The government recently withdrew the Personal Data Protection Bill (PDP) from Parliament. Had it been accepted as law, it would have provided an overarching advisory on the collection, storage, and use of personal data of Indian residents. Now, according to the government, the country needs a ‘comprehensive legal framework’ to regulate the online space. This would include separate laws on data privacy and the overall internet ecosystem.

Apar Gupta, executive director of the nonprofit Internet Freedom Foundation, told Indian Express that “the withdrawal of the Data Protection Bill, 2019 is concerning, for a belated regulation is being junked. It’s not about getting a perfect law, but a law at this point…It has been close to 10 years since the (Justice) A P Shah Committee report on privacy, five years since the (Justice) Puttaswamy judgment (right to privacy) and four years since the (Justice B N) Srikrishna Committee’s report—they all signal urgency for a data protection law and surveillance reforms. Each day that is lost causes more injury and harm.”

This delay is especially worrisome when we look at how digitisation has transformed the daily experience of Indian citizens over the last few decades. Today, the average number of internet connections in India has reached about 800 million. Yet, teledensity in rural areas is far lower than in cities. For instance, according to the 2019 TRAI data, rural teledensity stands at 57.59 per 100 inhabitants, in contrast to the urban teledensity, which stands at 160.63. In rural India, higher pricing for broadband connectivity and wireless access means that access is generally much lower. And with more pronounced social hierarchies around gender and caste and other social determinants, access is also restricted for segments of the population.

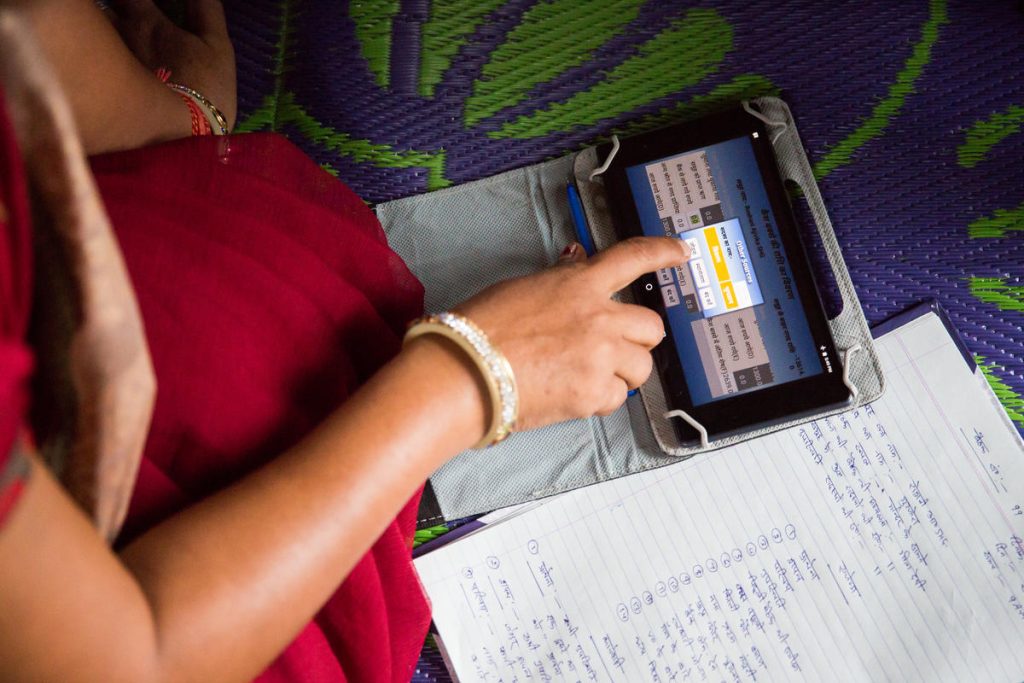

With the national lockdown during the pandemic, a lot of public services were offered via digital platforms. Schools went online too, and these shifts aided in accelerating the digital transformation of rural India. However, as with all things digital, the legal and governance response to these shifts has been playing a game of catch-up for some time now. With more and more services going digital, and more and more of our lives moving online, it is time we examine what data privacy means in our current context. We also need to consider questions of freedom of speech, censorship, and basic fundamental rights of citizens in a democracy.

Digital rights in India today

Apar defines digital rights as “the realisation of the values in the Constitution of India’s preamble— justice, equality, fraternity, and liberty—in our digital worlds today”.

Digital rights must not be considered separate from basic human rights.

According to Osama Manzar, “Digital rights must not be considered separate from basic human rights. They should not be viewed as a means to an end; instead, they are an end in and of themselves.” Osama is the founder of Digital Empowerment Foundation and is also an ‘Ashoka Special Relationship’, having been elected to their fellowship through a virtual process.

