The majority of the 240 million children with disabilities worldwide live in low- and middle-income countries such as India, where services for them are inadequate. Two decades ago, Ummeed was founded to address this huge gap.

Since we were a team of paediatricians and therapists, Ummeed started as a clinic that offered diagnosis and therapy to children with diverse visible and invisible disabilities. Over time, however, we realised that our understanding of disability as a medical deficit was fundamentally flawed, and so were our attempts to fix it.

If we viewed each child as unique, and considered disability as a part of neurodiversity among children, we could begin to work towards the outcomes that we hope for all children—going to school, playing cricket, creating art, and having fun with friends and family.

It is important to recognise that children with disabilities may never become ‘normal’ and yet have a right to do the things that other children do. Thus, our key metric of success should be participation in activities at home, school, and the community, and not merely academic achievement or an increase in vocabulary or IQ. Recognising this led us to work with not just the child but also the entire ‘village’ that contributes to raising the child, including the family, school, community, and other systems. Unfortunately, most parts of India are not ready for this kind of thinking, and the reasons for this are many—lack of awareness, knowledge, skills, and policies, among others.

Approximately two years ago, we decided to use a grant from Azim Premji Foundation (APF) to try and change the various systems that impact outcomes for children with and at risk of disabilities—in three pilot geographies of India.

The systems change framework we used

Social Innovation Generation (SiG) Canada defines systems change as ‘shifting the conditions that are holding the problem in place’.

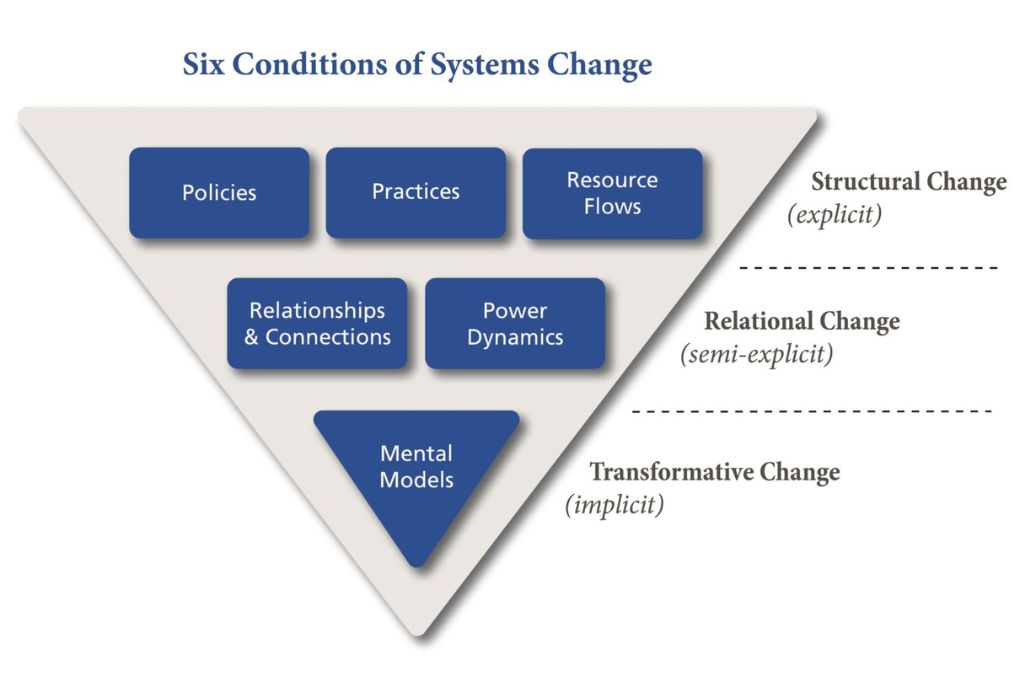

The Water of Systems Change, a 2018 paper by FSG in which they specify a systems change framework, describes three categories of conditions that need to be influenced for systems change to take place:

- Structural changes, which are explicit and therefore easy to influence and measure.

- Relational changes, which are semi-explicit and harder to influence and measure.

- Transformative changes, which are deeply held beliefs and assumptions (mental models) that are implicit and the hardest to determine, but which last the longest.

According to FSG, shifts in system conditions are more likely to be sustainable when working at all three levels of change: implicit, semi-explicit, and explicit. Below we share our experience of working at these three levels over the last two years.

But we should perhaps start with a disclaimer. For now, we may best be described as aspirational systems changers who are trying to understand how to bring about such a shift. However, we do believe that our learnings can be useful for others, and it is with this hope that we share our journey here.

1. Transformative changes: Working on mental models

When we started this project, we were not aware of the framework created by FSG but intuitively focused on changing the mental models of disability. Mental models are deeply ingrained habits of thought that frame how we do things. Typically, mental models are the hardest to shift and hold the problem in place. Therefore, they are key to address in ecosystem change efforts.

