The Loss and Damage (L&D) Fund was conceived by member parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). It serves as a financial mechanism to address the unavoidable and irreversible impacts of the climate emergency. The fund encourages voluntary contributions from developed countries, but invites developing countries to contribute to it too.

Despite countries adopting an array of policies to mitigate and adapt to climate change—such as investing in clean energy and energy-efficient technologies and installing early warning systems—it is evident that these efforts alone will not suffice to prevent all climate-related disasters. Even if global warming is miraculously limited to the 1.5°C threshold, the intensity, frequency, and unpredictability of extreme weather phenomena will continue to cause unavoidable and irreversible loss and damage for years to come. This holds true for both rapid-onset events (such as cyclones, floods, and landslides) and slow-onset developments (such as desertification, ocean acidification, biodiversity loss, and rising temperatures and sea levels).

As for developing economies, strained resources are further taxed by the additional costs of climate damage. They bear the brunt of climate change more heavily than developed nations. According to the sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the average mortality from floods, storms, and droughts in particularly vulnerable countries is 15 times higher compared to countries with very low vulnerability. In India, the potential income loss from the reduction of labour capacity due to extreme heat was estimated to be USD 159 billion, or 5.4 percent of the country’s GDP, in 2021. The L&D fund has primarily been established to support vulnerable countries with the resources they need to recover from climate impacts both economic and non-economic. Loss of livelihood, crops, property, and ultimately the national GDP count as economic losses because they can be assigned a monetary value. On the other hand, injury to and loss of life, health, rights, biodiversity, ecosystem services, indigenous knowledge, and cultural heritage are categorised as non-economic losses. Loss of income from working days forfeited to heatwaves is an example of an economic loss, while the displacement of communities from coastal villages due to beach erosion would count as a non-economic loss.

Is it the same as adaptation finance?

The L&D fund has emerged as the third pillar of climate finance alongside adaptation finance and mitigation finance; it is meant to help communities restore and rebuild what is lost and damaged. The fund can be utilised, for example, to rebuild infrastructure destroyed by extreme weather events, establish resettlement colonies, set up alternative livelihood programmes, offer counselling services, and initiate projects to commemorate the loss of life and cultural heritage. Some reparative actions—for example, a resettlement housing colony for people displaced by rising sea levels—could be categorised either as adaptation or as loss and damage. However, the commonly understood threshold separating one from the other is that loss and damage includes impacts that are beyond the limits of adaptation. Put simply, it’s when loss and damage occurs even after adaptation measures have been deployed, either because the measures are ineffective or due to the unanticipated severity of the climate impact. The more effective and timelier the adaptation strategies, the lower the risk of loss and damage.

How did the fund originate?

The L&D fund was operationalised at the 28th Conference of the Parties (COP 28) held in Dubai in November 2023. However, it has been more than thirty years in the making. The proposal for climate-related financial assistance was mooted as early as 1991, when the UNFCCC was being drafted. At the time, Vanuatu, the Pacific Island nation representing the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), rallied for a globally contributed insurance scheme to assist countries impacted by rising sea levels. The proposal was ignored.

