India’s micro-, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) sector plays a vital role in the country’s economy, contributing to approximately one-third of its GDP. A majority of the sector, approximately 99 percent, constitutes of micro-enterprises, classified as those with investments of up to INR 1 crore and a turnover of up to INR 5 crore. The sector also includes small enterprises, with investments of up to INR 10 crore and a turnover of up to INR 50 crore, and medium enterprises, with investments of up to INR 50 crore and a turnover of up to INR 250 crore. However, micro-enterprises seldom expand or convert into these small or medium enterprises, leading to a phenomenon known as the ‘missing middle’.

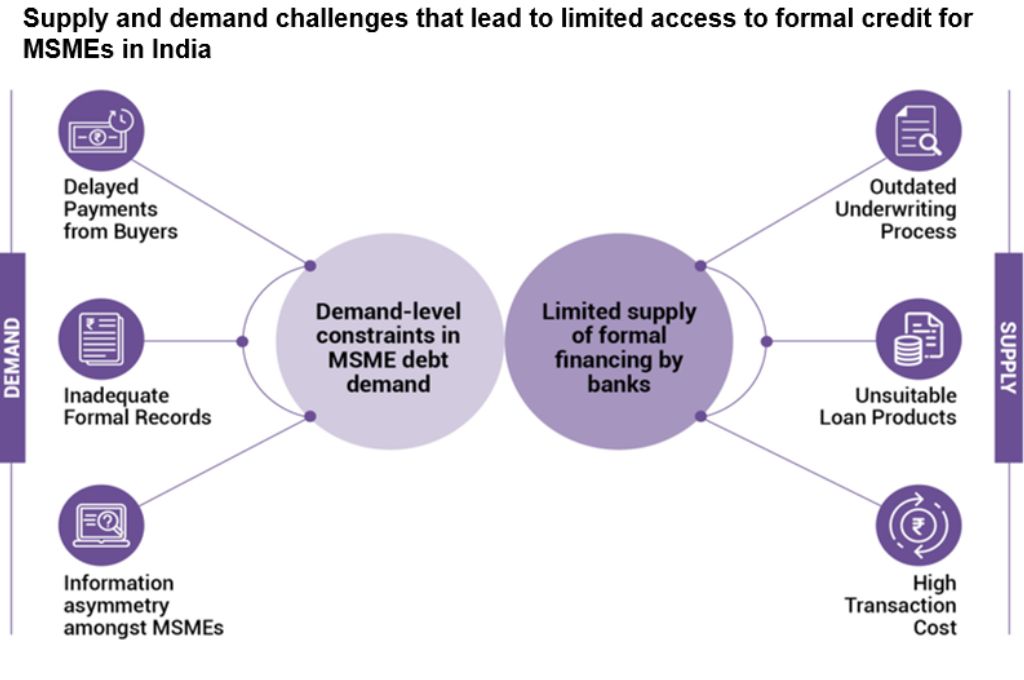

This is primarily because micro-enterprises are unable to access credit to grow their operations due to traditional loan processes, which rely on MSMEs demonstrating their creditworthiness through collaterals such as evidence of digital financial transactions and property. Their limited access to affordable formal credit results in poor working capital reserves, impeding their productivity and thwarting their expansion into mid-sized enterprises. This concerning phenomenon in turn hampers the overall economic growth of the country.

Cash flow–based lending could solve this critical credit gap

The cash flow–based lending approach could prove to be a viable alternative for MSMEs, especially micro-enterprises. Unlike traditional lending methods, this approach focuses on a borrower’s projected future and past cash flow data to determine their creditworthiness. This form of lending forms the core of India’s Open Credit Enablement Network (OCEN), an open protocol infrastructure that has the potential to democratise and transform India’s digital lending landscape and address the persistent challenges of the MSME credit gap, estimated to be at a staggering USD 800 billion.

An emerging digital public good being developed by Indian software industry think tank iSPIRT, OCEN streamlines the process of lending and borrowing by connecting a wide range of stakeholders in the lending ecosystem. Using the cash flow–based lending approach, it enables borrowers to share their data digitally, eliminating the need for traditional collateral requirements.

This makes it viable for previously unbanked and underbanked micro-enterprises to access credit through OCEN.

The implementation of OCEN depends on a diverse group of stakeholders, wherein each of them plays a unique role within the intricate lending infrastructure, bringing distinct expertise and performing specific functions. This includes:

- Loan service providers (LSPs): Consumer-facing digital platforms—web- or application-based—that provide low-cost distribution, bringing knowledge of local and customer contexts to the network.

