Punjab is the leading state for its cultivation of kinnow, a high-yielding mandarin (a hybrid plant), with an average cultivation area of 59,000 hectares. The town of Abohar in the Fazilka district alone contributes 60% to the overall state production. The harvesting season for this fruit commences in December, and continues till March, with the peak yield observed during January and February.

This year’s kinnow harvest has been exceptional, due to favourable temperatures during the crop’s flowering stage, resulting in an anticipated output of 13.5 lakh metric tonnes. However, this bumper harvest has led to a significant decline in farm gate prices. The farm gate value of a cultivated product in agriculture is the market value of a product minus the selling costs.

The fruit used to fetch Rs 20-30 per kilogram. However, this year, farmers are getting only Rs 6-12 per kg.

Successive state governments had been dilly-dallying on the implementation of several crop diversification measures, and consequently, wheat-paddy monoculture is going on in the state unabated. While kinnow cultivation has been promoted as a competitive cropping alternative for farmers in southwest Punjab, the precarious pricing dynamics and weak institutional arrangements associated with it may not counter the dominance of a wheat-paddy monoculture.

Economic viability of kinnow cultivation

A farmer will diversify from paddy to other crops if the returns are not only promising but also significantly higher than those from paddy.

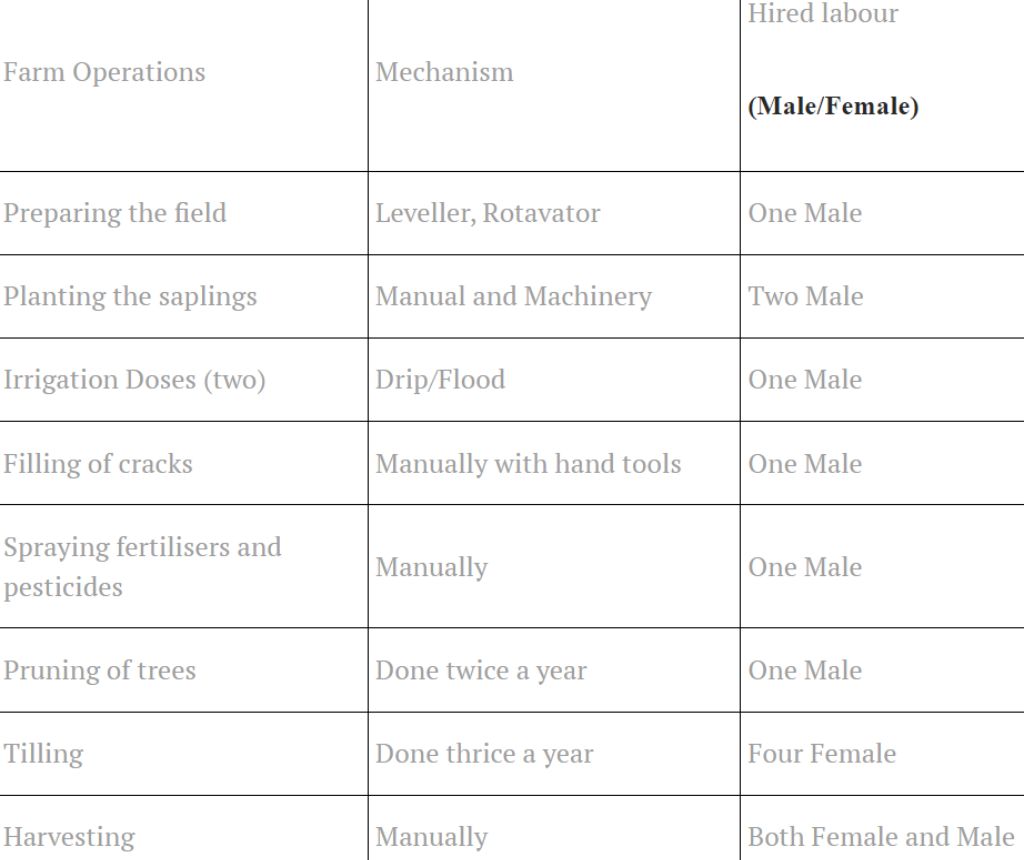

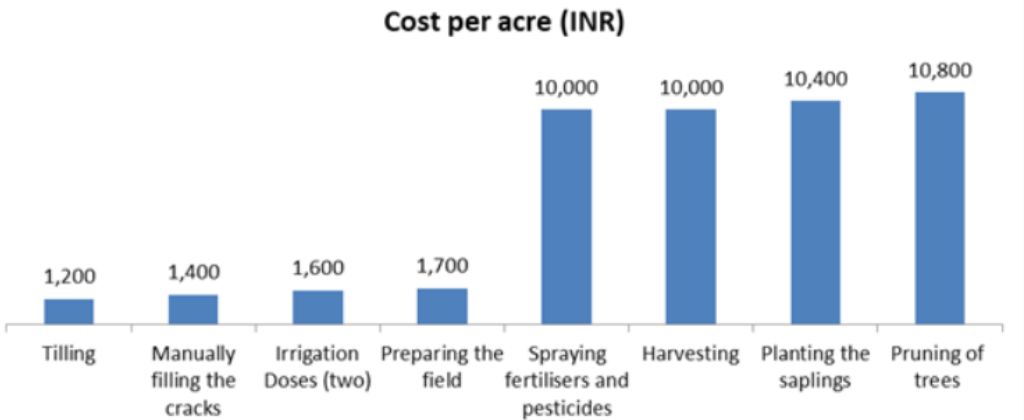

We assessed the cultivation practices of kinnow and calculated the operational cost per acre based on the interactions with farmers from Jandwala village in Abohar.

