India is urbanising rapidly. According to the World Bank, approximately 35 percent of the country’s population lives in urban areas. This figure is expected to increase—projections by the UN indicate that by 2050 more than 50 percent of India’s population will be urban. However, contemporary Indian cities are plagued by problems such as inadequate housing, unequal access to sanitation and water services, and poor public health. If we expect our cities to adequately serve their residents, they need much better infrastructure. The pandemic has made this abundantly clear.

But when we talk about better infrastructure and better facilities, what do we mean? Who takes the decisions about what infrastructure gets prioritised, and how are these decisions taken? And, finally, what sort of infrastructure do India’s cities really need?

On our podcast On the Contrary by IDR, host Arun Maira spoke with Sheela Patel and Ireena Vittal on what it takes to plan and run a well-functioning city, where Indian cities stand, and what they need. Sheela is the director of SPARC, an Indian nonprofit that works with the urban poor so they can get access to housing and other amenities. Sheela has experience both at the grassroots level as well as at the level of national and global policy. Ireena is one of India’s most respected independent consultants and advisers on emerging markets, agriculture, and urban development.

Below is an edited transcript that provides an overview of the guests’ perspectives on the show.

What makes a city liveable?

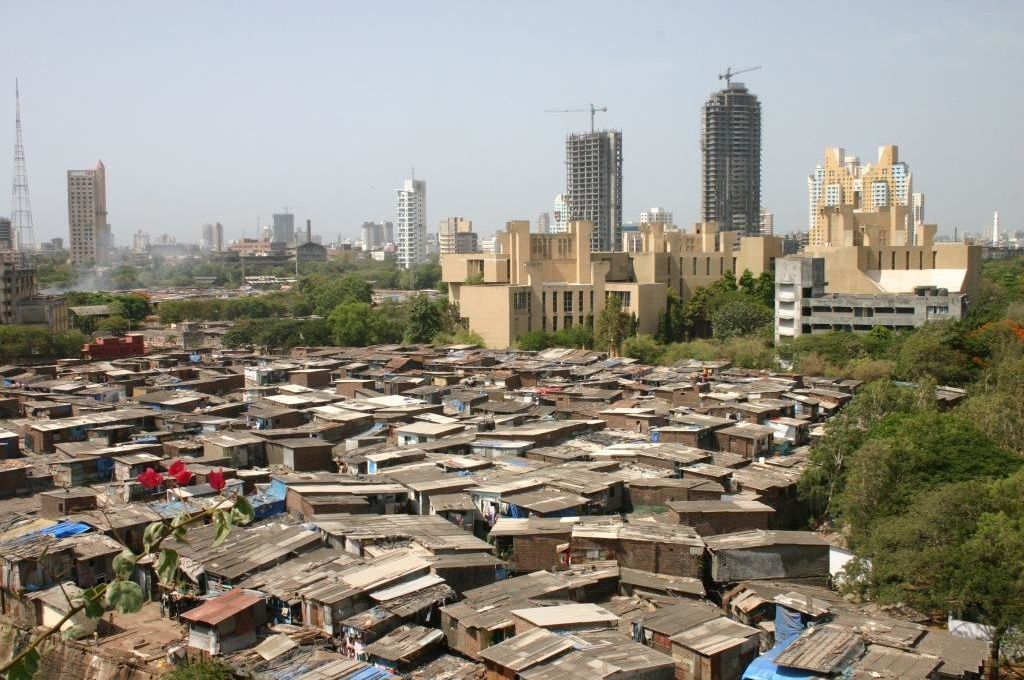

Ireena: I think I would put the following six [factors]. The first is jobs. A city is investment meeting talent to create economic and social outcomes. So, jobs, [that is,] number of jobs, quality of jobs [is an important indicator]. [The] second is inclusion. [For instance], a city [should] have place for both sides of Gurgaon divided by the highway, for Dharavi and South Bombay. And we need inclusion not as a cool thing to talk about in nonprofit conferences, but as a recognition that the most valuable contribution to society comes from some of our most ill-paid people, whether they are sweepers, or cleaners, or biomedical waste collectors, or peons, or delivery boys.

