My name is Chatar Singh, but everyone affectionately calls me Chatru. I am from a village called Devdungri, located in Rajasthan’s Rajsamand district. I live with my parents who work as daily wage labourers under the MGNREGA scheme. Most people in Devdungri either work as labourers or migrate as the village doesn’t receive enough rainfall for agriculture to be a viable option. Although we’re a family of seven, my sisters moved away from home once they got married and my brothers also ended up migrating to earn.

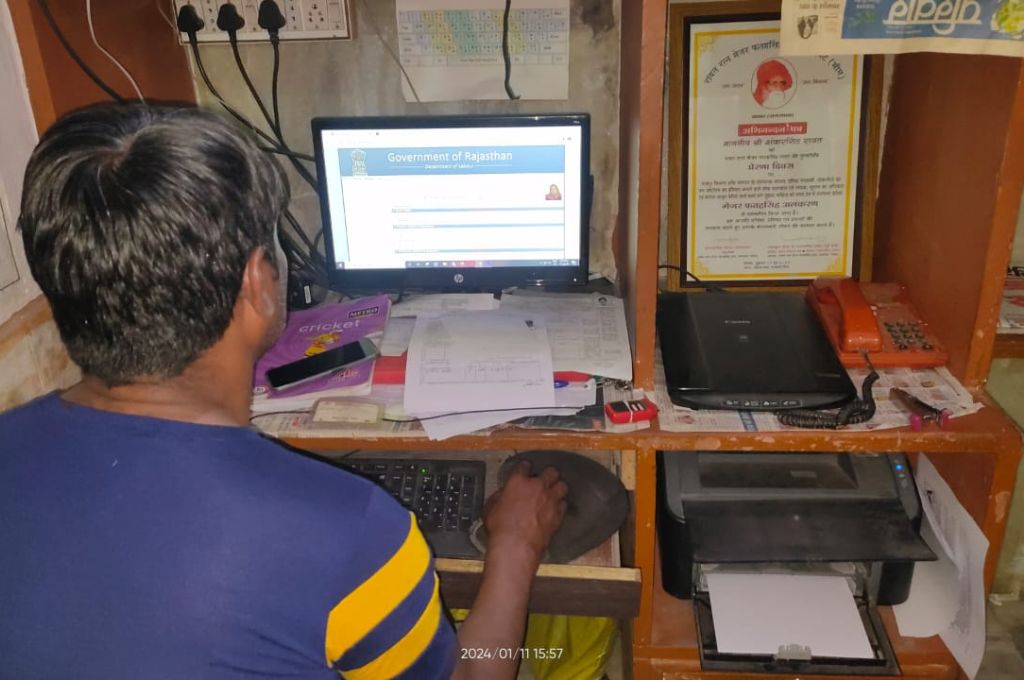

I work as an eMitra, which is a platform as well as a job role—an eMitra is someone who enables people in Rajasthan to apply for government-mandated schemes and services online. In my work, I use the Jan Soochna Portal—a public information portal operated by the Government of Rajasthan and updated in real time—to track people’s entitlement delivery and application statuses. I work with the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS)—an organisation that was founded in Devdungri itself. Our household is run by my parents’ income and the minimum wage of INR 289 per day that I receive working as an eMitra with the MKSS.

When I was seven or eight years old, an unlicensed medical practitioner gave me an injection in the leg, which hit a nerve that it shouldn’t have. It ended up giving me a permanent physical disability. Due to societal superstitions, no one connected my disability to the injection. On the contrary, people thought that I had been possessed. I was not taken to a hospital in time to get the right treatment. Instead, I was taken to a temple, where the local priest kept giving my family false advice—telling us to come back after 2 months, then 4 months, and so on—while making empty promises that I would get better. Two to three years passed in this way, after which no doctor was able to fix the damaged nerve. This disability hindered my quality of life, and while my older brother taught me at home for some time, I didn’t receive any formal education until I was 10 or 11 years old.

I studied at a school in Devdungri till standard 12 and then completed my graduation through distance learning. But when it came to studying for my second undergraduate degree, for which I had to attend classes in person, my mother didn’t want me to leave home. She was worried that there would be no one to take care of me and that I wouldn’t be able to manage alone. I got into arguments with her—I understood her concerns, but I wanted to get out of the house and experience the world. I have often seen people with disabilities become restricted to the four walls of their houses. I did not want that to be my reality.

Over the years, I learned to walk, and even travel. That is how I was able to pursue higher education. My work as an eMitra brings me great meaning by allowing me to help other people, many of whom come from low-income backgrounds and are often unable to access government social entitlements and benefits by themselves.

3.30 AM: I wake up early and for two hours I study for various competitive exams, ranging from the Rajasthan Eligibility Examination for Teachers (REET) to the Rajasthan Administrative Services (RAS). It’s my dream to become either a teacher or an RAS officer and provide financial stability to my family. I really enjoy learning and have completed a BEd degree and three master’s degrees. Since I couldn’t get out of my house and attend school till standard 5 because of my disability, I understand the value of education.

Not being able to attend school wasn’t my sole obstacle though—taboo and superstition have followed me for most of my life. Villagers considered seeing me in the morning as a bad omen. My family, especially my mother, had to hear jibes such as, “Send him out after 10 or 11 am. He brings bad luck if we see him first thing in the day.”