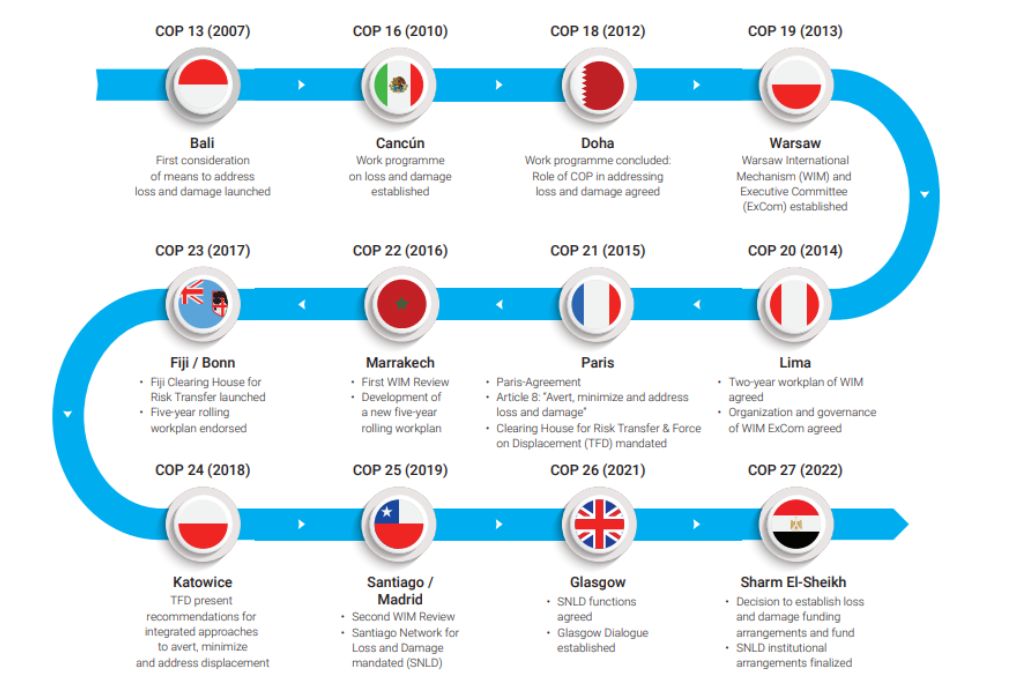

It was in 2007, at the COP 13 in Bali, that the term ‘loss and damage’ first appeared in a UNFCCC decision. Inked into the Bali Action Plan, it outlined three thematic areas of work: assessing the risk of loss and damage, exploring a range of approaches to address it, and defining the Convention’s role in implementing the approaches. In 2013, the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage was formed to enhance knowledge of risk management approaches to address loss and damage, strengthen dialogue and coordination between stakeholders, and mobilise financial, technological, and capacity-building support for it.

However, the crucial ground plan for funding remained sketchy. The economics of reparative action was once again left out of the 2015 Paris Agreement, in which loss and damage was covered in Article 8. It spelled out the importance of averting, minimising, and addressing loss and damage, and formulated potential scenarios of loss and damage that nations, particularly vulnerable ones, were likely to encounter in the future.

It was finally in 2022, at COP 27 in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, that money was (notionally) placed on the table, when Parties agreed to operationalise a dedicated fund to address loss and damage. A transitional committee—comprising representatives of 24 developing and developed countries—was appointed to discuss its governance and institutional framework, funding arrangements, and implementation. Over the course of a year, the committee held five meetings, two workshops, two ministerial meetings, and a dialogue. After protracted negotiations, it submitted its report to the Conference of the Parties. And thus, the Loss and Damage Fund was operationalised on November 30, 2023, at COP 28 in Dubai. This also marked a first in the history of the summit: the adoption of a monumental decision on day one. An independent secretariat and governing board were appointed. The World Bank was appointed interim trustee and tasked with hosting the fund for four years. It would oversee the coordination, collection, and allocation of resources in consultation with the Warsaw Mechanism, the International Monetary Fund, and the Santiago Network.

Why are critics sceptical?

More talk, less action:

Since November 2023, the L&D fund has received USD 661.39 million in pledges from several countries, with others expected to contribute later: Italy and France pledged USD 108 million each, Germany and the UAE USD 100 million each, the UK USD 50.6 million, Japan USD 10 million, while the US—the world’s largest economy and second-largest carbon emitter after China—pledged only USD 17.5 million. Experts say the money that all of these countries have pledged in sum is inadequate and covers less than 0.2 percent of what developing countries need, which is a minimum of $400 billion a year as per The Loss and Damage Finance Landscape report. Developing country members of the Transitional Committee proposed that the fund programme a minimum of USD 100 billion a year by 2030.

The gulf between what developing countries need and what they receive has not only severely compromised their ability to adapt to climate change, but has also heightened the risk of greater loss and damage in the future—risks already amplified by the delay in mobilising accessible climate finance. A report by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) estimates that India itself may require USD 1 trillion between 2015 and 2030 for adaptive actions. The Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) pegs the country’s investment needs for adaptation-based development at USD 14–67 billion annually, for the same 15-year period.

Concerns around climate justice:

Climate justice is anchored in a principle of international law called ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ (CBDR), which acknowledges that even as all countries are called to take mitigative steps to reduce climate impacts, some have a higher responsibility—and capability—to address climate challenges than others.

By this measure, developed nations, which have had a long head start in building and benefiting from their fossil fuel-based economies and are the primary drivers of climate change—ought to pay a proportionate price towards climate finance, one that helps developing countries deal with it effectively. Who pays, and how much they ought to pay, are vital questions that need to be addressed. The Adaptation Gap Report 2023 emphasises that “a justice lens underscores that loss and damage is not the product of climate hazards alone but is influenced by differential vulnerabilities to climate change, which are often driven by a range of socio-political processes, including racism and histories of colonialism and exploitation.” Critics point out that the fund falls short on delivering on climate justice by failing to set clear, fair, and time-bound expectations on payment, and by doing so, undermines the principles of equity, historic responsibility, and polluter pays, which are codified into the Paris Agreement.

Lack of clarity on operationalisation:

The hard-won voluntarism written into the body text of the COP 28 decision text absolves developed countries of all liability. By inviting them to contribute instead of requiring them to compensate for their relative contributions to global warming, the treaty shields them from potential litigation claims by developing countries. Moreover, there is no floor set for the quantum of the fund. Had developed countries been held to account, they would have had to pay far more than they pledged. By one calculation, the US’s fair share of loss and damage finance in 2022 alone was USD 20 billion, rising to USD 117 billion annually by 2030. The lack of legally binding commitments also has advocacy groups concerned about the long-term stability of the fund. Timing is another concern. With developed countries having delayed nominating members to the Loss and Damage Board, one worry is that efforts to operationalise the fund in time will be hampered.