Kinnow cultivation is quite laborious throughout the crop cycle and depends heavily on both hired and family labour. As compared to wheat and paddy, this crop is quite fragile as it requires the family labour to continuously micro-manage crop safety during and before the harvesting months.

Strenuous farm operations generally favour male labour, while for tasks such as tilling the soil and harvesting, female labour is preferred, as they do the work very neatly and are also available at lesser wage rates.

Farm operations based on labour

The incubation period, from three to four years, and the wear and tear of the plants are inseparable parts of the cultivation cost. The overall cost of cultivating kinnow per acre is Rs 47,000. The average yield from a kinnow farm is 100 quintals per acre, with an average farm gate price of Rs 700 per quintal this year. Consequently, returns per acre amount to Rs 70,000, and net returns over operational costs are Rs 23,000 per acre.

Comparatively, last year’s average price of Rs 2,500 per quintal resulted in net returns of Rs 2.03 lakh per acre. This demonstrates significant price variations and fluctuations in profit margins. On the other hand, paddy, with an average cost of Rs 20,000 per acre, yields net returns of around Rs 45,000 per acre. Paddy is a stable crop for farmers, with fewer fluctuations in returns due to open-ended procurement by the government with a minimum support price (MSP) and its weather resilience.

Furthermore, paddy is a relatively less labour-intensive crop. It does not require any micro-management as the harvesting is fully mechanised. This makes paddy an obvious choice for the farmers.

Market fluctuations

After bearing high investments in kinnow production, farmers have to face market asymmetries each year. Over the past few years, effective post-harvest management for kinnow growers has been lacking. There is an absence of processing units to absorb local kinnow production. While several private waxing and grading plants have emerged in the area, thanks to traders and business entrepreneurs, there is currently no buyback guarantee or price surety for the produce.

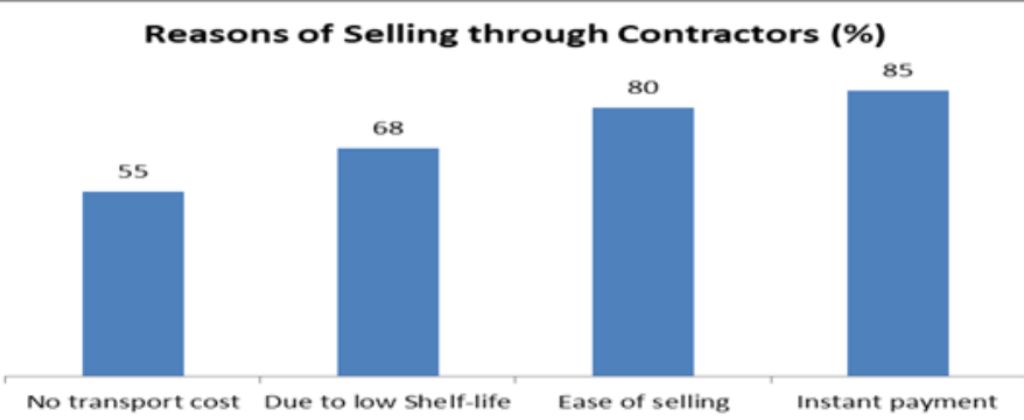

Despite the existence of a well-established citrus mandi in Abohar, it does not guarantee farmers a favourable price, even when factoring in the costs of transportation, loading, and unloading. Consequently, farmers find themselves heavily reliant on agents or contractors for marketing their produce. Given the perishable nature of the product, contractors play a crucial role in kinnow procurement, and as a result, price determination is largely dependent on them.

The contractors supply the fruit to other states, such as Delhi, Karnataka, and Jammu and Kashmir. The fruit is also supplied to other countries, such as Bangladesh and Nepal. Contracts are finalised in June and the rates are fixed on the basis of the number of flowers on a tree that indicate the output of the fruit. These contracts are not directly established with the companies, but are intermediated through a number of agents who further market the fruit. Payments are directly transferred to the bank accounts of the farmers. In case of any delay, an extra amount is also paid. Agents bear the entire cost of picking the fruit from the farms, which includes loading and unloading, grading and waxing.

Selling through contractors is found to be the most convenient marketing method, despite the fact that the prices offered by contractors are among the lowest across all marketing channels. As contractors form their cartel and prices are largely influenced by the market forces, it creates asymmetry of bargaining power in favour of buyers.

However, farmers prefer contractors because of the prompt payment they provide. Many smallholders have expressed the need for immediate cash after the harvest to settle loans from commission agents and moneylenders.

Hence, due to the lack of proper governance over an assured marketing system and value chain, kinnow has remained a risky investment for small growers, even when there is a niche demand within and outside Indian markets.

The way forward

The cost structure of kinnow cultivation suggests that it requires relatively more investment on labour, machinery, micro-management, and skill-level. As compared to paddy, the opportunity cost of establishing a kinnow farm is relatively higher. Therefore, it seems to be a risky affair to venture in, especially for small holders.

Hence, paddy is an obvious choice for the farmers in Punjab, as there are no economically stable and rewarding alternatives.

In fact, Punjab has been the top contributor of paddy in the central pool of food grains for the last ten years. Hence, blaming Punjab’s farmers for cultivating paddy and its consequential impact on the environment, especially during the seasonal rise in air pollution in Delhi, is a classic case of the pot calling the kettle black.

Thus, several measures need to be taken to safeguard kinnow growers. The agro food industry should be given priority to absorb the produce locally. Building relationships with food processors, juice manufacturers, and other agribusinesses can create a stable market for kinnow growers. Additionally, small and marginal farmers need hand-holding support from the government to diversify.

This article was originally published on The Wire.