But ever since I started working as an eMitra, there has been a shift in the community’s behaviour towards me. The very same people who used to shun me for my disability now wait outside my house in the early hours to ask about the status of their pension, ration, and other social entitlements.

I am happy to help them because I strongly link my work to social service. Supporting and informing people about their entitlements is integral to them realising their rights. For example, an old widowed woman living in poverty came to me because she was not receiving her pension. Though she was eligible for an old-age pension as well as a widow pension, she was not literate and so unable to complete the required paperwork. I filled out her pension form, filed for a job card for her, and tried to get her name added to the National Food Security Act scheme. Ideally, she will receive the benefits from these schemes for the rest of her life. I attend to approximately 50–60 such people on a daily basis at my eMitra centre.

The office opens at 9.30 so I have breakfast and leave for work by 9 am.

9.30 AM: The eMitra’s room is in the MKSS office in Rajsamand’s Bhim tehsil. Our office is called the ‘Godam’, or warehouse, and it is situated between four districts—Rajsamand, Pali, Ajmer, and Bhilwara. People from all these districts visit my office. My work is mainly online, where I help people apply for and follow up on government benefits and make them aware of the various Rajasthan state government schemes for which they are eligible.

The Rajasthan government has set a fixed minimal rate of INR 50 per service in our area. However, I have seen many eMitras charge more than this amount—as high as INR 100–150—even though they give the person a receipt of INR 50.

The bigger concern is the corruption prevalent in the system. I have observed eMitras take advantage of those who are supposed to receive entitlements. For example, a person who holds a labour card under the Building and Other Construction Workers Act, 1996, can avail of the Shubh Shakti Yojana, wherein their daughter receives INR 55,000 from the government if she is unmarried at the age of 18 and educated till at least standard 8. Many people get duped by eMitras who tell them that they could help them obtain their INR 55,000 sooner provided they get a cut of INR 10,000 or INR 20,000. People agree because the eMitra has connections with dishonest officials of the department, and the application form for the scheme is processed quickly. Else, the process—from the application stage to receiving the entitlement—can be very slow.

Even our centre was started as a counter to the corruption in the system. When I had started working at the MKSS office back in 2014, we found that a woman had been made to pay INR 200 instead of INR 20 by an eMitra centre. Because I couldn’t help much on the field, I was given the responsibility to run a model eMitra where people would be charged with the appropriate amount only.

1.30 PM: My colleagues and I take a break to cook and eat lunch together at the Godam. We talk about many topics, ranging from our personal lives to politics. We often discuss accountability and the fraudulent practices present in delivery mechanisms as the links between the eMitras to local officials in various government departments further exacerbates the problem.

The Rajasthan government provides more than 600 services and schemes that can be accessed through eMitra. We have organised three jan sunwais (public hearings) in the past to figure if the right people are receiving the benefits of these schemes. We conduct a social audit in the village to understand what stage each person is at in getting their entitlement. We then bring the entire village and department officials together in one place for a public hearing and rectify any errors in the execution of a scheme for each person. For example, if we’re doing a jan sunwai for the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana, we’ll identify the problems the people are experiencing and the relevant department can work on correcting the mistakes. It helps us understand if someone has wrongfully received money and we can hold officials accountable for it at the same time in front of the entire village.

5.00 PM: I usually work till 5 or 6 pm. Processing an application can take me anywhere between 30 minutes to an hour because it’s important to fill all the details carefully. I didn’t receive any proper training to render the services so I either rely on YouTube or learn through trial and error.

Because we have access to all the relevant information through the Jan Soochna Portal and fill multiple forms for a person, we can catch mistakes. I remember when a couple years into working as an eMitra, a woman came to us to inquire the status of her pension—it had been months since she had last received an instalment. I checked the records and realised she had been declared dead in the records because of unverified documents. Upon digging deeper, we learned that approximately 6–8 lakh people had been declared dead in Rajasthan when they were, in fact, alive. In such situations, it’s helpful to have connections with those employed in the technical arm of the government as well as officials at various levels so that we can contact them directly. We consulted the sub-divisional magistrate (SDM) and block development official (BDO) to highlight this case and find a solution. I have always associated our work with the government—they cannot function without us, and we cannot function without them.

After work, I sometimes get called for trainings or other meetings. For instance, I closely collaborate with the School for Democracy, an organisation dedicated to democratic and constitutional rights and values. They invite me for workshops to familiarise individuals with important schemes in Rajasthan and educate them on how to use the Jan Soochna Portal. I also conduct sessions with the youth to sensitise them to the discrimination faced by persons with disabilities.

I even tell the parents whose children have disabilities to not restrict them to the home. Instead, children should be encouraged and given the opportunity to do something with their life. Without education, my life would have looked very different, and the taboos associated with me in childhood would have followed me my entire life.

7.00 PM: I reach home and watch television for an hour or so. I really enjoy watching cricket and was quite disappointed when India lost the 2023 World Cup. Other than that, I watch CID. It gets dark here quite early, so I have dinner before 9 pm. Since I don’t get the time to check my phone during the day, I reply to messages and fall asleep soon after as I have to wake up early in the morning to study.

As told to IDR.

—

Know more

- Read about a day in the life of a Haqdarshika, who delivers citizens’ rights to their doorsteps.

- Read about what’s missing in government’s plan to secure accessibility for persons with disabilities.