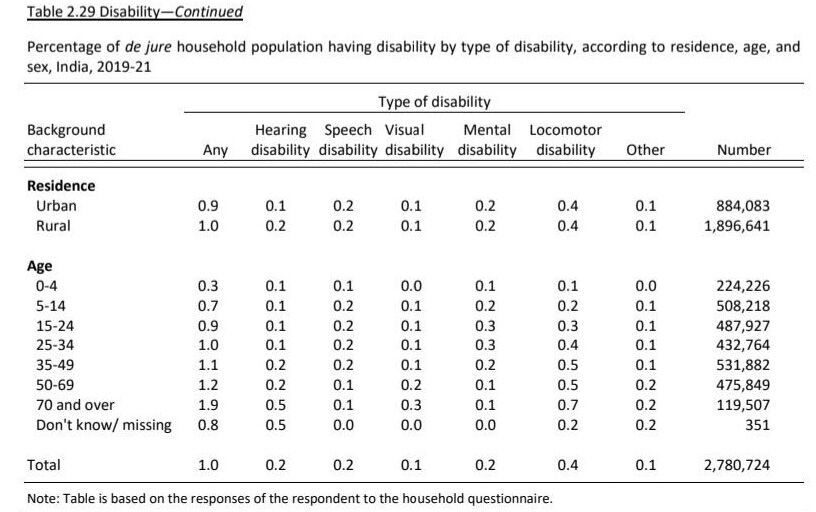

If data from the latest National Family Health Survey (NFHS) are considered, India’s population of people with a disability has reduced to 1% between 2019 and 2021, from the 2.2% (26.8 million) estimated by the Indian census in 2011, and also from the 2.2% estimated by the National Sample Survey Report in 2018.

The difference between the estimates can be traced to the different approaches of the surveys. The NFHS 5 focuses on the ‘de jure’ definition of disability, focusing on counting only people with benchmark disabilities under five broad categories. In contrast, Census 2011 had a broader definition of disability focusing on self-identification, while the 76th round of NSS (2018), which was about counting those with disabilities, covered all disabilities under the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016 including rare disabilities.

Globally, 15% of the world’s population has a disability, as per the 2011 World Report on Disability from the World Health Organization.

Overall, there is no accurate estimate of India’s population of disabled persons because all surveys only capture a part of the population, experts say. Given the lack of reliable estimates, other methods that are not designed as such, but could be used as proxies to count the disabled, include disability certificates or the newly introduced Unique Disability ID. But these only cover a small part of the population, data show and experts say.

The issue of counting persons with disability has a relationship with the quality of the lives they live. For instance, most welfare schemes, from free assistive devices to reservation in government jobs, and programmes for the disabled are built around certification. Knowing the population of those with disabilities is also important as it determines how much money is allocated by states for the monthly disability pension.

Further, the NFHS could have illuminated the specific health issues of India’s population with disabilities and their access to nutrition and healthcare, but instead, its methodology raises doubts on the way it counts those with disabilities.

An analysis of the methodology of surveys, expert opinion, and inputs from those with disabilities shows that to understand the true population with disabilities, and make sure they are not excluded from social welfare as well as from being counted, survey organisations should consult disability experts and disabled people while the survey is being designed, extensively train and sensitise surveyors on disability (as in 2011 Census) and at least include all categories of disability that are covered in the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016 (as in 2018 NSS).

Why the NFHS estimates are lower

Censuses from 1872 to 1931 asked about disability, but the question was not included in censuses from 1941 to 1971, and in the 1991 census. The census collected information on three kinds of disability in 1981 and on five types of disability in 2001. Years of advocacy by disability rights groups and activists led to questions related to eight kinds of disability being added in the 2011 census.

The fifth NFHS between 2019 and 2021 was the first time that questions related to disability have been included in that survey. Questions capture five types of disability–locomotor, visual, hearing, speech, mental–and an ‘others’ option, a step back from the eight counted in the 2011 census, and much lower than the 21 recognised by the Rights Of Persons With Disabilities Act. Persons with intellectual and learning disabilities, and those with chronic neurological conditions and blood disorders, have not been mentioned as a separate category despite their specific needs and vulnerabilities.

The NFHS says that their estimate is of ‘de jure’ persons with disabilities, which means those disabled, according to the law.

Experts say that counting the disabled only ‘de jure’ can be a problem. “If you are a person with a disability, nobody can discriminate against you. Any kind of discrimination–and that can happen with a limp, it can happen with stutter. In terms of social exclusion, these things matter,” said Dhanda. “When we talk of full participation [in society], how can we only count people ‘de jure’?”

