School closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic have had a devastating impact on the education of children who attend government schools. It is estimated that 82 percent of primary school children in government schools have lost foundational abilities in math, and 92 percent have lost language abilities. This is a major problem given that nearly 10 crore children (approximately 40 percent of the 26 crore schoolgoing population) are enrolled in government schools at the elementary level (Grade 1–8).

Moreover, due to a loss of livelihoods and income, lakhs of migrant labourers working in cities have returned to their villages. With continuing uncertainty of livelihoods in cities, many workers are likely to enrol their children in rural government schools, making the situation even more challenging. In fact, a government school enrolment drive in Bihar in 2020 saw that nearly 11 percent of the 12.3 lakh children enrolled were from migrant families.

As schools start to reopen across the country, we need to ask: Are government schools equipped to respond to these fresh challenges? The answer is no, in no small part due to a shortage of teachers. Even before the pandemic, a large proportion of government schools had an adverse pupil–teacher ratio (PTR) at the elementary levels. This means that the number of enrolled pupils per teacher for primary (1–5) and upper-primary (6–8) levels exceeds the limits mandated by the Right to Education (RTE) Act 2009. In other words, these schools have a deficit of teachers. The puzzling fact is that these shortages exist despite India having more than enough government schoolteachers to fulfil the RTE-mandated PTR norms.

Unpacking the PTR puzzle

A healthy PTR is recognised as a necessary condition to ensure quality school education. The RTE Act 2009 emphasises that all schools (government, aided, and private) must maintain a PTR of not more than 30 and 35 pupils per teacher at the primary and upper-primary levels respectively. It also stipulates certain teacher allocation rules. For example, at the primary level, two teachers are required in a school with 0–60 pupils, three teachers for 61–90 students, and so on.

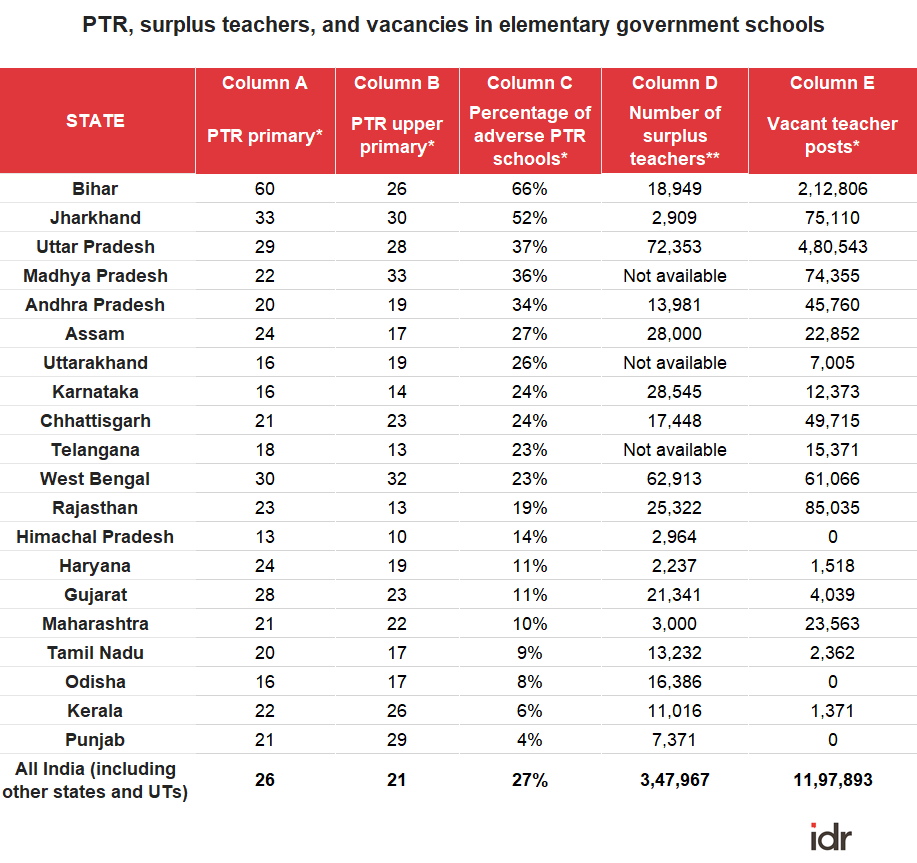

At the national level, India had an average PTR of 26 pupils per teacher at the primary level and 21 at the upper-primary level (Columns A and B in Table 1) in 2019–20. Both figures are well within the RTE-mandated limit, indicating that India has more than enough teachers to meet the PTR requirements. However, this average hides the fact that 27 percent of government schools have an adverse PTR at the elementary level (Column C).

Statewise data adds to this puzzle. Nearly all major Indian states maintain an average PTR that is well below the RTE-mandated limits of 30 and 35. Only in the states of Bihar (66 percent), Jharkhand (52 percent), Uttar Pradesh (37 percent), Madhya Pradesh (36 percent), and Andhra Pradesh (34 percent) is the percentage of schools with an adverse PTR higher than the national average.

