In 2018, the Varkey Foundation conducted the Global Teacher Status Index survey across 35 countries to find out what position teachers hold in societies across the globe. The study measured the public’s perception of teachers’ working hours and compared these to actual hours dedicated by teachers, including the time that they spent on activities outside the classroom. In most countries, people underestimate the actual working hours of teachers; in India, teachers’ working hours are underestimated by approximately two hours per week. In addition, India was among the six countries showing the largest gap between teachers’ perception of their own status compared with that of the public.

At Apni Shala, we tried to understand what this means for our team that works in schools in Mumbai. Apni Shala aims to create education aligned with social emotional learning (SEL) by facilitating weekly sessions with both students and teachers in schools; by designing an inclusive, SEL-integrated curriculum; and through care-centred teaching practices that are informed by students’ life experiences.

During our team’s interactions with them, school teachers reported feeling that their jobs are perceived as being limited to the class or to their instructional hours. This prompted us to conduct an informal survey to understand how the common person views the role of a teacher. The respondents seemed aware of a teacher’s role in making knowledge accessible to students and in skilling them, as well as in providing moral guidance. However, there was less awareness of administrative or otherwise unseen responsibilities that teachers have, such as maintaining books or student records, checking student work, conducting parent–teacher meetings, and promoting a safe environment for learning. This shows how activities that are not directly related to student learning can be difficult to gauge.

The non-teaching labour that teachers perform is overlooked at a systemic level as well—schools, organisations, and even policymakers have failed to plan adequately for teachers’ work time. A study on teacher motivation by STiR Education and Microsoft Research India reports that one of the major challenges faced by public schoolteachers is having to carry out administrative work alongside teaching. According to teachers, administrative work takes time away from lesson planning and building deeper connections with their students.

Another report by STiR Education reveals that schools place emphasis on teachers’ administrative functions and equipping them with subject-related skills, but not on building an enabling environment for them; keeping them motivated; and fuelling their sense of autonomy, mastery, and purpose to deliver what is best for the children. Our conversations with school principals and teachers have confirmed this—it is assumed that during school hours, teachers must prioritise administrative work, whereas activities such as lesson planning and strategising classroom management are to be done outside of working hours.

Policies at any level are largely driven by data but, to our knowledge, there are few studies that explore the different sorts of non-teaching labour that teachers perform. To build on our understanding of work that teachers do and the different ways in which they spend their time to further students’ learning, we conducted semi-structured interviews with the teachers at Apni Shala. These are some of our key findings.

Emotional labour

Conversations with teachers and facilitators within our team have revealed that they spend a lot of time performing what the sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild has called emotional labour. This constitutes care-based work that teachers must engage in, but which goes beyond the physical and mental labour that is expected of the job, and therefore is often invisible and almost always underestimated.

For instance, a facilitator shared the experience of narrating a story about different types of families, after which he noticed a student withdrawing from the class. Upon speaking to the student once the class had ended, the facilitator learned that the student did not live with her family. The facilitator navigated this by making time to regularly check in with the student after class. He also consulted colleagues to gather more information to better comprehend the experience of young people living in non-traditional households. This helped him understand how to effectively respond to students’ emotional needs and support their learning in class.

Lesson planning for a diverse classroom

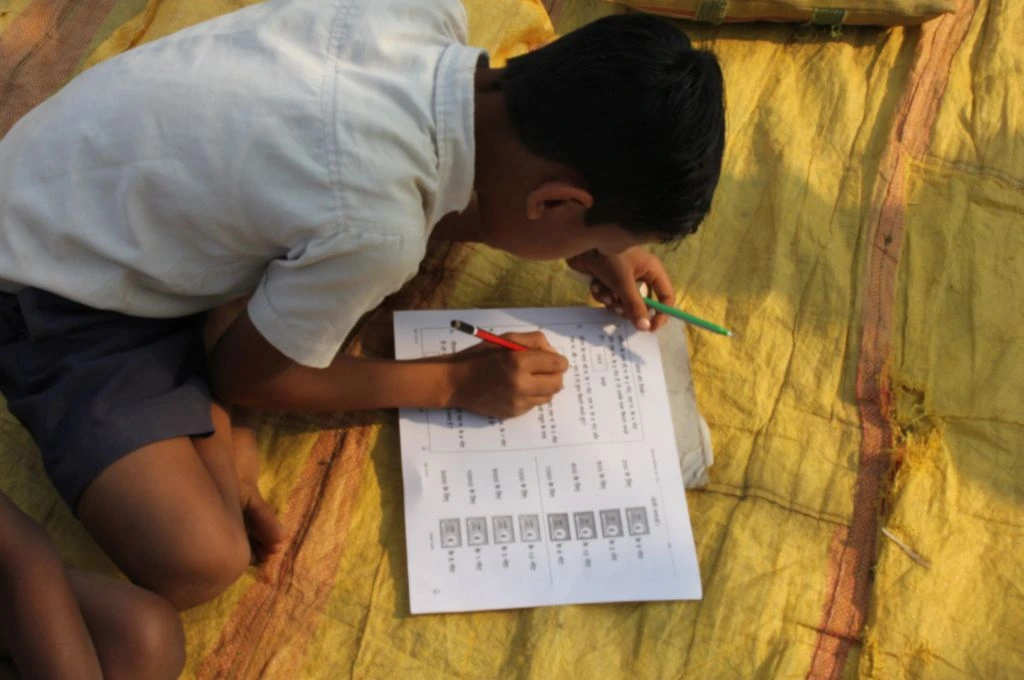

To ensure equitable learning, teachers spend a fair amount of time planning lessons, creating teaching and learning aids, and documenting and assessing learning. A grade 10 facilitator shared that in their SEL sessions, they used multiple tools (such as art, storytelling, and songs) in the same class and divided the class into sections based on students’ interests. This gives students more options to choose from and helps them remain engaged in the classroom. It also prevents the mode used from becoming a hindrance in learning and expression. But developing these tools takes time.