It is unclear what ‘de jure’, according to the NFHS means, and it could mean those who are certified as having a disability. But, the NFHS does not consider the certificate to identify those who have a disability. Instead, the manual asks the interviewer to explain to the respondents what makes a person disabled, for which it provides prompts to help respondents identify a person with disability in the household.

The NFHS has three questions about disability in the questionnaire.

a) Does any usual resident of your household including you have any disability?

b) Please tell me the names of those persons.

c) For each person with a disability ask: What type of disability does this person have? Any other?

“NFHS has a well-defined system for inclusion of new dimensions/questions on the request of various departments,” said S.K. Singh, professor and head of the Department of Survey Research and Data Analytics at the International Institute of Population Sciences (IIPS) that designs and implements the NFHS. This time, the Department of Social Justice and Empowerment asked that disability be added to the NFHS, he said.

New additions are discussed “thoroughly” in a Technical Advisory Committee, and examined during pre-testing, he further explained. “We tried to question the reliability and validity of the responses without a [disability] certificate.”

The questions were meant to capture certification-based identification, but without the actual certificate, and the way was to ask questions which help identify a person with benchmark disabilities (above 40% impairment), which is ‘de jure’ for getting most entitlements meant for those who have a disability. We have asked Mr Singh of IIPS for further clarification on how the NFHS defines ‘de jure’, and will update the story when we receive a response.

“Ultimately it was decided to include (disability) and then we adopted a simplified version of the questions following DHS [Demographic and Health Survey] protocols implemented across 92 countries,” Singh said.

But the DHS questions are broader than the NFHS. The DHS introduced an optional disability module in 2016, and defines disability, as “an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions”, and its own questionnaire asks respondents about the level of difficulty they face: no difficulty, some difficulty, a lot of difficulty, cannot do that task (seeing, remembering, walking etc.) at all, and don’t know. It includes vision, hearing, communication, remembering/concentration, movement, daily functions (washing and dressing) and interacting with others.

This is different from the Indian NFHS in which certain levels of impairment are not classified as a disability. For instance, “persons with proper vision in one eye (one eyed persons) will not be treated as visually disabled”, the NFHS says.

The census too does not consider a one-eyed person as disabled, but its criteria are broader than that of the NFHS.

The guidelines issued by the government, for example, say that one of the criteria for people to be classified as low vision, is “limitation of the field of vision subtending an angle of less than 40 degree up to 10 degree”. For the common man, it is unlikely to know these technicalities and self-report as a person with low vision, which might lead the NFHS to miss a part of the population with a disability.

The census too does not consider a one-eyed person, and someone who has a hearing problem in one ear, as disabled, but its criteria are broader than that of the NFHS. For instance, in helping identifying people with disability in seeing, the manual instructs that people who “can see light but cannot see properly to move about independently; or have blurred vision but had no occasion to test if her/his eyesight would improve after taking corrective measures” are also identified as a person with disability.

The census 2011 tested a question on whether a person was partially or totally disabled, but was dropped because the “response was not encouraging”, according to a presentation by the office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India.

“The law is distinguishing between just a person with disability, person with benchmark disability, person with severe disability, person with high support needs; so there is a continuance in the law. When you are doing a count, you necessarily need to begin with the lowest,” says Amita Dhanda, Professor Emerita at the National Academy of Legal Studies and Research (NALSAR). “You can’t take the higher point and say we will only count them.”

We reached out to the Chief Commissioner of Disabilities, under the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, of the Indian government to ask whether they were consulted about the process of including disabilities in the fifth NFHS and if they would like to comment on the methodology and findings of the survey. We will update the story when we receive a response.

Certification and stigma

The Indian government ‘certifies’ a disability. But, for any survey, considering a disability certificate as evidence of disability would not work. Disability certification is very technical and depends heavily on the medical model of disability (which emphasises an individual’s physical or mental deficit, rather than a social model of disability, looking at the barriers they face), and requires a variety of documents and medical examinations.

The benchmark disability, measured in terms of percentage (level) of impairment, is essential to access any welfare scheme meant for the disabled. For example, according to the guidelines by the Ministry of Social Justice for the assessment of various disabilities, if your fifth toe is amputated you are only 1% impaired, if your first toe is amputated you are 10% disabled and if you have lost all your toes, your percentage of impairment is 20%.

These technicalities lead to the very ableist objectification of disabled bodies, and can lead to harassment when a person with a disability wants a certificate.

