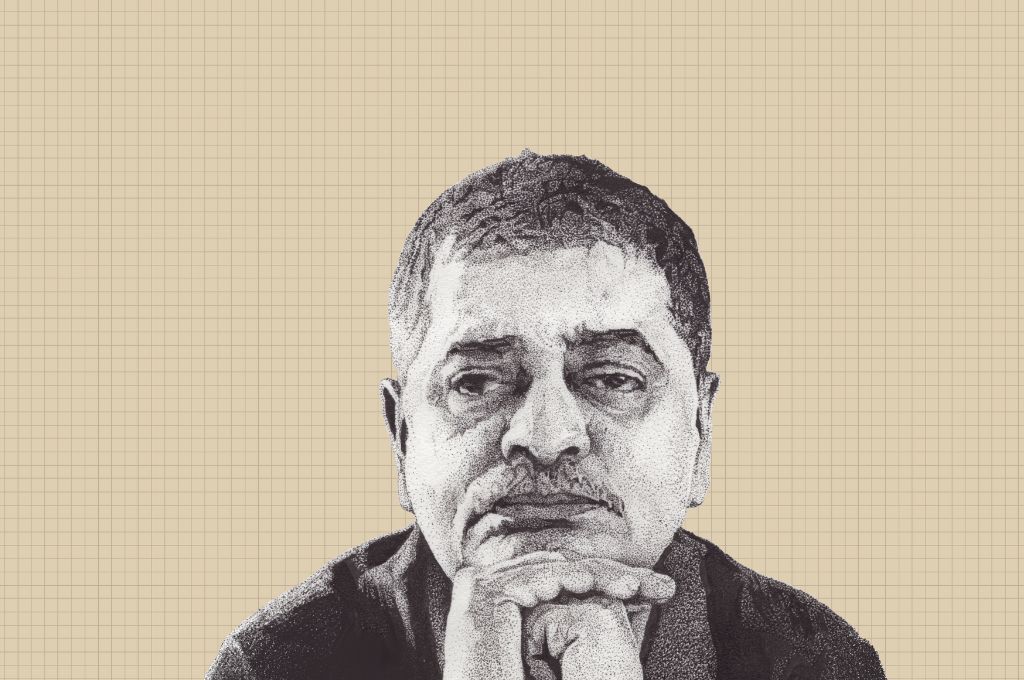

Activist, humanitarian, and writer, Xavier Dias is a name familiar to most Adivasis in Jharkhand. An integral part of the Jharkhand statehood movement, he was also a key leader in the fight against uranium mining in the state. At 67, Xavier has spent most of his adult life working closely with Adivasis, helping them secure and safeguard their land, labour, and human rights, and raise their political consciousness.

In this interview with IDR, he discusses his role as an outsider living and working in Jharkhand, shares his perspectives on the nature of development and reflects on what the future holds for the Adivasi people.

What were some of the early influences in your life?

I grew up in Bombay—I lived in Dadar, in the heart of the textile mills. My father ran a night school for textile mill workers and I did my primary schooling with them—I learnt alongside these older, married men.

I came from a completely different community—the Bombay Catholic community—fun-loving and apolitical. They didn’t know about the working classes, they didn’t know about Dalits and Adivasis; I didn’t know anything about them either. But seeing these workers come to class after a hard day’s work—it had a big influence on me.

Soon after, I went to university in Bangalore in the late sixties, and I was fortunate enough to join a group of students who were politically very sharp. And left-thinking.

We told ourselves we had two options—either join institutions that are against the people, or be with the people.

India, in the early seventies, was living ‘ship-to-mouth’. The US was sending grain to India; we had to stand in long ration lines. Kerosene was underground and by the time it was 1975, even matchboxes were on the black market. The Naxalite movement was also growing and there were many global events unfolding at the time—the Bangladesh Liberation War, Mao Tse Tung’s barefoot revolution in China, and the Vietnam War—that influenced us.

As students we did our homework: if you were a graduate, you were part of three percent of India’s population (India’s population was 500 million at that time). If you had a bank account, you were part of the five percent. Knowing this, we told ourselves that we had two options—either join institutions that are against the people, or be with the people.

Many of us decided that we should go and identify with the masses. That gave us our political framework. What was the point of having a job, a car, a wife and two children—would we be happy knowing that the money we got for this had made someone else poor? We were very ambitious and also very naive.

After I graduated I started working with AICUF—a national student organisation, as their National Programme Secretary, travelling to different universities across the country organising students. I made my way to Jharkhand, which was still South Bihar at that time. I lived in an Adivasi student hostel, where the conditions were terrible. It was overcrowded—three boys sleeping on a bed; there was no access to running water, two meagre meals were provided daily, and they were grossly inadequate—a few grains of rice, some dal and a chilli. The girls’ hostel was even worse. They had toilets, but no doors.

Shortly after I arrived, Emergency was declared and many of us went underground. In those days, anyone picked up on charges of activism (or suspected of Maoism) was unlikely to come out alive, so we disappeared into the forests for almost two years. After the Emergency ended, I started working with miners, helping them organise themselves.

Could you tell us more about the situation in the mines?

