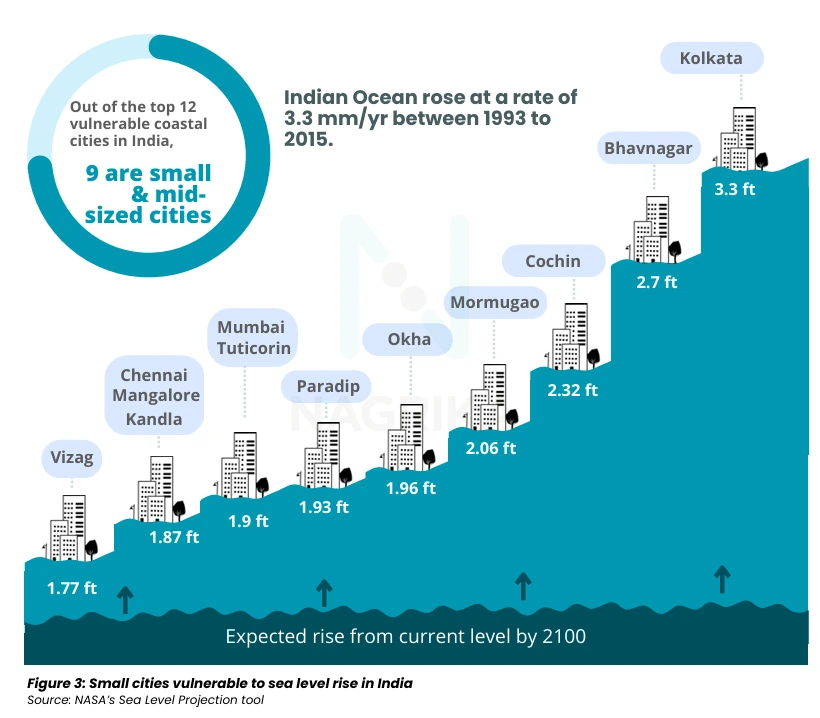

Sea-level rise poses significant threats to coastal cities worldwide, including erosion, flooding, groundwater contamination, and loss of vegetation and aquatic life. In India, there are 113 cities spread across nine states that are at risk of getting submerged due to sea-level rise by 2050. Out of these, 109 are small and mid-sized coastal cities.1

Some of the most vulnerable cities are located in Gujarat and Kerala, where coastal erosion is occurring at a high rate. Smaller and mid-sized cities such as Kochi and Visakhapatnam face imminent risks of inundation and infrastructure damage.

However, much of the literature and discourse on climate change–induced sea-level rise disproportionately focuses on large metropolitans such as Mumbai and Chennai. There is little to no research on the risks faced by small and mid-sized cities, leading to a lack of attention and tailored solutions for these vulnerable areas.

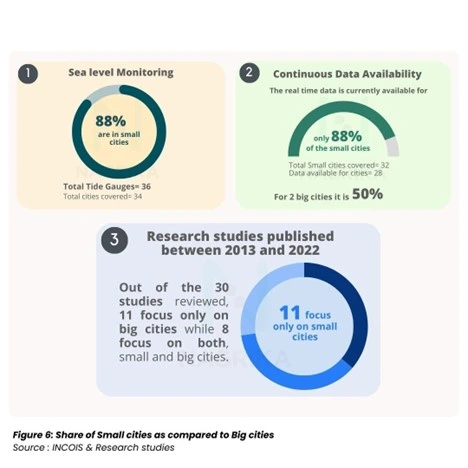

To understand this better, we at Nagrika conducted a study on the effect of rising sea levels on small and mid-sized coastal cities. Our research involved a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, climate data, and monitoring networks, with a focus on smaller urban centres. We examined the share of small and mid-sized cities in data monitoring, data availability, and research studies related to sea-level rise.

Here are some of the needs of such cities as they confront the force of climate change.

1. Address gaps in data monitoring

Currently, there are gaps in data monitoring for various kinds of climatological data in smaller Indian cities. These issues include limited data availability, continuity, and consistency across monitoring stations, as well as inadequate infrastructure and disparities in equipment. For example, our analysis found that continuous PM2.5 data for 2018, 2019, and 2020 is available for only 74 out of 241 small and mid-sized cities in the NAMP dataset.

Collecting and maintaining data on sea-level rise presents even greater challenges. Sea levels are monitored through a combination of tide gauges and satellite altimetry (a technique that measures the height of the ocean). Tide gauges provide long-term data from coastal locations, but their coverage is limited to the areas where they are installed. Satellites, on the other hand, offer comprehensive global data by measuring sea surface height.

While tide gauges and satellite altimeters provide valuable data, there are challenges in terms of functionality and coverage, with real-time sea-level data currently available for only 30 small and mid-sized cities. Understanding sea-level rise also requires continuous data spanning several decades, making the process even more complex. Moreover, tide gauges, which are crucial for monitoring sea level relative to land, often face functionality issues. During our research, we found that only 30 out of 36 tide gauges are operational. This could be due to several factors, including maintenance challenges, technical issues, and human resource constraints. The non-functioning tide gauges likely lack the necessary sensors, such as radars or pressure sensors, to measure and report data. Satellite altimeters, while useful, are hindered by bad weather and track loss. Additionally, they can only monitor specific locations once every 10 days.

