India’s coal dependency is more complex than that of countries in the Global North. Amidst deliberations on coal phase-down and just transition planning and strategies post COP-26, the intricacies of this dependence make any phase-down a delicate and intense socio-economic and political process. Apart from the country’s reliance on coal for energy security, this dependency is also spread across economy, especially amongst coal communities.

Several studies have mapping coal reliance and its effects on states’ revenues, railway freights and fares, the economy of coal producing districts, as well as on industries such as transport, power, sponge iron, steel and bricks.

More importantly, accounting for the impact on livelihoods and jobs of coal communities are at the core of coal dependency discussions in the country. There are two approaches to examine coal labour in India. The first is to map direct, indirect and induced employment and the other is to study formal and informal labour in the coal ecosystems. However, these studies largely focus on the magnitude of labour dependency.

In India’s coal states, labour dependency on coal is hardly a one-generation phenomenon. Rather, this dependency is produced and reproduced in these regions across generations. A temporal perspective, premised on the principles of intergenerational equity, must complement the quantification of coal workers in the hierarchical labour structure of coal mines and designing appropriate ‘just transition’ policy interventions.

Generations of communities rely on coal for their livelihoods, across a range of occupations from formal work in the mines to coal scavenging. The nature of dependence may change over the years. A formal worker’s son may not remain a formal worker but would continue to draw livelihood from other informal employments linked to the mine. However, there is little structural change for more vulnerable groups at the bottom of the social hierarchy, such as Dalits and women. Due to their lack of land ownership, they remain entangled in precarious labour relations. The coal ecosystem continuously replicates social hierarchies of caste and gender and exacerbates socio-economic inequalities.

Two generations in Talcher

Manda, a village in the Talcher coalfields of Odisha, acquired for mining in the 1990s, illustrates these feature.1

The Talcher coalfields comprise nine mines–eight opencast and one underground–operated by Mahanadi Coalfields, a subsidiary of the public sector company Coal India (CIL). Spread over 3,53,360 acres, Talcher is one of the highest coal dependent regions in the country, measured in terms of coal mining jobs, pensioners, and expenditures under corporate social responsibility funding (Pai 2021).

In 1981, Talcher was primarily an agrarian society: 68.30% of the main workers were engaged as cultivators (Directorate of Economics and Statistics 1995). By 2011, just 6.4% of the population were engaged as cultivators and around 9% were working as agricultural labourers (Census 2011). The rest of the population, directly and indirectly, was dependent on coal and other coal-induced industrial settings for livelihoods.

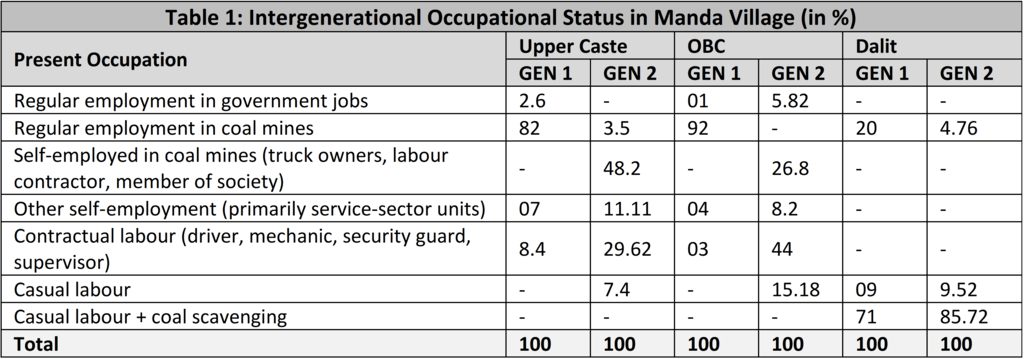

In Manda itself, households lost their agricultural lands, leaving them with just homestead land intact. In 2015, I surveyed a sample of 184 households (out of a total 720) by visiting the village settlement area and followed it up with fieldwork between 2018 and 2020. Around 18.17 % of this sample was from upper caste groups,2 61.48 % Other Backward Classes (OBCs), and 20.35 % Dalits. The Dalits were most marginalised in land ownership, occupation, and residential segregation.

To trace the intergenerational labour dependency, I focused on two generations in the village. The first generation had livelihoods directly affected during land acquisition and were beneficiaries of job compensation. The second generation comprised the sons of the first generation. These sons were in educational institutions during the acquisition process and entered the labour market later. Daughters were rarely nominated for any kind of compensation by their families, often leading to family disputes (Nayak 2020). A few daughters-in-law, though, had been offered jobs in the coal mines.