We were working in small, private mines, with one to two hundred labourers. We discovered that the workers in these mines were actually the original owners of the land where this mining was taking place.

From 1977 till today, over 200 people I know or have worked with, were either killed or died of curable diseases. None of them, except one, crossed the age of 45. All were Adivasis.

The mining companies were all owned by outsiders—mostly Marwaris, Biharis or Bengalis. They would come and take a thumb impression of the Adivasi land owner on a blank paper and tell them “we’re giving you a job in the mine”. And since the Adivasi peoples’ fields had been destroyed, they were forced to work in these mines in very dangerous conditions. They weren’t paid the minimum wage—they received two rupees per day for ten hours of back-breaking and risky work; there were no maternity benefits; and men and women did not receive equal wages.

We also organised labour in the crushing plants, where workers were breathing in silica dust all day long. There was no protective gear provided and many of them died from silicosis. One of these plants employed 27 young Adivasis. In less than ten years after we started working with them, 26 of these Adivasi workers had died. Not a single one of them reached the age of 30. The one person who survived had left the plant to work at a printing press.

Management reacted by registering cases against us. We used to go in and out of jail; they tried to assassinate us, but we managed to survive. I wasn’t alone; there were hundreds of us. From 1977 till today, over 200 people I know or have worked with, were either killed or died of curable diseases. None of them, except one, crossed the age of 45. All were Adivasis.

What motivated you to devote your life to working with Adivasi peoples?

I stayed on in Jharkhand because I fell in love with the people and perhaps more importantly, because they allowed me to stay. I had to learn everything. Unlearn and re-learn. In the 45 years that I’ve been an activist, I’ve spent most of my time unlearning and re-learning.

In the 45 years that I’ve been an activist, I’ve spent most of my time unlearning and re-learning.

My focus was on labour and land rights. I worked to raise the Adivasi peoples’ political consciousness. They are very aware of their ‘Adivasiness’. They were already organised, by systems of governance that go back thousands of years, and that are much more evolved than our modern systems of democracy.

My role, as an outsider, was to help the Adivasi peoples connect the problems that they were facing with the outside world and to use language that they were familiar with to help them understand their rights and the tricks or strategies of their oppressors. I spoke English, which was an added advantage. In anything that we did, we tried to empower their ‘Adivasiness’.

The Adivasi peoples are critical to our future. When the future world wants to learn how to live in communities, to live in forests—in a symbiotic relationship with nature, they will look to these communities if they are still there.

What does development mean to you?

The development that people talk about—our middle and urban classes don’t understand what it really means. For them it’s about ‘the Adivasis are sitting on iron ore, coal, uranium. Why can’t they sell their land—it’s a win-win situation.’ Till now, nobody has become a millionaire by selling their agricultural land or mining on their land.

“We discovered that the workers in these mines were actually the original owners of the land where this mining was taking place. The mining companies were all owned by outsiders.” | Photo courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Imagine that you live in Malviya Nagar, New Delhi. And the government finds gold beneath your land. They will requisition your home and land and give you compensation. You can go to another part of the city and buy a house there. That is called relocation. But what if they gave you a wooden plank, with some Bisleri water, a bundle of money notes and leave you in the middle of the Arabian Sea. That is what displacement looks like for the Adivasi peoples.

In Bombay electricity is available with the flick of a switch and you take it as a right, as an entitlement. But does anyone think about what it really costs?

They don’t have much of a choice; they have to leave their lands and go to the mines or bastis. Most of the mining towns don’t have sewage treatment plants, and all the sewage is released into the surrounding rivulets and rivers, which in turn are sources of drinking water. The women and children suffer the most—in the millions. And nobody knows. In Bombay electricity is available with the flick of a switch and you take it as a right, as an entitlement. But does anyone think about what it really costs?

Today, the Adivasi peoples have no alternative but to march towards modernity. And as they do so, they will have to decide what they choose to retain or give up. Much of what mainstream society offers them is taking a toll on their health and they face lifestyle diseases, for which they cannot afford the cures. But we cannot decide on their behalf. It is their democratic right to join the mainstream and we cannot stop them from doing so.

The younger generation is migrating to urban areas. There is really nowhere else for them to go. Once they graduate from high school or college, it is very difficult for them to go back to their villages, so they stay on in the towns and cities, often preparing for UPSC and other exams—they call it ‘taiyaari’. But this rarely translates into jobs.

Those that have chosen to stay behind live off their land—it sustains them with food, water, fodder, and fuel. In recent years, some Adivasis have taken to organic farming and mushroom cultivation and this seems to be a growing trend. Since there are no jobs available, the Adivasi peoples’ land plays an important role in their survival.

How would you like to be remembered?

As an individual, I have no desire to be remembered. I want people to remember how we saw the problem and how we tried to tackle it, to understand the history of the problem, and the history of the methods the people used to address it. But as a person, as Xavier Dias, I don’t want to be remembered.

I stopped working ten years ago for two reasons primarily: I have a chemical imbalance in my brain caused by radiation—from having worked in the uranium mines over the last several decades. But more importantly, I stopped because I saw that I was no longer needed—the Adivasis are able to lead, manage and grow the movement on their own.