Twenty-five-year-old Alice Abraham, a student in Kerala, had been losing her eyesight, slowly, over time, for almost eight years, because of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. In 2020, she realised she would not be able to write her university exams without someone assisting her in writing it, and she decided to get a certificate of disability.

To be allowed to come with a person who writes the exam for you, your ‘percentage of disability’ needs to be at least 40%, the benchmark required for most accommodations if you are a person with disability under one of the eight categories recognised by the Right Of Persons With Disabilities Act, 2016.

Abraham had lost complete sight in one eye and was losing sight in the other, so it should not have been a problem for her to get a certificate. But when she reached the district hospital, the doctor said they were doubtful if she was eligible for a certificate. Abraham said: “The medical officer said that these days many, especially young people, are getting disability certificates for getting jobs easily.” The doctor then added: “I can only put 40%. If you want a higher percentage [of disability], you should go to the general hospital for evaluation.”

Not everyone chooses to get a disability certificate, partly because of the stigma attached to it. Abraham’s parents too did not want her to get a certificate, she said.

Notwithstanding the other trials that a person with disability faces, the process of certification of the disability is in itself an examination, one in which the likelihood of failure is extremely high, no matter what disability and what percentage of impairment. In this process, the person with disability also faces harassment, loss of dignity and questioning by others.

Insensitive process

The Unique Disability ID (UDID), launched by the government in 2016, would help create a national database for persons with disabilities, “encourage transparency, efficiency and ease of delivering the government benefits” and for “stream-lining the tracking of physical and financial progress” of beneficiaries at all levels.

But this has only made the process more complex. Not only do many disabled people have to again appear in front of a medical board to get a UDID, but despite already having a disability certificate, the process also requires people to visit hospitals and get medical tests done.

Shivangi Agrawal, a 30-year-old artist and disability consultant, started learning to drive a modified vehicle a year ago as her legs and hands had been affected due to a congenital disability. Learning how to drive was both an empowering act and a key to independence in a city like Delhi, said Agrawal. But to get a driving licence in Delhi, she had to now get a UDID, along with the disability certificate she already has.

She went to the local government hospital in East Delhi to get that certificate made where she had to run from pillar to post to get the approvals and had to get medical scans done, such as X-Rays and CT Scans. When she submitted all the documents, she was sent to a physiotherapist who tested her body movements and gave her a percentage of impairment of around 70%. She was then asked to return a day later, this time to appear in front of a medical board which consists of specialist doctors.

The doctors who were part of the medical board again tested her body parts and told her to walk. The entire process was traumatic for her and the doctor kept talking to her rudely and told her they would only talk to her parents, the 30-year-old said. “They kept ‘testing’ my body parts and would not answer my questions. Whenever I asked questions, they got angry. It was like ‘how dare you ask me anything?'” And then they changed the percentage of impairment to 89%. When Agrawal asked for clarification on this percentage of disability, the doctor refused to talk to her, she said. “The certification turned into an episode of harassment and trauma that took a toll, physically and mentally.”

The situation is worse in rural areas, and depending on the caste, class and gender. Only 28.8% of those with a disability have a disability certificate, as per 2018 data from the National Sample Survey. The survey found that 2.3% of the rural population and 2% of the urban population had a disability.

Counting disabled people

I, too, fear getting a UDID, even when I already have a disability certificate. I was born with a rare disorder, VATER Syndrome, that has resulted in lifelong disability and illness. The moment I applied for a disability certificate, I was made to feel that I was merely a beneficiary in search of entitlement. During the entire process, neither the doctors nor the health system displayed any empathy for me, nor was the system transparent. One would assume that getting a UDID for those who already possess a disability certificate would be easy, but yet you have to physically visit the nearest medical centre, and depending on the discretion of the medical officers, might have to appear in front of a medical board again. Unless it’s absolutely necessary, people like me would opt out of the process.

This underlines the point that counting the disabled, as in through a survey, has to be seen as separate from the issue of counting disabled people, when seen in terms of their quality of life and their participation in society, as even those who do not have benchmark disability may face different forms of discrimination.

“The right of non-discrimination is available to every single person with disability; [it] doesn’t matter what the severity of disability is. And that’s where self-identification makes sense. Even if it’s little things–you have lost one eye or have a stutter or general visual acuity is affected, even if you are getting a treatment, you can be discriminated against,” said Dhanda.

This article was originally published on IndiaSpend, a data-driven, public-interest journalism nonprofit.