This article was written as a response to the draft National Education Policy (NEP) announced in 2019. You can read about NEP 2020 here.

The government’s draft New Education Policy released in May 2019 suggests increasing spending on education from 10% of total government expenditure to 20% by 2030. However, there is no funding available for such an increase in India’s current education budget.

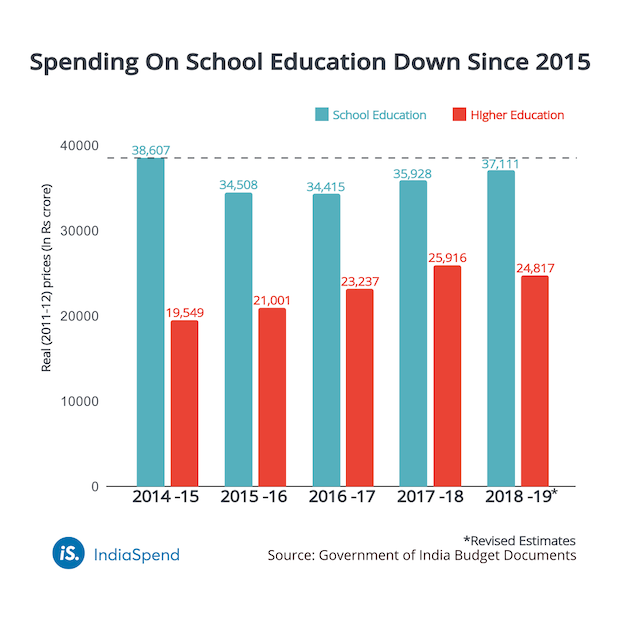

Further, since 2015, government spending on school education has actually decreased after correcting for inflation, according to an analysis of state and central education finances over the years.

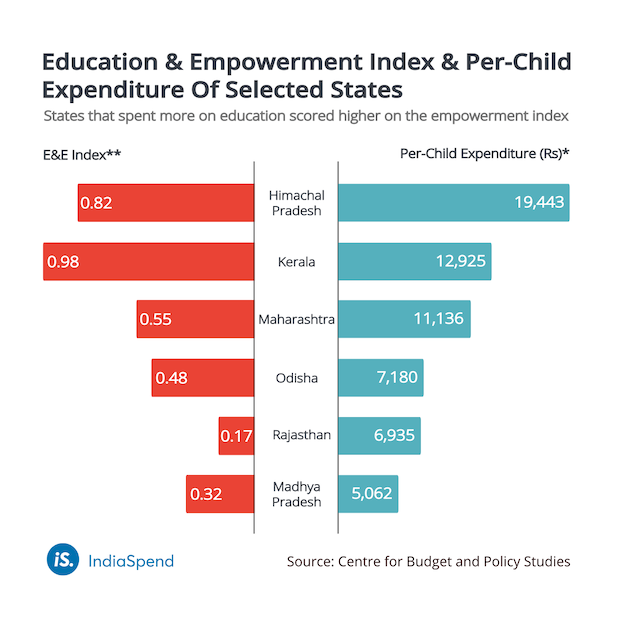

Good public education is a fundamental right in India, and there is a strong correlation between public investment in education, child development and empowerment. For instance, states that spent more on education, such as Himachal Pradesh and Kerala, scored higher on the empowerment index, which takes into account attendance levels at primary, upper primary, secondary and senior secondary levels, as well as indicators linked with gender equality such as sex ratio at birth and early marriage.

*Year: Average expenditure on school education for the period 2012-13 to 2018-19. **Note: This is computed by the Centre for Budget and Policy Studies taking six indicators (four relating to education and 2 relating to empowerment, sourced from National Sample Survey Office’s 71st round and National Family Health Survey, 2015-16, respectively)