There have been some efforts towards improving data monitoring systems. An example is the Space Applications Centre (SAC), an institution of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), that develops space technology applications for communication, navigation, and remote sensing. In collaboration with the Central Water Commission, an organisation responsible for water resource management and development across India, SAC has created a Shoreline Change Atlas. The atlas is a comprehensive digital resource that depicts and quantifies shoreline changes as eroding, accreting, or stable, and shows the status of shoreline protection measures taken by respective states. However, this data lacks city-level specifics, limiting its utility for local planning.

2. Build robust research in small cities on the impact of climate change

The highest sea-level rise among the 109 small and mid-sized coastal cities is predicted to be in Bhavnagar, Gujarat, which is set to witness a sea-level rise of up to 2.7 feet (0.82 metres) by 2100. However, none of the 30 research studies on sea-level rise published between 2013 and 2022 that we analysed focused on Bhavnagar, pointing to the deficiencies in terms of knowledge creation, monitoring networks, and current data availability for smaller cities. While there is research on broader climate change issues such as groundwater being contaminated by seawater, flood risks, and weather forecasting in the larger Bhavnagar district, there is a notable lack of studies specifically concentrating on how rising sea levels will impact Bhavnagar city. This is true for most small and mid-sized cities; existing studies don’t give a detailed analysis of how rising sea levels will affect the city’s infrastructure, economy, and residents. Such a gap highlights why more targeted research is necessary to help such cities prepare and adapt effectively.

3. Develop localised policy response to sea-level rise

Despite various national policy–based efforts for coastal management, there is a strong need for detailed local responses. India has been implementing efforts such as the Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM)—a holistic policy approach aimed at balancing environmental, economic, and social objectives in coastal areas. The ICZM calls for the integration of different sectors related to coastal areas, such as fisheries, tourism, urban development, agriculture, and maritime transport. It also aims to achieve coherence among public and private initiatives such as infrastructure projects, environmental conservation efforts, and community-based programmes.

While this is true on paper, the ICZM often does not capture the nuanced details specific to each region. The unique geography, infrastructure, and socio-economic factors of small coastal cities significantly influence their vulnerability to sea-level rise. For example, in Goa, unique flood management systems such as khazans (wetland areas with embankments) have been threatened by rising sea levels, which endangers these embankments and increases saltwater intrusion. Additionally, more frequent extreme weather events and altered rainfall patterns are disrupting the delicate balance of these ancient ecosystems, compromising their ability to manage floods and support traditional agriculture. Conserving these structures requires a deep understanding of local infrastructure and ecosystems so that tailored solutions that account for these unique factors can be developed.

However, the exclusion of localised knowledge on khazans resulted in the approval of projects that were impermissible in the protected areas. These included the construction of a bypass and cutting of 69 mangroves in these lands. The building of permanent columns in salt pans, which are critical to the khazan ecosystem, also points to a lack of integration of local knowledge in making critical decisions.

This gap extends to policy responses to sea-level rise, where traditional khazan management techniques have been overlooked. For instance, massive landfilling for development projects and the fragmentation of the ancient khazan system, carefully maintained by locals over the years, have been cited as major factors contributing to increased flooding in these areas.

4. Focus on citizen engagement and awareness building

Communities can play a crucial role in monitoring local environmental changes and providing valuable data. Grassroots initiatives, where citizens collaborate with local authorities to track sea-level rise or other associated climatic changes, can enhance data collection efforts. Organisations such as Architecture T in Goa and Sustera Foundation in Kerala have been involving communities for increasing awareness around many of these issues. Sustera, for instance, has been engaging with school and college students and empowering them to become ‘climate champions’ who lead local climate action initiatives. Similarly, there are ongoing efforts in Goa that convey vital information about the impact of climate change on khazan lands to locals, so that they can demand action from elected representatives.

Raising awareness about local climatic changes and about simple, actionable steps that individuals can take to protect their properties and local environments has the potential to significantly mitigate the impact of rising sea levels. Take the example of Murukesan T P, who has been actively involved in planting mangrove saplings along the coastline, recognising that they act as a natural defense against flooding. Environmental groups and local communities too have launched several projects such as Haritham Vypeen to create a ‘bio-wall’ of mangroves, aiming to plant 1 lakh trees over three years, with the support of volunteers and local residents.

The escalating threat of sea-level rise needs urgent and customised responses aimed at safeguarding India’s small and mid-sized coastal cities. While broad policy frameworks at the national level provide a foundation, they are often unable to consider the unique vulnerabilities of individual communities. Localised studies led by citizens, nonprofits, academics, and government organisations are essential to uncover specific risks such as the impact on drinking water quality, loss of natural coastal barriers, and economic disruptions in sectors such as fishing and tourism. Engaging local communities in monitoring and data collection can enhance the precision of these efforts.

Nimisha Samadhiya and Arundhati Chowdhary contributed to this article.

—

Footnotes

- Nagrika defines small and mid-sized cities as cities with a population of under 3 million according to the 2011 Census.

Know more

- Read the full report here.

- Read this analysis of state- and national-level policies on coastal climate risks in India.