When EdelGive Foundation decided to do more to advance the education of rural Maharashtra’s 16 million elementary school children, CEO Vidya Shah and her colleagues knew that the foundation alone lacked the financial resources and on-the-ground presence to accomplish this enormous goal. Undaunted, in 2016, EdelGive embarked on a bold and innovative solution: it formed The Collaborators for Transforming Education, a public-private partnership that currently comprises seven primary funders, two operating partners, and the state of Maharashtra’s Department of School Education and Sports. Collectively, they have reached 1.3 million students so far.

The Collaborators are just one example of a small but growing trend in India toward philanthropic collaboratives. We define them as entities co-created by three or more independent actors (including at least one philanthropist or philanthropic institution) who pursue a shared vision and strategy for achieving social impact, using common resources and prearranged governance mechanisms. In increasing numbers, Indian funders, government, nonprofits, and intermediaries are joining forces to address the array of climate, economic, social, and other looming problems faced by the country. “If we want to do scale-related work, the only way forward is through collaboratives,” Shah says. “There is no other option to tackle these big social problems.”

The Bridgespan Group’s recent research, detailed in Philanthropic Collaboratives in India: The Power of Many, found that most Indian collaboratives are less than five years old. Given their promise, why has there not been more formal collaboration to address complex social change?

Call it the ‘collaboration conundrum’. Social sector actors understand in theory that they benefit by drawing on others’ resources, skills, and experiences, but relatively few do so because it can be difficult to build consensus across multiple partners, accept the risk that some partners might fail to deliver, or share credit for their work.

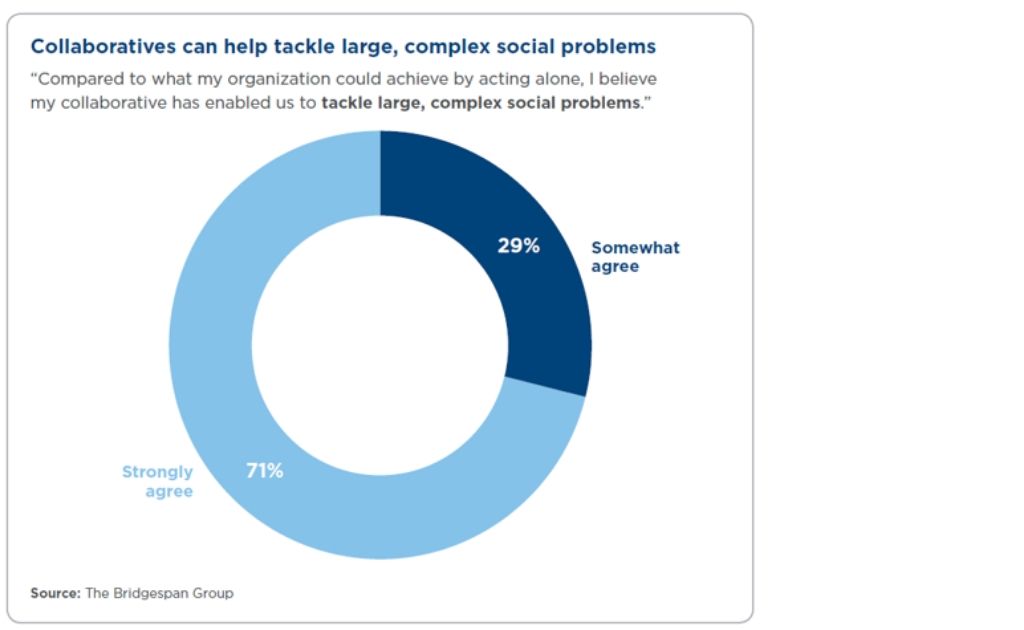

Nevertheless, our survey of multiple stakeholders affiliated with 13 Indian philanthropic collaboratives and more than 50 interviews found that for a large majority of these unions, the benefits of working together outweigh the risks. Indeed, 71 percent of the 35 survey respondents strongly agreed that collaboration has enabled them to make more progress toward addressing India’s socio-economic challenges, than working alone has.

The organisations surveyed also identified three primary motivations for working collaboratively:

- by leveraging the diverse skill sets of different partners, the total effect can be greater than the sum of its parts;

- it expands the circle of influence, and the impact of individual participants; and

- it mitigates risk by spreading it across multiple players.

Despite the benefits, our research found that participants in a philanthropic collaborative often encounter unique hurdles, including:

- finding long-term funding, balancing the organisation’s priorities with those of the collaborative;

- overcoming a lack of trust, or clarity among the partners; and

- adapting to working in the collaborative model.

As more funders and stakeholders shift from considering partnering to actually pursuing it, philanthropic collaboratives will become the new normal for taking on complex issues. | Picture courtesy: RawPixel

There is no one-size-fits-all solution for avoiding these pitfalls, and they vary in severity in the different life stages of the collaborative. Nonetheless, our study helped us identify ‘3Cs’ that current and aspiring collaborators might keep in mind:

- It takes commitment to collaborate. Making progress toward large goals requires a significant investment of time, imagination, and persistence. It helps to recruit funders who are willing to provide long-term, unrestricted funding. For example, The Collaborators partner only with organisations that buy into the pooled funding model and truly share the organisation’s mission and strategy for driving impact. “It is why we have only seven funders,” says Naghma Mulla, EdelGive Foundation’s chief operating officer.

- Clarity (and communication) can streamline collective action. This requires regular conversations about who does what within the collaborative, as well as on how core and implementing partners are faring against the commitments they have taken on. To ensure that roles and responsibilities were clear, 10to19: Dasra Adolescents Collaborative formed discussion groups that met frequently and defined the work of each operating partner.

- Be prepared to course correct. Some assumptions may not prove out. By tracking progress and results, collaboratives can learn, improve, and make any changes necessary to meet their goals. When The Education Alliance suddenly lost two funders, it brought in new core partners and acquired new funding. It also transitioned from a collaborative to a nonprofit entity while remaining committed to its mission: ensuring quality education for children in government-run schools.

Although philanthropic collaboratives in India are a relatively new phenomenon, interest in them is accelerating. During the course of our research, we found that some global collaboratives, as well as domestic philanthropists, are actively considering setting up collaboratives in India. Over the next five years, as new collaboratives emerge and existing collaboratives produce far more outcome data, we will learn much more about their impact.

Players in the social sector will have to recognise the potential of collective action—and have the perseverance to keep at it.

What is already clear is that as more funders and stakeholders shift from considering partnering to actually pursuing it, philanthropic collaboratives will become less of an exotic pathway in India’s social sector, and more the new normal for taking on specific, complex issues. That means players in the social sector will have to recognise the potential of collective action—and have the perseverance to keep at it.

“We need to think more deeply about how we can get more people to work together,” says Ajay Piramal, founder of Piramal Foundation. “Collaboration requires a long-term commitment. The problems we face will not be solved in one or two years.”

The research on philanthropic collaboratives builds on the work of Bain & Company, Dasra, and EdelGive Foundation, as well as Bridgespan’s 2018 study Bold Philanthropy in India: Insights from Eight Social Change Initiatives and its Conversations with Remarkable Givers.

—

Know more:

- Understand in depth how philanthropic collaborations succeed and why they fail.

- Read this piece on the power of collaboration among philanthropic, government, and corporate ecosystems for positive outcomes in education.

- Read the reports Collaborative Action and Collaborative Force to comprehend the vital role of collaboratives in advancing India’s development agenda.

Do more:

- Connect with the authors Pritha Venkatachalam and Kashyap Shah.