Across the world, cities have been designed for men, by men—especially young, healthy, cisgender men. This leads to many challenges—for women, for the young and elderly, transgender community, and anyone else who does not fit into this fairly homogenous group of young, able-bodied men. Around the world, as cities begin to realise these limitations, a small but growing number of them have begun to experiment with doing things differently—sometimes with surprising results.

For instance, a study in Vienna in the mid-1990s found that boys tended to take over public play areas like basketball courts, crowding out the girls. By dividing large parks into multiple spaces, and creating more female-friendly spaces with benches that appealed to girls who wanted to hang out with their friends, and creating alternative play areas such as badminton and volleyball courts for the girls, they were able to create public spaces where girls could feel as comfortable as boys. Vienna introduced gender-budgeting since 2006—a study indicates that the city carried out more than 60 initiatives using gender mainstreaming, including street-lighting projects, introducing apartment complexes and social housing designed by and for women, and improving the safety of shortcuts and alleyways by installing mirrors.

An architectural firm in Sweden, which engaged with girls to understand why they did not use their play areas as much as boys, found that they wanted “spaces close to other people but not at the centre of a crowd from where they could see but not necessarily to be seen.”

Sadly, the firm realised that they could not think of a single project where a city space had been designed specifically for young girls to use, in consultation with them. Indeed, women typically constitute only 10% of the senior positions in architecture and urban planning worldwide, a grim statistic that tells us why cities are so ill-designed for women.

The bias runs even deeper.

Public datasets that inform planners, such as open source Google Maps, depict cities through a male-centred gaze—most of the entries come from men. Thus, services important for women—such as hospitals, childcare centres, and domestic violence shelters—are often missing.

Women’s activist groups can play a major role here. GeoChicas, a group created in Mexico in 2016, which has now spread to 22 countries across Latin America and Europe, organises mapping events so that women who face gender-based violence in Latin America can get safe, reliable information on where to go for help. Safetipin, an organisation that began in Delhi, uses crowdsourced data from women to develop maps of unsafe areas in cities like Delhi and Bhopal, working with government and non-governmental partners to create safe public spaces for women to access, even at night.

Such feminist approaches, which seek to co-create action for safe cities with women, are starkly different from the typical Indian city administration response to incidents of violence against women, which tend to focus on ‘smart tech’ initiatives like CCTV cameras—ideas that may make women even less willing to come out onto the streets . Instead, simple changes like better street-lighting, and mixed land use, which allow more street vendors to operate, and are preferred by women, are rarely implemented.

