READ THIS ARTICLE IN

Stitching a future: Women from the Kalandar community weave together livelihoods

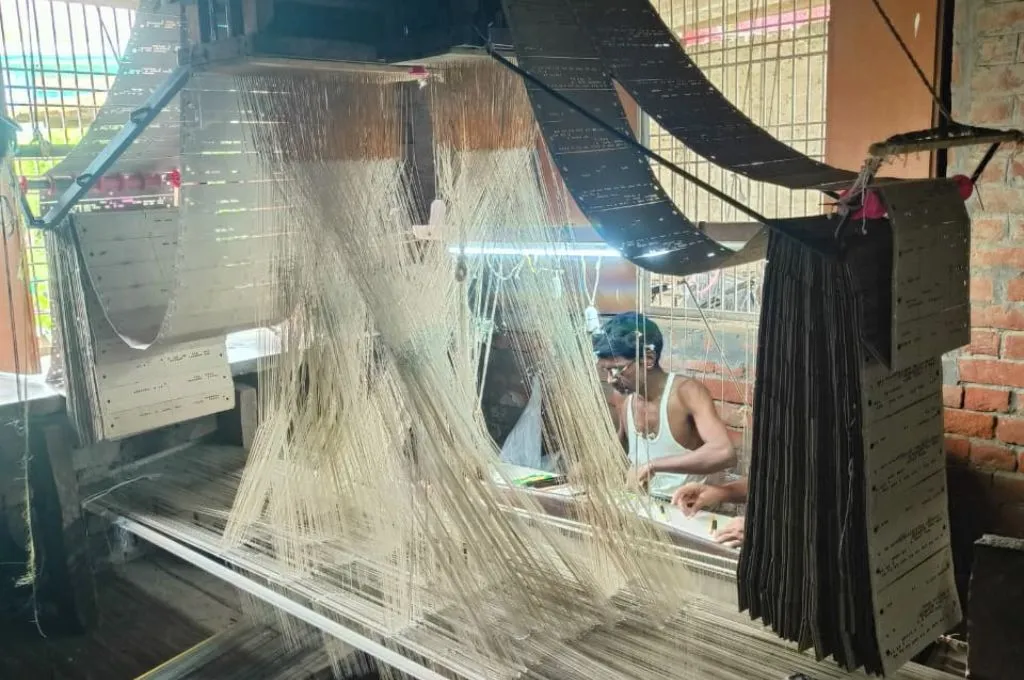

Aari-tari is a special kind of embroidery work. Our people—the Kalandar community—learned this craft to make a living. The Kalandar community falls under the Denotified and Nomadic Tribes (DTNT) category. In the past, the men earned a livelihood by entertaining people by with bear performances. However, after the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 was enforced, this work was banned. Following this, the women and girls from the Kalandar settlement in Tonk got into aari-tari work to support their families.

In 2014, with the help of Wildlife SOS, my father-in-law—a social worker—established an aari-tari centre in Tonk. Acquiring this new skill gave us a new means of livelihood. After our community’s traditional way of earning had been taken away, the financial situation of Kalandar households deteriorated drastically. Most of us studied only up to grade 5 or 8 and then started working. In several families, someone had to leave school so that younger siblings could continue their studies. I supported my younger siblings’ education, as did many others.

Now we are not only earning money but also gaining respect from our families and community because we are contributing to the household income. The work allows us to earn INR 300–400 per piece and we love doing it, especially when together. Usually, 10–12 people work together at the centre. A supplier brings the raw materials, which are processed in a factory. We select the designs, create the products, and then hand them back to the suppliers, who pay us.

This work has now spread throughout our community and has made life a little easier for our families. If similar centres are established in other large nomadic communities, more youths will get jobs and there will be a significant change in how Kalandar and other DTNT communities live. Young people will not sit idle, wasting their time roaming around or getting into fights. They will work, earn money, and contribute to their families’ incomes in a respectable manner.

Earlier, we lived in tents or slums and there were neither houses nor education; much has changed since then. After our bears were taken away, we had no work left, and even today, many people struggle without jobs. But efforts like the aari-tari centre have improved our situation, and we hope this change will continue to happen even faster.

Noor Jahan Kalandar does aari-tari work to support her family. She also trains others from the community in this skill. Noor Mohammad advocates for the rights of the Kalandar community and is part of a collective called Ghumantu Sajha Manch.

—

Know more: Learn how a group of youth from the Van Gujjar community are teaching birdwatching and other unique skills to earn livelihoods.

Do more: Connect with the authors at noormohammadtonk@gmail.com to learn more about their work.