- Technology service providers: FinTech companies that support onboarding to the OCEN protocol, roll out tailored credit programmes for MSMEs, and aid in technical implementation and adoption.

- Account aggregators: Data intermediaries that act as consent brokers, allowing lenders quick access and plugging in of critical digital infrastructure for lending.

- Underwriting modelers: Entities that assess vulnerability in terms of non-payment and late payment, supporting the decoding of raw data signals captured through digital trails.

- Lenders: Banks, NBFCs, and small finance banks that provide capital and access to core banking networks, utilising the LSP infrastructure to increase last-mile connectivity and provide tailored credit solutions.

- Borrowers: MSMEs or individual consumers who leverage credit options available within the LSPs’ platforms through secure digital processes, getting connected to multiple lenders through one platform.

Why should lenders opt for OCEN?

The adoption of OCEN could unlock substantial economic potential for the country. By 2023, MSME digital lending has the potential to increase by 10–15 times to reach INR 6–7 lakh crore (USD 80–100 billion) in annual disbursements. While OCEN makes a strong case for borrowers to be a part of the network, lenders too have a major incentive to join.

- By capturing data digitally and doing away with the manual filling of forms, OCEN helps simplify the lending process. This enables lenders to offer customised loan products based on specific needs such as time, repayment schedule, and interest rates, benefitting both lenders and borrowers.

- OCEN allows lenders to monitor the finances of the borrower in real time, helping them identify early warning signs for potential defaults. It automates key workflows such as loan disbursement and repayment tracking. Additionally, OCEN optimises the risk assessment process by enabling borrowers to share their data from various sources through consent-driven mechanisms without any in-person visits. This allows lenders to access and evaluate comprehensive, up-to-date credit histories, enhancing the efficiency of their evaluations. This makes it economically viable for formal financial institutions to underwrite low-cost, timely, and small-sized loans to the historically unbanked and underbanked, including micro-enterprises.

- OCEN unlocks a large potential customer base of 190 million micro and small enterprise that lenders otherwise wouldn’t have access to. The operational efficiency of the process, when paired with the prospect of a diversified loan portfolio that OCEN will offer, makes small-ticket lending possible. This will enable lenders to expand their market reach and loan volumes.

- By integrating with already-scaling account aggregators, OCEN can enable improved credit risk assessment, especially crucial for lending in the informal sector that constitutes approximately 40 percent of MSMEs.

However, while OCEN is a step in the right direction, it faces several challenges that can potentially restrict its popularity and viability.