We were clear about our mental model of disability—that it is a condition that involves the child and the environment and the ways in which they interact, rather than a medical deficit or problem. We therefore chose partners who were fundamentally aligned with this ideology even if they had not articulated it as such. We further facilitated their understanding of this with training sessions, tools, and ongoing support. An example is the training we offered in partnership with CanChild Canada on the PREP approach, which helped participants understand how environmental factors need to be changed to help children participate in activities. Here, children and families get to identify for themselves which environmental factors need to change.

After the training, the Ummeed team organised multiple discussions where participants put forth ideas on how this approach could be implemented in their settings. Currently, at least two of our partners—a community-based disability organisation and a paediatrician—are incorporating the PREP approach and participation-based outcomes in their intervention model.

2. Relational changes: Working on power dynamics and relationships

For systems change to take place, different stakeholders have to be brought together so that they can work towards common outcomes. The stakeholders that children with disabilities and their families have to interact with, and whose services they depend on, include at a minimum the healthcare system, the education system, and the government. These parties have never traditionally had to engage with each other, which creates interesting opportunities and challenges.

Shifting the power dynamics: For childhood disability, the stakeholders that hold more power are institutions of healthcare, education, and the government. Children and families on the other hand are the least empowered but the most invested in the outcome. They have, therefore, the greatest incentive to be changemakers. We recognised that there were power dynamics at play that we needed to help shift. As a team of doctors and therapists, we acknowledged that we ourselves had not lived through experiences of disability and exclusion, and probably had our own biases. This led us to work closely with parents as well as disabled youth, who now act as advisers to us and are beginning to inform our work. Further, we did baseline studies with our partners to understand the local, on-ground situation vis-a-vis parent empowerment and voices, and used this to drive our actions. In one of our geographies, for example, we found that parents were not even being invited to observe their child’s therapy session, let alone being consulted on goals for their child. To start shifting this, our partners started a social media campaign called #openingdoors/#opendoorpolicy, which has professionals and parents speaking up in support of the need for parents and caregivers to be inside the therapy room.

Facilitating connections: While it is a given that stakeholders should work with each other towards common goals, it is easier said than done. We have been looking for opportunities where stakeholders have a natural reason to work with one another because their activities are complementary. The group of partners that collaborated on the social media campaign also brought together a cohort of schools for a sensitisation drive on inclusion in the school setting. This led to the implementation of a year-long in-depth training programme for a sub-group of teachers from these schools. Elsewhere, a paediatrician partner initiated the first-ever parent support group for caregivers of children with disabilities. Another paediatrician partner started referring families to a caregiver-run partner organisation to help them understand their rights. All of this, however, has been an uphill task and requires enormous effort—regular one-on-one calls, regular group calls, and intermittent group meetings.

3. Structural changes: Working on practices, policies, and resources

Structural changes such as changing practices and policies and bringing in resources are relatively easy to execute and measure. As part of the APF grant, we initially conducted a needs assessment with our partners to help identify their individual and collective needs. Some common themes emerged, such as challenges in acquiring and retaining trained resources, inadequately articulated organisational policies, and traditional tenets of expert-driven services being reflected in service models and practices.

Changing practices: As an organisation we have moved from providing clinical services alone to training and capacity building as a pathway to scale. Our training programmes, therefore, have been structured to provide knowledge and support change in behaviour and practice over time. In parallel, we worked with our partners on how they could use their influence to take their learnings to a larger group of stakeholders. Thus, one of our paediatrician partners, a state committee member of the Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP), helped introduce a statewide training curriculum on monitoring and supporting the development of high-risk newborns to enable early identification and intervention.

Building policies: Our workaround policies have largely been driven by partner organisations’ readiness to address issues at the local level. We helped two partners implement family-centred care as a key policy for their organisations. We believe that once parents are empowered, geography-level policy changes will follow.

Enabling resource flow: Many of our partners have required leadership support and competency support for middle management, funding, monitoring and evaluation, etc. Ummeed has been providing this support in addition to offering technical expertise, but in the future we may pull in other organisations to supplement our technical support. We were fortunate to get a donor who was value-aligned, willing to see this as a learning grant, and open to learning with us. However, only a handful of donors take such a systemic approach towards childhood disabilities. In such a scenario, organisations in remote geographies or young organisations find it hard to be self-sustainable, which is a criterion many donors set for prospective grantees. Since donor grants are the only resources that might exist in remote areas, such organisations are in critical need to be supported and nurtured.

Addressing the needs of children with disabilities is a complex social issue with no easy answers, as is true for many other social challenges. To institute implicit, semi-explicit, and explicit changes, we need to work with local partners, who know their own communities best. The initial outcomes, especially the implicit and semi-explicit ones, may be hard to measure and quantify for several years. In addition, our successes are often tied up with our partners, who may not acknowledge our role. However, the opportunity for constant learning and the possibility of driving systemic change can be great motivators for social purpose organisations.

—

Know more

- Read this article to learn how using a social justice framework for systems change planning can help leaders address the root causes of social problems.

- Read this article to learn more about the ecological systems theory, which sees child development as a function of many levels of a child’s surroundings.

- Read this article to understand how working within existing systems can help tackle problems.