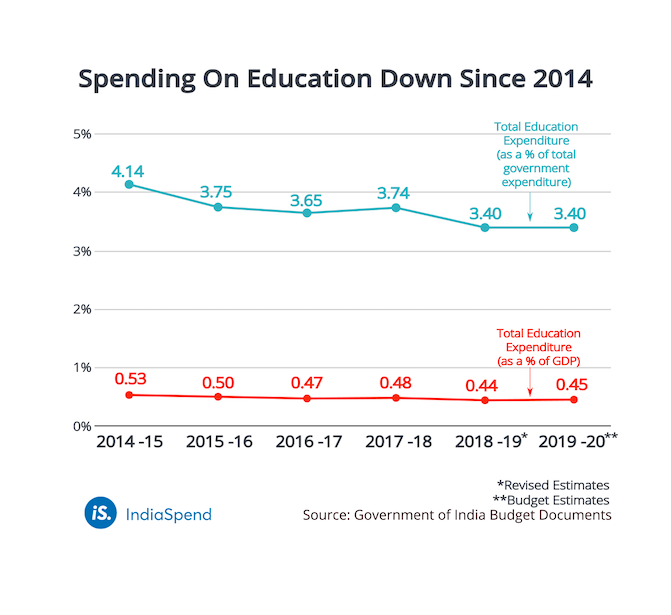

Central government’s education budget reduced since 2014

Even as the government promises an increase in spending on education, the share of the union budget allocated to education fell from 4.14% in 2014-15 to 3.4% in 2019-20, the period during which the Bharatiya Janata Party headed the central government, according to budget documents from 2014 to 2020. In the 2019-20 budget, the share of the union budget allocated to education remains at 3.4%, which means that, this financial year, the government is not allocating more money to education as the new education policy would require.

It is not only the share that has declined; in case of school education, the budget has decreased in absolute terms. Total money allocated to school education reduced from Rs 38,600 crore in 2014-15 to Rs 37,100 crore in 2018-19, based on the budget’s revised estimates.

To match the goal of spending 20% of the country’s government budgets on education, states would also have to increase their spending. Currently, the bulk of education spending (between 75-80%) comes from the states, as the draft new education policy reports.

The proportion that states spent on education reduced in several states, especially after the 14th Finance Commission period of 2015-16 to 2018-19. The allocated funds increased in 2019-20 but the actual expenditure will only be known in the 2020-21 budget. The education policy does not clarify how states would increase this share without any additional central government funding.

For instance, an analysis of school education expenditure for eight years from 2012-13 to 2019-20 shows that education expenditure declined as a percentage of total government expenditure in six states–Kerala, Maharashtra, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Himachal Pradesh, according to budget documents.

The decline (from 16.05% of the expenditure of six states, on average, in 2014-15 to 13.52% in 2019-20) started from 2014-15, the first year when fund transfers from the union government for centrally sponsored schemes was routed through the state budget. The decline continued during 2015-16 which was the year when the state’s share in taxes increased, while the tied funds through centrally sponsored schemes decreased, as recommended by the 14th Finance Commission.

There has been a slight increase during 2018-19 and 2019-20 in the amount these six states together allocated to education over the last two years, but these numbers are budget estimates and not actual spending, according to budget documents from these states.

States have reduced the share of funds spent on school education, even as government revenue has increased. For instance, Kerala’s share of spending on education reduced from 14.45% of the total public expenditure in 2012-13 to 12.98% of the total state budget in 2019-20 even as its revenue grew at a compounded annual growth rate of 12.8% during the same period, an analysis of state budget documents shows.

Five out of six states–Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Maharashtra and Odisha–have increased staff salary during this period. Had there been no pay hike, this decline would have been even sharper than what is observed now.

Is a 20% increase in the education budget needed across all states?

While the transfers of tax shares determined by the finance commission formulae are transparent, transfers through the union budget for centrally sponsored schemes, including programmes for education, are rarely put in the public domain, and are difficult to evaluate. That makes it difficult to fully understand the rationale, fund flow and priorities for education.

A blanket recommendation for all states does not take into account the variation that exists among Indian states.

A blanket recommendation for all states does not take into account the variation that exists among Indian states. Currently, a number of states already spend something between 15% and 20% on education. The economically advanced states spend a lower percentage of their total expenditure on education but that still amounts to a higher per child expenditure because that government is richer.

In addition, pushing economically advanced states to spend more on education does not necessarily help, as there is a greater need for investment in the poorer states, and every state has a different capacity to spend.

A bigger GDP, corporate funds, are unlikely to bridge the funding gap

The education policy says that public expenditure on education will increase as India’s gross domestic product (GDP) increases, even if the proportion spent on education remains the same. But the policy mentions a GDP of $10 trillion by 2030-32, which does not seem to be viable given the slow pace of the economy, substantially lower central government tax revenue collection, and no sign of recovery of domestic investment.

The policy then makes a case for philanthropy, including Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), for funding public education. Despite 37% of all CSR money being spent on education in 2016-17, it amounts to only about Rs 2,400 crore, which is less than 0.5% of the total spending by the central government alone. The share will be less than 0.1% if one takes the entire public funding on education by the union and state governments into account.