1. Digital readiness and infrastructure

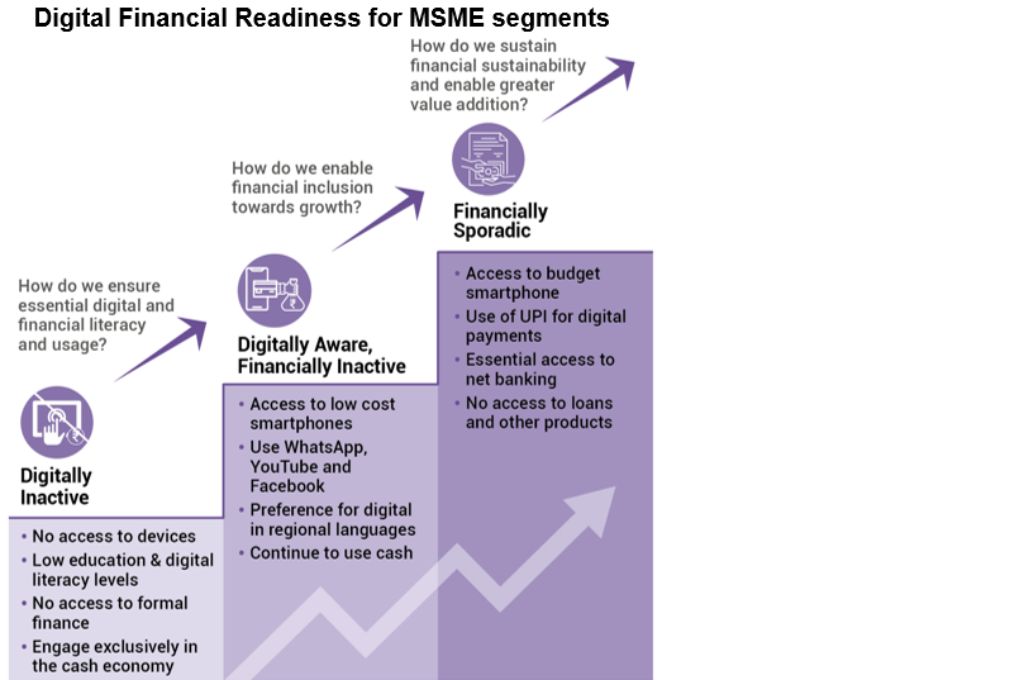

The effectiveness of OCEN depends on the degree of digital expertise possessed by micro-enterprises. For both lenders and borrowers to actively participate and avail the benefits of this credit system, it is imperative that MSMEs have digitally captured expenditures, income, and investments, also known as digital financial trails. These are imperative to determine a borrower’s eligibility for credit. An absence of these would render obsolete any incentive for lenders to participate in the model.

However, more than 90 percent of India’s population lacks basic digital literacy skills. In the MSME sector, the spectrum varies drastically, with some being completely unfamiliar with digital financial products while others use digital banking and transaction mediums such as UPI regularly. For instance, while approximately 33 percent of micro- and small enterprises are increasingly conducting their business on social media platforms, 60 percent of MSMEs are only beginning to move from cash to digital payments, indicating early stages of adoption.

In addition to this, even when digital literacy is present infrastructural shortcomings such as unstable electricity, sparse mobile tower coverage, and intermittent broadband connectivity limit the usability and reliability of digital tools, particularly in rural India.

An in-depth evaluation of the readiness of India’s micro-enterprises to adopt this new infrastructure is essential to ensure that the benefits of OCEN are within their grasp and align with the country’s financial inclusion agenda.

2. Cash-based economy

Even though OCEN makes it viable for financial institutions to underwrite low-cost loans for underbanked or unbanked MSMEs, the large number (an estimated 190 million people are unbanked or without formal bank accounts) is still an obstacle. In addition to this, approximately 72 percent of transactions in India are cash-based. India’s cash-based economy, along with a significant number of informal MSMEs, poses a considerable challenge to OCEN adoption. Without formal banking channels, MSMEs lack bank records and digital financial traits required by OCEN. The absence of formal business registration and records further limits accessible and reliable data for OCEN. This prevents MSMEs from establishing digital creditworthiness, which is crucial for OCEN adoption.

3. Data privacy

Even when digital readiness and formal banking channels are present, data privacy arises as an obstacle to the widespread application of OCEN. The OCEN framework relies on sharing sensitive financial information and personal data, leading to concerns about potential data breaches and misuses such as created and marketed tailored products based on financial information and size of the company by various agencies. As the volume of loan data increases, cybersecurity will become an increasingly big challenge, especially in the absence of any law on data protection in India. Including stringent measures such as encryption, secure storage, and strict adherence to privacy regulations can help combat this. Embedding privacy in design, and respecting user privacy, is equally essential.

4. Apprehension among MSMEs

Transitioning to a digital platform is plagued with apprehensions and scepticism for the enterprises. Concerns around control, taxation, and transparency often prevent MSMEs from shifting to digital transactions. Since OCEN also calls for high transparency, there is concern among MSMEs about its potential consequence. Compilation of defaulter lists—those who are unable to pay back the loan in a timely manner—by OCEN also adds to this reluctance, and could lead to the exclusion of these individuals from the lending process. To address this, a large part of onboarding must focus on creating awareness about the network, and helping stakeholders understand its benefits. This can be done by leveraging networks of first movers and risk takers, and by incentivising MSMEs looking for lending through formal channels. Policy and regulations must also be relaxed to quell the anxieties of the stakeholders being onboarded.

Bridging the gap of the ‘missing middle’ in India’s MSME sector is both a significant challenge and an enormous opportunity that necessitates systemic transformation in lending approaches. OCEN emerges as a promising solution by leveraging digital data, reducing costs, and enabling better loan offerings. However, success hinges on MSMEs’ readiness for digital transformation and the cooperative and trusting relationship between the OCEN ecosystem and MSMEs. Achieving this collaboration can unlock a new era of financial inclusion, unleashing untapped economic potential and fuelling nationwide growth.

—

Know more

- Learn more about how OCEN can enable small and marginal farmers.

- Read this article to learn more about how technology can drive financial inclusion.

- Learn more about digital solutions of India’s financial landscape.