[The] third is safety and amity. If you’re a person in India—woman or man—you value safety. Amity [is important] because, unfortunately, the whole world seems to be going through some kind of a manthan (agitation). The fourth one would be provision of basic services, whether it’s water, schools, ICU rooms, maybe now even oxygen, sanitation.

I would add two more. One of them is resilience and green…You see what’s happening even in Bombay—the number of days Bombay comes to a stop now every year because of climate change is astonishing. So we need resilience and green. And finally, culture. [It is good] if we are able to feed our stomachs, but there’s something beyond that. And culture is not Bolshoi Ballet; culture is street plays and music and Ganesh Chaturthi. And if a city doesn’t have culture, it doesn’t have soul. So, to me, these would be the six metrics that I would put for liveability in the Indian context.

Sheela: For me, the real transformation in cities that we are looking for is that, while it is a utopia to think everybody will be equal all the time everywhere, increasingly, human rights, social justice [activists are] saying that at least there should be a minimum safety net for all. And the COVID-19 crisis has shown [that this] does not exist at all, both locally [and] globally, urban and rural. But in urban areas, it is very visible. If cities are safe for women and children, if cities serve the health, education, safety, and potential nurturance for young people, then it’s a good city.

What does it take to plan and run a liveable city?

Ireena: I think the process of making a city happen starts with two or three fundamental constructs. One is that citizens don’t know what they want. I spent a day once with the original city planner of Singapore, and he was talking about the early days of how they reimagined Singapore, and he has such a fascinating story. When they were building their public housing, they had a very interesting set of planners. They [involved] urban planners, engineers, historians, sociologists, psychologists, religious people, so they represented all facets of your life and my life. But they had two choices in the way they were designing those big homes that you see in Singapore. You could [either] have all the doors opening onto the corridor or you could have them step up and step down, so it created a sense of privacy. And one of the things that they did was they would test everything…and you know how Singapore tests—it puts it out in retail spaces, and citizens come and then literally write their comments. And he said [that] every time they tested design choices or any infrastructure prioritisation choices, [they] would get 50–50, because people don’t know. So a voice is different from a vote. It’s about aligning people; it’s not necessarily about outsourcing the decision to somebody.

The second piece, in the process of running a city, is to prioritise. And I think at the heart of prioritisation is two things: the economic plan for the city (what kind of talent, jobs [exist]? What kind of quality of life do you want to deliver?) versus the spatial plan for the city (is this a series of cities where nobody will travel more than 10 minutes from home to work? Or is it a longitudinal city? Or is it a vertical city?). Those are very, very different choices.

And then the last piece is resourcing—resourcing in terms of funds, but also in terms of capacity, both to build [and] to deliver.

Indian cities: What’s missing, and what we can do better

1. Looking at the well-being of all citizens

Sheela: The urban geography is now the dominant geography, and investments that we make in cities have to anticipate not only past deficits but also future challenges. Just take the instance of infrastructure…if you know what poor people need…they need security for the place they live in. They need water sanitation, electricity, [and] transport. And they need good-quality food, and good-quality health systems, they’re all connected. Now you have cities, not only in India, but globally, [that] are not able to make the kind of investments that they need…The economic order of our global economy has pushed more and more people into cities to earn cash incomes, [and] we don’t feel responsible to ensure that they have a minimum wage…And if you look at what happened during the COVID-19 crisis, everybody realised how many migrants there are in our country when [they] saw the images of all those people who were walking back because they had lost their incomes—they didn’t even have money to recharge their phones to tell their family. They couldn’t live in the informal settlements where they rented a bed, which is all they could afford…And we are [still] not acknowledging how much the poor are contributing to [everyone’s] survival.

I believe that the proper benchmarking of what is missing, creating clarity of what communities, whether elite or poor, need to do themselves; what the city needs to do; and what the educational system needs to do today, in colleges of engineering and architecture, and planning…But minimum safety nets [for all] is critical.