Further, for philanthropy to exactly match the needs of public education, the government would need to synchronise philanthropic spending with policy goals, and also develop some system of accountability to ensure the quality of work. Still, CSR will not substitute public expenditure as it will continue to be small in comparison to the country’s needs and it will not be spent where it is most needed.

For instance, there is little funding for undergraduate colleges in remote locations. Existing education projects are almost entirely confined to school education, as this news article on CSR funding by The CSR Journal shows.

Historically, in countries where philanthropy has helped in widening the base of education, it has been guided by two motivations: religion (e.g., Christianity and Islam promote charity) and inheritance tax, research at Centre for Budget and Policy Studies shows. India has abolished inheritance tax and there are many issues associated with religious institutions funding education, such as what powers it gives that particular religion to influence curriculum or the choice of subjects.

The education policy also recommends local contributions but given the stratified nature of Indian society, in terms of caste, class, gender and religion, such local contributions might increase inequality in access to education.

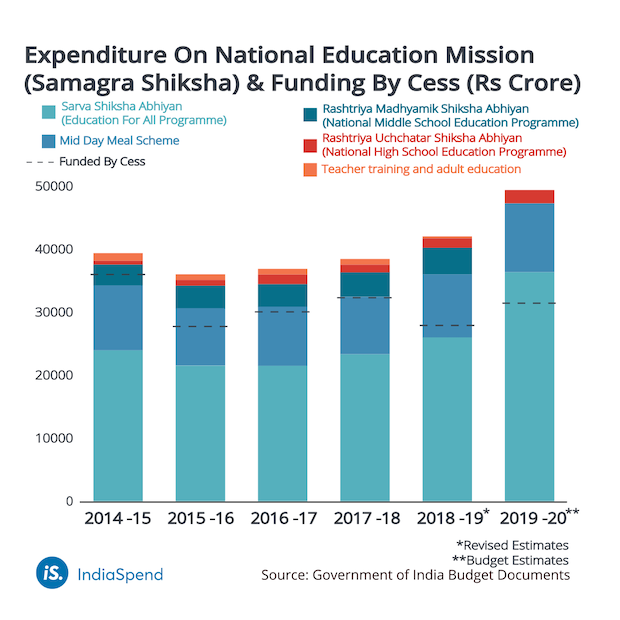

Government education funding overly dependent on the education cess

The Indian government introduced a 2% education cess in 2004 which was initially used to fund the universal midday meal in public schools. In 2007-08, the government introduced a 1% secondary and higher education cess. In 2018-19, the education cess as well as the secondary and higher education cess was revamped into a health and education cess at 4%. In 2018-19, the government introduced a new social welfare surcharge of 10% on aggregate import duties.

A cess is a dedicated fund for a purpose, and in this case the education cess is expected to cushion the government’s education expenditure. The dedicated fund is transferred into non lapsable funds–the Prarambhik Shiksha Kosh (primary education fund) and the Madhyamik and Ucchahtar Shiksha Kosh (middle and upper education fund). Information on the primary education fund is available in public accounts, but there is no information of the middle and upper education fund.

The cess is not a permanent source of revenue to the government. It is only to aid and to cushion the expenditure sourced from tax revenue/budgetary support. As the total budgetary support for education expenditure has declined, the cess has funded 70% of the total education expenditure since 2015. This means that the cess has become a regular way of funding education expenditure rather than providing the money through a dedicated budget.

Based on the assumption that at least half of the education and health cess is being spent on education and a third of the surcharge is spent on education, these two taxes together would be funding about 64% of the budgeted estimates this year.

Cess and surcharges are tools of revenue collection for specific purposes, and are not part of the divisible pool, which means that while the union government is using this cess to fund their part of the education budget, state governments have no say or access to this fund. None of these issues are discussed in the education policy.

Note: Only 50% of the cess collections has been considered since 2018-19, since the cess is for Health and Education together

Higher education funding focuses on few institutions

In funding higher education, the largest share goes to premier institutions such as Indian Institutes of Technology, Indian Institutes of Science Education and Research and central universities. There is little push to widespread undergraduate education.

Further, the budget has allocated Rs 130 crore in 2019-20 for the promotion of technology-based online courses, but recent research on open schools in India and research from across the globe on technology-based education shows that literacy levels, access to and ease with technology, and the presence of a self-learner who decides for herself and acts on her own, have an impact on learning digitally. In India, such an approach will have a limited impact given class, caste and gender barriers to using technology. The use of such technology is biased towards urban, upper caste males, according to research on open and distance-based schooling in India by the Centre for Budget and Policy Studies.

This story was originally published on IndiaSpend, a data-driven, public-interest journalism nonprofit.