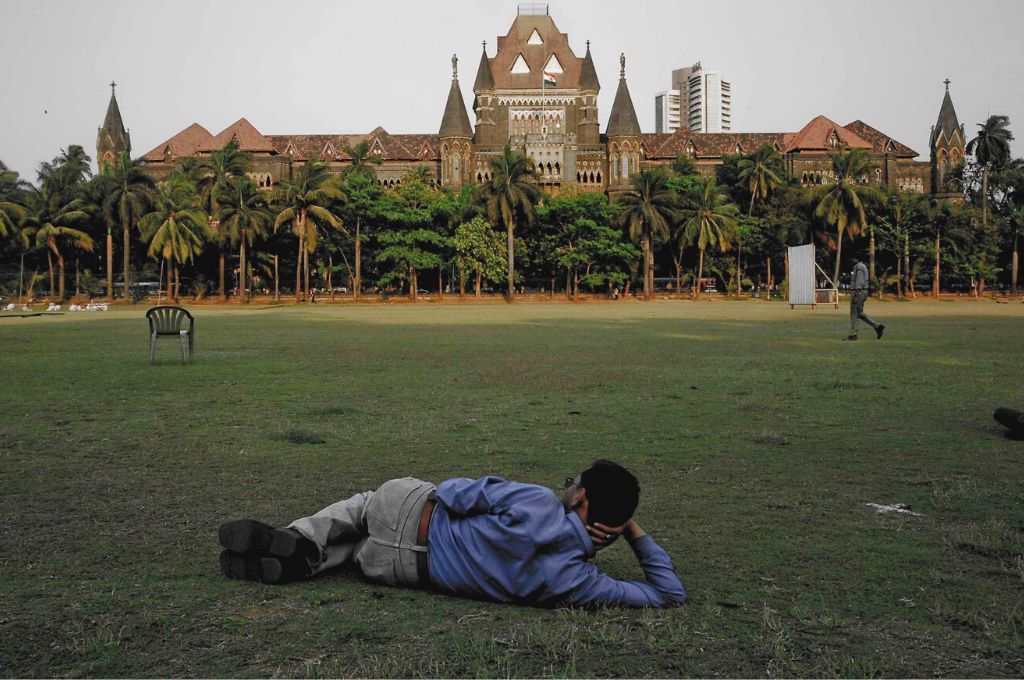

Our research in multiple cities across India focuses on spaces of nature, and how they are accessed by different groups of people—men vs women, privileged vs oppressed caste groups, wealthy vs poor, etc.

In Delhi, while conducting surveys of park visitors, we found that women rarely tend to visit parks alone or even in smaller groups.

Safety, security and better facilities for children to play were issues that women sought, far more than men.

Men visited parks closer to their homes frequently, and often alone: for many of the women we interviewed, a visit to the park was a rare outing, done perhaps once or twice a year, in the company of large family gatherings. Safety, security and better facilities for children to play were issues that women sought, far more than men.

In Hyderabad, we found similar issues shaped womens’ access to parks. In general, women preferred to visit smaller parks, where all parts of the park are visible, feeling more secure there.

In large parks, where some areas were isolated, visits by tourists were high, but such parks were less visited by local women residents because of safety concerns. Women also repeatedly said that they had less time, compared to men, to visit a park every day and take out some time for themselves in the midst of endless domestic duties.

Many of them come with their families. As one woman said, “The place I live in has no parks anywhere near, so we come here at least once in six months to have a family outing and picnic. I think these parks should be everywhere.” Another woman said, “I bring my mother here on [my] free evenings. It reminds me how my mother used to take me to parks back in my childhood.”

Yet women also describe how important it is for them to have a social network of people to meet in the park. Domestic life can be rather isolating, especially in cities.

One woman narrated a story of how she escaped from domestic abuse by relying on friends she had met in a park near her home, who helped her reach a place of safety. Others spoke of how their visits to parks made them feel less lonely, less depressed, and less isolated in the city.

This seems especially true for immigrants to a new city, who struggle to make new friends. One woman said, “I am from Kerala. Hyderabad is not green enough for me. I have grown up in forests—I don’t find much connection here. But this park was a major reason for me to buy an apartment next to it. It helps me to survive Hyderabad.” Another had this to say, “My son brings me here whenever I feel like going out somewhere. I love trees and flowers. My son and everyone else are busy in the family. At times they drop me here on their way to the office. I enjoy being here, and rarely get bored even when alone.”

Class, caste, socio-cultural and economic backgrounds shape how women use public spaces too.

Class, caste, socio-cultural and economic backgrounds shape how women use public spaces too—especially spaces of nature. In Indian cities, which are extremely unequal places, even if we crowdsource data for better public design keeping women in mind, we may end up collecting data from women who speak English, who can use apps, who experience the city in one specific kind of way. This can result in other forms of exclusion. For instance, in Hyderabad, women from high-income families supported the idea of parks with ticket prices, as these fees provided money for the park authorities to provide better security, improved facilities and improved maintenance.

But other women said that once parks started charging for entry, they stopped bringing their children daily. When parks became ‘better maintained’, guards stopped them from collecting grass for their cattle, flowers for worship, and dried twigs as fuel for cooking.

They had to rely on informal ‘arrangements’ with friendly guards, or resort to bribes, to collect material from the parks—something that they had done for years before the park became a formally managed, ‘improved’ urban space. One woman said candidly, “We brought our children to the park as their first outing three years back; now the place is very different. It was lot more free and nicer back then. Now the new rules have changed the flavour of the park.”

In Bengaluru, a lake that used to be part of a local village a few years back, has now been gentrified and transformed into a managed urban space with jogging and walking paths. A long-time resident of the village described her former life at the lake. “We used to work and sing songs, we found happiness in it. We kept walking around the lake. It was believed that the Amma takes bath at the lake at 12 in the night, along with many other goddesses—we felt some kind of vibration there. They used to send the women away from the lake after 6 pm. In my village, women used to do kolata (a folk dance with sticks). It would give happiness to us, ease the burden of work and bring us joy. Everyone would give a little bit of their farm produce and collectively do puja and distribute it to everyone in the village.”