This line of thinking becomes especially relevant when we consider the growing emphasis on providing services, facilities, and opportunities via digital means. In a country where universal digital literacy and access are still a ways away, making access to public services contingent on digital infrastructure means that we are in fact leaving a large section of our population behind. And, in doing so, we are deepening the same historical inequalities that have existed in our society for centuries.

Where does this place the democratic promise of digital?

Apar believes that the central government has invested significant resources when it comes to internet access, especially in the creation of network infrastructure and its availability across states. Hubs have been created in villages for internet access. The government has also allocated funds towards the creation of the National Broadband Mission. “However, access hasn’t been unlocked at the pace at which technology is being integrated into people’s lives,” he says.

Additionally, not enough people have devices to take advantage of connectivity, wherever it does exist. So adoption of services isn’t quite where it could be. And, lastly, access isn’t equitable. For instance, being predominantly English, most of the internet is quite exclusionary in a country like India.

Given these challenges, Apar thinks that “it will take time for the government’s initiatives of connectivity and access to match up with the larger aspirations we have around governance of the digital space. This means that policymaking must reflect the ground realities of India today, and we can’t leave people behind. Here, it is also important to ensure that digitisation is grounded in democratic values, and it provides power to the users where their freedom of speech and privacy is protected.”

This is where civil society should come in

Nonprofit organisations at the grassroots are well placed to support communities with issues of digital literacy and access, given their close relationship with people at the last mile and understanding of community networks. However, few organisations are actively engaging with digital rights today.

Osama believes that the sector—nonprofits and funders alike—has “failed to understand the integral value of digital in every aspect of life today”. “We need to figure out how to make civil society understand that digital rights are no different from any other development issue. In fact, if digital is integrated into programming, everything will be much faster and better in the long run because, in any case, there is no future without digital. It’s just a matter of when and how to make it contextually relevant. We need models that are a hybrid of online and offline so they can respond to the needs of the community. And we need funders to also think about integrating digital into the programmes they fund.”

There are a handful of organisations working actively on digital rights.

The role of nonprofits can also extend beyond their own programmes to overseeing policy implementation at the grassroots. Nonprofits can make sure that schemes reach the people who need them the most. The challenge in fulfilling this role at scale, however, is that the number of actors in this field is limited—there are a handful of organisations working actively on digital rights. Their proliferation hasn’t matched the rapid transformation that is taking place in our society through digital technologies. Moreover, conversations and considerations around data privacy—a growing concern with platforms like Aadhaar and CoWIN—are few and far between.

Organisations should examine their operational practices, questioning whether they really need all the data they collect. At times data collection may also be a function of what funders require, which is why data minimisation—gathering the least amount of data possible to fulfil one’s purpose—is useful for funders as well as government actors.

Data is not without errors and is prone to manipulation

According to Osama, “One of the most important considerations when it comes to data and privacy is not just when you take the data, but also what you do with that data beyond the purpose for which it was collected.” Data can have very real repercussions on people’s lives and safety—for instance, if the data collected becomes available publicly and reveals an individual’s caste.

Moreover, when everything is online, glitches and errors can deprive people of basic fundamental entitlements such as rations and pensions, and, as we saw with the CoWIN app, the right to mobility and employment.

In June this year, a two-year-old digital database built to consolidate land records and make life easier for millions of farmers in Telangana ended up erasing hundreds of them from its records. Farmers woke up and logged into the Dharani platform only to find that they no longer owned their land. In fact, this kind of land acquisition from farmers has happened before. An Article 14 piece quotes Kanamoni Ganesh, a farmer from Medipalle village, stating that digital ‘glitches’ like this one where their names were erased, is just the government’s latest strategy.

What we need in India

We need to approach data privacy laws in India in the same way that we did the Right to Information Act. It was a grassroots movement that was built from the bottom up. Today, our thinking, language, and approach for digital rights, data privacy and freedom of expression is top-down, and because of this our laws will end up excluding more citizens in the long run.

In pushing digital indiscriminately, we are failing to understand how societies work, how communities work.

According to Osama, “In pushing digital indiscriminately, we are failing to understand how societies work, how communities work, and how we facilitate them with their rights, given the new means of serving them.” We therefore need to place greater emphasis on intersectionality; in today’s world, we cannot address issues of sanitation, gender, health, and rights without providing equitable access to technology with adequate safeguards for people’s data.

Ultimately, the larger challenge in the years to come will be to make digital literacy materials around digital rights much more inclusive and participative for all Indians.

—

Know more

- Learn about data privacy laws around the world here.

- Listen to this podcast to understand why the government needs to make access to technology more equitable.

- Read this article to learn more about the digital divide in India