Another important factor in making learning more equitable is using differentiation to track progress. Sometimes this involves having to constantly assess the unique starting points of the students with respect to their skills and learnings, and then building a nuanced understanding of progress.

A grade 2 teacher at Khoj (Apni Shala’s SEL-integrated school initiative) shared that she knows the different learning needs of her students, and differentiates her approach by both product and process. An example of differentiation by product is that if the learning objective is around addition, some students learn through word problems, while others would solve numerical problems or use visual means. Differentiating by process, on the other hand, would mean that some students may work with a volunteer, while others may get more one-on-one time with the teacher.

Responding to change and decision-making

Facilitators and teachers at Apni Shala shared that to adapt to the ever-changing context of the classroom, they have to make a lot of decisions. These changes can be due to student mood, the school environment, or even students’ health concerns. Decision-making is a non-stop part of a teacher’s day as they make an array of decisions both instructionally and logistically.

In a classroom setting, decision-making means taking into account factors that range from students’ learning preferences, strengths, limitations, and needs to their varying cultural and socio-economic backgrounds. Other factors such as mood or time of the day or even the weather necessitate adaptation. (The irritation caused by a hot summer day can easily overshadow the most interesting games in a classroom.)

A teacher shared an example of a time when a student was unusually quiet and non-participative in their class. The next class was physical education, and while the rest of the students lined up to go down to the ground, this student told the teacher that they were hungry because they had not had breakfast. The teacher decided to let the rest of the students go and asked this student to stay back so that they could have something to eat before going to the physical education session.

Understanding the student

The constant information collection that teachers engage in to know and understand their students is somewhat comparable to a research project. Teachers spend time talking to other teachers who have taught their students, speaking to students after class, and engaging with caregivers/parents to get to know the students better.

During the semi-structured interviews that we conducted, teachers expressed that they were constantly engaged in building relationships with caregivers. In the context of Khoj and other schools of Mumbai, this includes calling caregivers, countless follow-ups with parents and guardians, and home visits to check in on the student and their home environment.

Interventions

The exhaustion that teachers experience can often lead to burnout. More than half the secondary schoolteachers that participated in a 2008 study reported some level of burnout, and within this group, more than 11 percent reported high levels of burnout. Research suggests that the challenges and distress faced by teachers across the globe during the pandemic added to this. In many cases, this led to teachers quitting the profession.

Here are some interventions that schools and organisations can implement to support teacher well-being, and thereby student well-being and learning.

1. Redefining work

Schools and organisations can account for the hours that go into class preparation, lesson planning, assessment grading, and more as work. Facilitators at Apni Shala’s SEL programmes reach their classes half an hour early to ground themselves and prepare for a one-hour session. This time is embedded into the programme design.

Helping educators articulate the emotional labour that goes unaccounted for can be an effective starting point towards building an environment that is conducive to managing stressors unique to the profession. As part of curriculum gatherings (professional development sessions for facilitators) at Apni Shala, participants often list down potential spaces where they might feel triggered and brainstorm strategies to manage the triggers better.

2. Implementing administrative changes

It is not a secret that rest and mental downtime can help people cope with stressors, so creating space in the structure of schools and organisations for teachers to pause can prove effective. This can be done by spacing leaves and creating a work culture where teachers feel free to actively seek rest and relaxation regularly. Setting up systems that account for relevant administrative work within work hours or distribute it equitably can also help.

A lower pupil-teacher ratio (PTR) is a change that needs to be enforced at a systemic level. The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 has called for a PTR of under 30:1 at the school level and a PTR of under 25:1 for “…areas having large numbers of socio-economically disadvantaged students”. This move recognises that the individual attention that teachers provide to students is crucial to the learning process. It also recognises that the amount of work that teachers need to put in depends on factors such as socio-economic diversity, learning differences, and neurodiversity. Implementing this is critical to student and teacher well-being, especially in densely populated public and private schools that cater to marginalised students.

3. Building a community

Fostering a community where teachers can share and address challenges, and creating spaces for teachers’ well-being and community healing, have also proven useful. At Apni Shala, supervisory structures are designed not only to promote accountability but also to act as restorative spaces that allow teachers to reflect on practice and manage triggers in classroom settings on an ongoing basis.

Team meetings and gatherings that integrate art, music, and movement or include the use of therapeutic methods or tools such as mindfulness practices have also proven useful for healing and grounding. Apart from these, friendships among teachers can create a space for care, reflection, and pause. An example is buddy systems for mental health support or checking in on one another.

While a lot can be done to support teacher well-being, systemic shifts such as lowering the teacher-pupil ratio or an intentional reduction of administrative responsibilities will play a huge role in teachers feeling supported and equipped in their roles.

—