It is interesting to note that states with lower PTRs on average can still have a large percentage of schools with adverse PTRs. For instance, the states of Uttarakhand, Karnataka, and Telangana have low PTRs at the elementary level, yet nearly a quarter of their schools have an adverse PTR. In comparison, Gujarat has higher average PTRs, but only 11 percent of schools with an adverse PTR. This clearly highlights the fact that a healthy average PTR at the state level is not enough to ensure an equitable distribution of teachers across schools within the state.

This paradox is compounded when we look at the coexistence of surplus teachers and teacher vacancies in several states (Columns D and E). A surplus teacher is one who can be counted as ‘excess’ after factoring in the RTE-mandated teacher allocation rules. Therefore, removing surplus teachers from a school will not lead to an adverse PTR for that school. In 2019–20, India had approximately 3.5 lakh surplus teachers who could be reallocated to other schools with vacancies. For example, Uttar Pradesh has nearly 5 lakh vacancies, which can be filled by reallocating its 70,000+ surplus teachers. In fact, states like Assam and West Bengal can fill all their vacancies by reallocating existing surplus teachers.

Understanding the inequitable distribution of teachers

Why do so many states, despite having more than the required number of teachers to fulfil RTE-mandated norms, have a large proportion of adverse PTR schools? The answer is twofold.

First, small schools (with 60 students or less) constitute nearly half of all government schools, and are required to have at least two teachers as per RTE rules. This means that a school has two teachers even if enrolment is way less than 60. Consequently, a quarter of schools in India have less than 30 students but still have two teachers, leading to the underutilisation of teacher resources.

The second part of the problem is political interference when it comes to allocating teachers. Over the years, government schoolteachers have enjoyed the patronage of politicians as they conduct election duties in polling booths and are influential in the voter communities. Hence, teacher transfers are often dictated by teacher preferences and political pressures rather than the actual needs and requirements of the schools.

The short- and long-term remedies

Reallocating surplus teachers to schools with adverse PTR is one of the solutions to address the inequitable distribution of teachers. However, this method has its limits as it cannot be applied to states where the overall vacant teacher spots exceed the number of teachers available. In states such as West Bengal, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh, the need for teachers is far more than a mere reallocation can solve. Here’s what needs to be done:

1. Build a transparent system

Teacher rationalisation, which means the reallocation of surplus teachers through transfers, is a critical and urgent first step in ensuring adequate availability of teachers in governments schools with adverse PTR. The Ministry of Education has directed all states to expedite teacher rationalisation processes. Further, the National Education Policy 2020 has emphasised the creation of transparent online systems for teacher transfers. To this effect, many state governments are shifting to online processes for teacher transfers, setting clear criteria to allocate points to teachers, and publicly posting the decisions made regarding transfers. These steps will create greater transparency and accountability, and make the process less vulnerable to external influence.

2. Reallocate teachers

An alternative to teacher transfers is incentivising them to take up temporary positions in adverse PTR schools, until the vacancies in such schools can be filled through teacher recruitments. Relaxing the RTE Act’s rules for teacher allocation could facilitate this process. If the rule is modified such that only one teacher is allocated to schools with 20 students or less and two teachers are allocated to schools with a total enrolment of 21–60 pupils, a large number of surplus teachers will be freed up. These teachers can then be rationalised and reallocated to adverse PTR schools.

In the long run, however, school rationalisation will ensure optimal resource allocation of teachers.

These short-term solutions can help mitigate the current crisis. In the long run, however, school rationalisation, that is, the merging of two or more small schools to ensure adequate class sizes, will ensure optimal resource allocation of teachers.

3. Hire new teachers

Finally, hiring new teachers for vacant posts needs to be completed in a mission mode, especially in big states with a large number of vacancies. There have been some positive developments in this direction. In Bihar, the Patna High Court cleared the stay on the recruitment of 1.25 lakh government schoolteachers in June 2021. In Uttar Pradesh, the government has set up a panel to accelerate the deployment of teachers after hiring nearly 1.25 lakh teachers. State governments need to set specific deadlines to meet these targets. Further, the recommendation of the National Education Policy 2020 for incentivising teachers to take up rural postings should be fast-tracked. Teachers should be provided local housing and greater allowances to encourage them to take up jobs in adverse PTR schools in rural areas.

Although a necessity under all circumstances, the need to address adverse PTR, especially in rural areas, is more urgent now than ever before. Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, several children have shifted from private to government schools due to financial distress and dissatisfaction with digital education. Migration back to the villages has meant that the already struggling rural government school system is now further burdened. It is critical that our government schools are prepared to deal with greater enrolments by ensuring the availability of an adequate number of teachers.

—

Do more

- Visit the U-DISE website and find the PTR of government schools in your district and block. If the PTR exceeds the RTE mandated limits of 30 for primary and 35 for upper-primary, inform the Director of Education of the state and the District Education Officer of the district. Ask them for the reasons behind the same and demand urgent action.