Another woman said wistfully, “When the lake filled up, we used to light diyas, sacrifice a lamb, and cook there. We would eat on the banks of the lake and celebrate. We would do the same if we got a good harvest. Whoever had their own land, would use the lake water for irrigation. We used to eat the greens that grew around the lake as well. It was really beautiful in the past. If my husband came home early from work, both of us would go to the lake together. It was beautiful to see. I have only not seen the lake in the past five years.”

Restored lakes are beautiful green spots in the heart of a crowded urban city. But if they keep out the women who used to use these lakes in the past, then such restoration is incomplete. However, the growth of the city has dissolved some of the restrictions that caste hierarchies placed on women from underprivileged castes.

Women from these castes were not allowed to wash their clothes in the lake, but forced to rely on the wastewater instead. They were not permitted to take their cows to the lake bund; today, no one can restrict their access to any part of the lake. Their agricultural lands, wells, even their goddesses have disappeared from the lake periphery, replaced by concrete, high-rise apartments and roads, accompanied by the stench of sewage and the blaring cacophony of traffic.

The physical, tangible erosion of caste ostracisms with regard to the restored lake is progress on one front, while the loss of their shared social-ecological life around it is a step back.

Restored lakes also have migrant workers, who hail from similar socio-economic backgrounds as many women from these erstwhile village communities, who also live around the lake. The former perform similar jobs, either as domestic workers, or construction labour, and earn similar amounts of money. But migrant workers are especially disenfranchised. They live in temporary shacks, without family support, and are moved from place to place by their contractor.

When one of our colleagues asked a woman who lived in a blue plastic tent on private land right next to a restored lake if she ever went to the lake, she burst out laughing, asking if we thought she had the time to go jogging at the lake.

Her children and husband sometimes went to the lake, she said. But where did she have the time to go? When they returned in the late evening after a long day of work, her chores at home began. She had to wash clothes, clean the utensils, and cook dinner for her family. There was no time for leisure.

Children in government schools, which often lack the space and money for playgrounds, cannot access these spaces.

Several of these lakes and parks have schools—often government schools or aided schools, which cater to children from low-income homes—at their boundary. The exclusionary nature of public planning cuts deepest here. Parks are closed from 10 am to 4 pm on weekdays in many Indian cities. Thus children in government schools, which often lack the space and money for playgrounds, cannot access these spaces. Boys may find ways to make up for this after school hours, running free along the roads, and in and out of each other’s homes. But the freedom of girls is much more restricted. They go straight home after school, and stay there for the most part. Closing public parks means depriving them of freedom. Even worse—when parks and lakes are closed during school hours, this means that girls—often menstruating—are denied access to public toilets, and have to hold themselves all day. Forget access to play spaces—when we deny young girls access to basic sanitary facilities, the city shows us its cruellest side.

How does one plan public spaces for all women? Young girls at the cusp of adolescence seek non-judgmental, freeing spaces to be themselves—but are excluded from such spaces by gates, guards and timings. Women from erstwhile village communities have a strong, deep-rooted and sacred connection to lakes, but cannot recognise these water bodies in their new avatar, transformed as they are into landscaped recreational sites with long lists of prescriptive rules. Women from migrant worker families have no time for leisure despite a deep need for it—can there be some way to give them a break in public spaces? And what about the women that the public planner is perhaps most familiar with—from a middle-class or wealthy home, who seeks a place for some solitude and time with families to wind down after a busy day? Even she, who is the most privileged in this set, finds herself deeply disadvantaged in comparison to men. Urban nature, a woman whom we interviewed recently mentioned, was also much valued during the COVID. “So then when we meet up at the lake, we get the opportunity to meet different kinds of people with whom you can develop different kinds of interest. Somebody’s into singing, somebody’s into cooking, somebody’s into sewing. A kind of informality connects us there which carries away the daily distress in your minds—especially in these extraordinary times. And I think it’s very important to have that kind of informal chats and discussions because we look forward to that, considering so many other complexities.”

The world has a long way to go in planning its cities, its public spaces, to be women friendly. But India perhaps has the longest journey to make. We need to find more ways to bring women’s voices out strong and loud, in collectives—without privileging one type of woman over another. Otherwise, we will continue to leave half the population out of consideration.

This article was originally published by The Third Eye.