generational gaps in governance. Embedding such participation deeper within the very structures of local decision-making—much like youth councils elsewhere to which children are officially elected—will not only strengthen democracy at the grassroots but also prepare a generation of citizens who see themselves as co-creators of the nation’s future.

*Name changed to maintain confidentiality.

—

Know more

- Read this report on child-responsive local governance.

- Learn more about what makkala grama sabhas need to function effectively.