Ireena: We were doing some work as part of a nonprofit in Bangalore once, at ward-level budget planning…The interesting part of the story was that we were meeting in Jayanagar once, which is a tony neighbourhood of Bangalore. Somebody decided that it had to be a representative bunch of citizens, and so we invited people [from] all sections of society into somebody’s home. What was astonishing was to see how people behaved and, more importantly, what was on top of their mind. The people who came from the slums, or who were from a lower class, sat on the ground, and the person who was leading the effort and came from a different class sat on top of the sofa. While the people sitting on the sofa, and I’m using it, not in a pejorative way, talked about green, cycling paths and better roads, the people sitting on the ground talked about electricity. They talked about safety in the night, they talked about drainage. And so, to me, what you see depends on where you stand. And I think one piece that’s missing in our whole discourse is understanding multiple constructs that live simultaneously and adjacent to each other. If you want to be successful, I think we just need to bring that mindset that we need to serve many Indians, and they all are legitimate. One is not better than the others.

2. Focusing on the execution and delivery, in addition to the planning

Ireena: I think the other point is, think of the construct of a city…You have to think through what a city needs from a long-term point of view and prioritise—should I build a road, an airport, or a power plant—because you have only this much money. You have to then design [and] resource it. Because none of our cities, maybe with the exception of Bombay, are self-sufficient. Even Bombay is not, given the amount of investment… and resourcing means property tax, collecting for water, collecting for power, raising debt, getting a rating, maintaining books of accounts, which most of our cities don’t know how to do. You’ve got to resource it, you’ve got to build it, you have to deliver it. And then you have to manage it—the politics of it, and the society of it…prioritising, designing, resourcing, building, delivering, aligning, and managing politics and social equity. [And] a lot of our conversations are about what needs to happen. We don’t have enough conversations on who will do it, and how [they] will get it done. And that is the piece, the invisible but critical infrastructure that I think our cities need.

3. Ensuring continuous dialogue between different stakeholders

Sheela: There is a need for a huge transformation in all our collective thinking. And for all of us, whether you’re in finance, you’re in business, or we, as activists, we need to reconcile to the reality that we are sharing space in the city, in this planet; we have to start talking to each other. [For instance,] I have learned to talk to business and to municipalities, not because I think that is so smart and strategic. I was forced by [the] community, by the women who are facing evictions…[They told me], ‘If they demolish our homes, you go and talk to the municipality, you go and talk to whoever it is…to the collector, to the government…and find and negotiate for an alternative where we can coexist.’ So there’s a lot of appetite for negotiations [and] dialogue. [What] we need [is] leadership, to have the guts and the courage, both in private [and] public life to listen to what others are saying…You don’t have to do magical things, you just have to make sure that those dialogues happen long before the destruction happens.

4. Enabling citizens to be actively involved in the planning and operation

Sheela: People also have to change. You can’t change other people and not change yourself. The collective nature by which we deal with crisis came up very strongly during COVID-19, in terms of support, in terms of assistance, but it’s always only in that emergency…If communities are able to identify what they need, and they make that representation, together go to the municipality, and the municipality [then] empowers its local ward officials to take this forward, the local machinery begins to work. When the local machinery begins to work, it allows those who are above that to look at the next level. Can you imagine the crisis of a commissioner who gets a phone call saying ‘my drain is clogged’ or ‘I can’t get vaccination’? If he or she looks at that, then when are they going to look at the city-level problems. So we’ve got to create a hierarchy of problems that have to be solved at each level, and they have to be monitored. What we are doing is we’re not only identifying issues, but [the] community [also] monitors them with the local officials and elected representatives, so you have a hierarchy of decision-making.

Cities have skill sets, capacities, systems—we just need to empower them to start with, then the more detailed challenges will come up.

[However], while the local is very critical, there are also things of scientific disruptions and breakthroughs that are necessary at different levels. So I don’t want to reduce their importance and value. The important thing is that it becomes a circle, that with those breakthroughs, for instance, with solar [energy] you can leapfrog the whole energy shortage. When I went to Berlin, and I heard that there were electricity and solar transfers in every household, I thought, ‘When will it come to India?’ But it’s come to India, and we could easily have it cover all the informal settlements, and that would make 30 percent of Mumbai’s energy coming from alternatives. [However, this] decision communities can’t take; [it] has to be taken at the national and at the state level.

You can listen to the full episode here.

—

Know more

- Learn more about the major issues plaguing Indian cities and how urban planning can be reformed.

- Read this report to learn more about the concept of liveability and how it can be introduced to Indian policy frameworks.

- Read this report on the constraints to raising private financing for urban infrastructure in India.