Two aspects of intergenerational labour dependency on coal are particularly noteworthy. First, coal communities across social groups rely on a range of formal-informal labour in the coal ecosystem, and this is not limited to one generation. Second, there is no structural transformation for the most vulnerable within coal communities. In the setting of the coal mines, Dalits and women, over generations, are at the bottom of the labour hierarchy and are hardest hit.

Amongst the General and OBC categories, more than 80% of the first generation were given formal jobs in the coal mines as compensation.3 By the next generation, though, with a decline in formal jobs, the majority of second generation General and OBC households earned livelihoods through contractual labour or self-employment in coal mines and elsewhere.

In the case of amongst first generation Dalit households, the majority of which were landless (see Table 1), just 20% received formal jobs. The rest drew their livelihoods from casual wage labour and coal scavenging. Second generation Dalits continue to depend largely on such avenues.

Between generations, labour dependency on coal intensified and expanded.

Many men in the age group 18-40 years old work as contractual workers in the mines–as drivers, guards, or supervisors–and earn Rs 15,000–20,000 wages per month. These informal occupations lack the social protection that regular employment offers—better wage agreements, social security, and strong unionisation. Young contractual workers in Manda aspire for formal jobs like their fathers’. Santosh, a 25-year-old local man from an upper caste household, works as a contractual mechanic in the mines. He says “I deserve a formal job, justifiably so, as a compensation to land–an asset transmissible to generations. We hope we will get it in the near future, as soon as my father, who is a formal employee in the coal mines, arranges an alternative route to the job–by buying land in a village where land is to be acquired soon.”

Others are self-employed, running small businesses catering to the mines, such as operating a truck or working as a labour contractor, earning Rs 40-50,000 per month. For various informal works of the coal mines, such as civil and construction, security, and mechanical purposes, many contracts are offered each year to various local contractors. Some contracts like the road sales of coal through truck transportation are highly remunerative.

Casual wage employment under labour contractors and coal scavenging secures Dalits’ present and future.

Intergenerational labour dependency amongst Dalits is structurally different from other social groups, but it remains embedded in the coal ecosystem. Casual wage employment under labour contractors and coal scavenging secures Dalits’ present and future. They work in construction, coal washeries, coal loading, sweeping at offices, and other manual labour, earns Rs 200–250 per day. They scavenge from small and shallow mines, abandoned coal mines, or from the coal that falls off trucks and trains coming from the larger mines. On an average, workers scavenge 50 kg to 100 kg, selling it on bicycles and bikes by to households, motels, brick kilns factories, small shops, and to the coal mafias.

Women’s labour is marginalised and invisible. They are underrepresented in formal coal jobs (Nayak and Swain 2023) and are engaged in unpaid, underpaid, devalued, invisible, and precarious labour (Nayak, 2022). In Manda, more than 90 % of women from upper caste and OBC households were engaged in unpaid social reproductive work. Half of the Dalit women were restricted to domestic duties. The other half was triply burdened with social reproductive work, casual wage labour, and coal scavenging (Nayak 2022). These patterns were consistent across both first and second generations. In the absence of targeted policy interventions, such an exclusionary path dependency for women’s labour will continue to be reproduced in coal ecosystems.

Longing for just transformation

Discussions exploring the aspirations, perspectives, and the role of youth in the coal regions are necessary steps towards bringing out diverse voices from the grassroots. However, as things stand now, they are distant from the larger question of coal dependency.

Intergenerational labour dependency on coal makes coal communities in India extremely vulnerable in the energy transition. Whether the phasedown of coal is immediate or decades away, breaking the coal mono-economy and intergenerational labour dependency by generating alternative livelihoods and skills would potentially reduce the risks to communities.

But mere reskilling programmes would not achieve the agenda of transformative justice and intergenerational equity, unless the generational aspects as seen in Manda are factored in.

One such step is to plan and design economic diversification of coal ecosystems–an effective mitigation strategy rather than adaptation response to shocks. This calls for ensuring social transformation at two scales in just energy transition: diversification of livelihoods away from coal for communities and occupational mobility for most vulnerable groups within the communities. It is essential to develop a long-term vision of a just transition for coal districts and address the coal mono-economy and its consequential impact in the form of intergenerational labour dependencies on coal in these regions.

(The author is very grateful to Ashwini K Swain for his feedback. Responsibility for the information and ideas presented here rests entirely with the author.)

This article was originally published on The India Forum.

—

Footnotes:

- Manda is a pseudonym to anonymise the village.

- Historically, the village was divided into different castes. They included General category castes (Brahmins and Kshatriya, upper castes), OBCs (primarily Chasha, middle ranking peasant castes), and Scheduled Castes/Dalits. This caste division has shaped the landownership, occupational hierarchy and residential patterns in the village.

- The compesation was as per CIL policies and Odisha’s Rehabilitation and Resettlement (R & R) Policy of 1989.