One way to address the technical shortcomings of the mechanism is to include it in the global stocktake (GST), the five-yearly review initiated to monitor progress on the Paris Agreement’s long-term goals. The GST, however, does not address loss and damage as a separate pillar, as it does adaptation and mitigation. This, experts say, may result in L&D being subsumed into the adaptation assessment.

Articulating what constitutes loss and damage can advance research on the subject.

Critics have also drawn attention to the need for a clear definition of loss and damage and of what constitutes non-economic losses and damages, which the UNFCCC is yet to frame. The lack of distinct parameters increases ambiguity around which kind of impacts and which countries should be prioritised for the money. Interpretations of the term range from the effects of anthropogenic climate change to only those that occur after the adaptation ceiling has been breached. Articulating what constitutes loss and damage can advance research on the subject and help formulate concrete actions to address it. But actions are reliant on data and there is scant data on these twin themes (loss in particular), not least because of the lack of clearly defined processes and tools to record, measure, and report them.

It’s therefore vital to establish standardised assessment methodologies at the national, subnational, and local levels of what constitutes loss and damage.

Sources of finance:

The fund is expected to be built with contributions from a spectrum of sources, including public and private finance, and innovative funding instruments such as taxes, levies, and debt swaps—primarily from developed countries. However, the process for capitalisation (beyond initial commitments), has not been spelled out.

In addition to public finance such as government-issued sovereign green bonds, alternative inflows to the fund could come from multilateral development banks, climate funds, philanthropies, carbon markets, and from carbon taxes and levies imposed on historic, large-scale polluters like the fossil fuel industry and the aviation and maritime sectors. Some states in the US are in the process of legislating for a ‘climate superfund’, which would make fossil fuel producers and refiners liable to pay for local adaptation measures and loss and damage expenses.

Private finance, in the meanwhile, can be raised through bonds and loans, although these run the risk of being conditional and extractive, privileging institutional profit over public interest. The Loss and Damage Finance Landscape report warns that “funding mobilised through financial instruments which seek to profit from the climate crisis, create greater debt burdens or shift responsibility for finance onto vulnerable countries, should not be considered as contributing toward the floor of US$400 billion per year.”

A paper by CEEW recommends that the L&D Fund sit alongside, but distinct from funding mechanisms like the Green Climate Fund and the Global Environment Facility, and that it be deployed exclusively for loss and damage. Grants and unconditional transfers are preferable financing instruments. The money, it emphasises, should be new, additional, predictable, adequate, fair, debt-free, and accessible to all developing countries.

The role of the World Bank:

Another point of contention is the appointment of the World Bank as interim trustee and host of the fund’s secretariat for the first four years. Developed countries, such as the US and EU member states, rooted for the World Bank on the grounds that it would speed up operationalisation of the fund. However, 68 organisations have expressed disapproval over the bank’s trusteeship, sceptical of its ability to administer the fund fairly, concerned about the influence that the US, which appoints the bank’s president, may have on its decisions, and wary of the unjustly high interest rates it has charged developing countries in the past. In addition, the bank charges exorbitant administrative fees, which can vault up to 20 percent of a fund’s flows.

Concerns have been allayed by reassurances that the bank will, over this interim period, be closely scrutinised for accountability, transparency, and fair play. In the meanwhile, the World Bank is yet to accept all the conditions to trusteeship laid down in the decision text. Disputation over any condition can stall the implementation of the fund even further.

Is India eligible for this money?

Advanced economies like the US, as well as Small Island Nations, have insisted that India and China also contribute towards reparative climate finance. India is the world’s fifth largest economy, with a GDP of USD 4.11 trillion (one spot ahead of the UK), but it still counts itself as a developing country. India is the third largest greenhouse gas (GHG) emitter after China and the US, with 3,380 metric tons of carbon dioxide-equivalent (MtCO2e) released in 2019. However, in per capita terms, the country ranks 10th in global emissions with 2.5 tCO2e per person. The global average is 6.5 tons; the US leads with 17.6 tons per person.

As an emerging economy with the world’s largest population, and having started down the road to industrialisation two centuries after Europe and the US, India has argued that it cannot be held to the same funding benchmarks as historical emitters. Moreover, like other developing countries, it too has suffered catastrophic climate impacts: in 2019, it lost nearly USD 69 billion to climate-related events. The Reserve Bank of India, citing secondary research, projects that climate change could cost the country 2.8 percent of its GDP and depress the living standards of nearly half its population by 2050. A recent district-level assessment of climate impacts claims that 80 percent of India’s population lives in districts that are highly prone to extreme weather events.

Yet it’s unlikely, observes a TERI report, that India stands to benefit from the Loss and Damage Fund anytime soon, given the size and scope of the money pledged. But it can leverage its position as a political and economic heavyweight to shape the narrative around how and where the money will flow.

Joeanna Rebello Fernandes and Shreya Adhikari contributed to this article with inputs and insights from Pranav Garimella, Programme Manager – Climate Program, WRI India.

—

Know more

- Learn about rural mitigation measures for water scarcity in this photo essay.

- Watch this video to learn more about loss and damage.