104 million tribal people, accounting for 8.6 percent of India’s population, are heavily marginalised and discriminated against. Not only are tribal communities socio-economically othered by the mainstream Indian populace, they also face a host of structural inequalities, with access to healthcare being one of the biggest.

While there seems to be a vague consensus amongst policymakers that tribal communities have poor health and restricted access to healthcare, there are still no comprehensive policies that meet this need, and no reliable data about the state of tribal health. Tribal healthcare in India usually falls within the ambit of rural healthcare. The assumption that the problems and needs of tribal people are the same as that of rural populations is incorrect; the difference in terrain, environment, social systems and culture, all lead to tribal communities having their unique set of healthcare needs.

To address this, The Expert Committee on Tribal Health, headed by Dr Abhay Bang, was created. This led to the examination of how tribal people in India suffer from inequity in health, and how this gap can be bridged.

Related article: The ecology of an itch

Over four years, the committee studied the health issues, culture around health, and healthcare infrastructure present in tribal areas, and sought potential ways forward through a consultative process with researchers, representatives of tribal people, and other experts. The result? This report—Tribal Health in India—Bridging the Gap and a Roadmap for the Future—the first of its kind in India.

Here’s an overview of some of the findings:

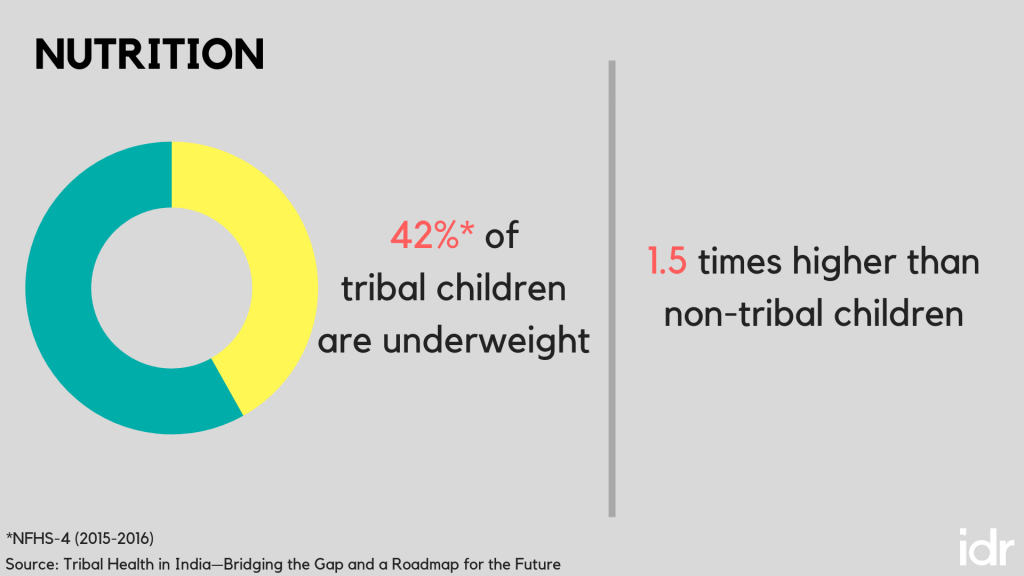

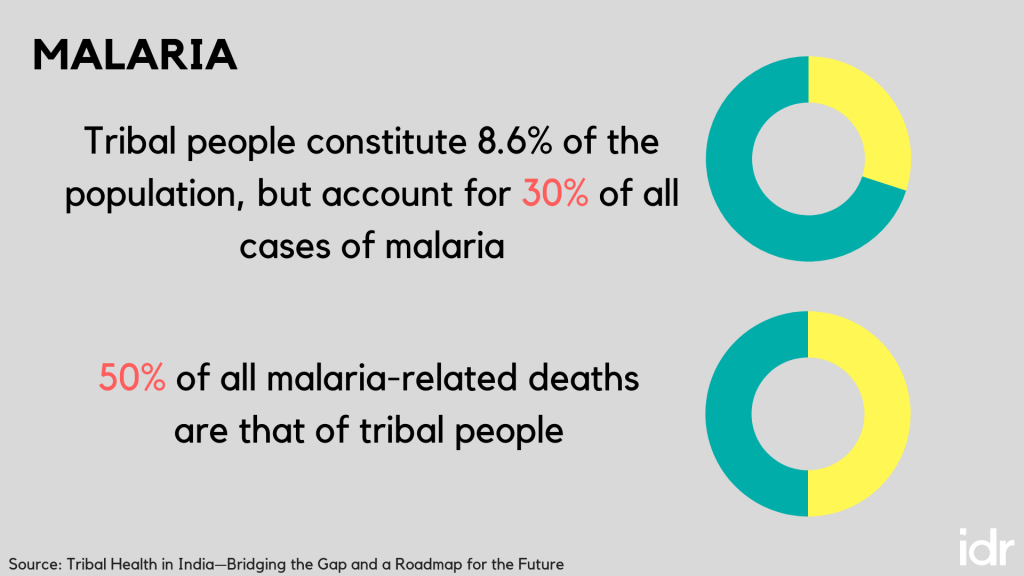

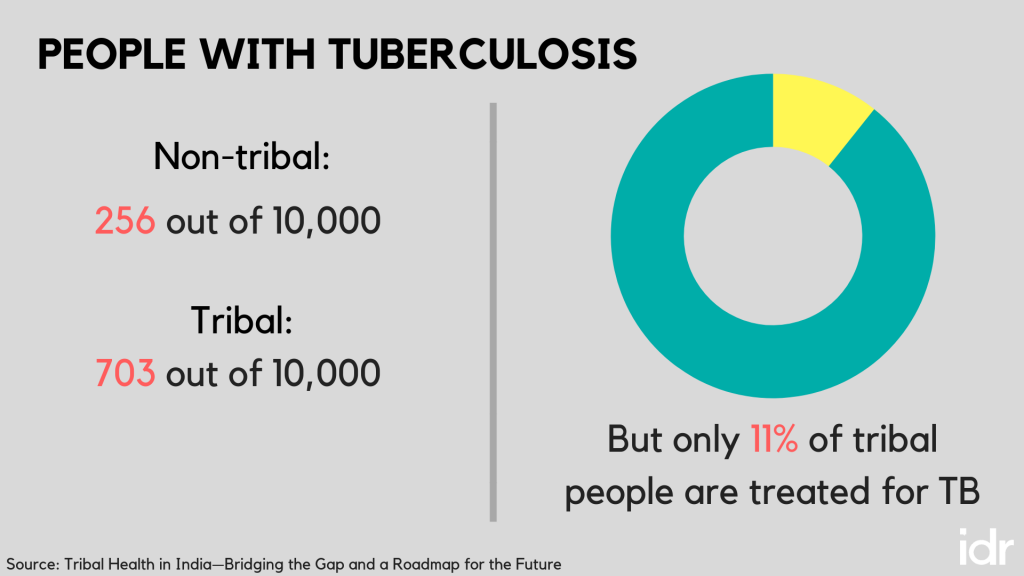

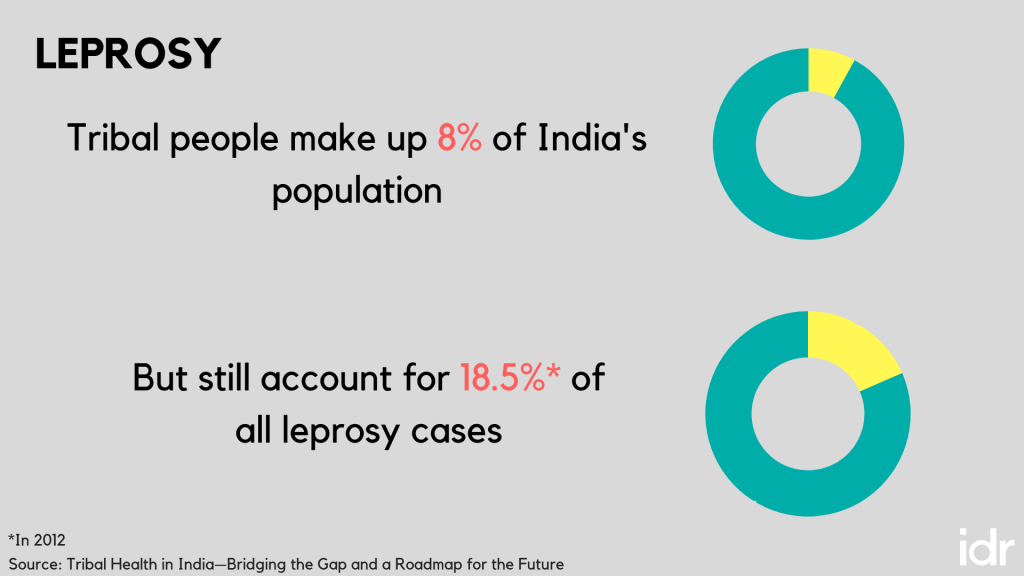

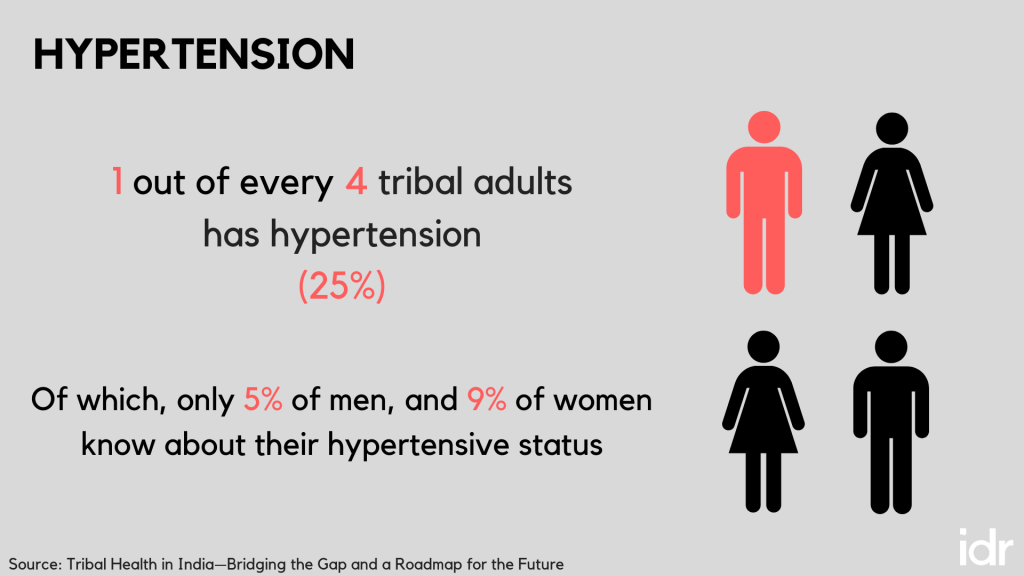

Tribal communities face the ‘triple burden’ of disease. Apart from high rates of malnutrition and communicable diseases (TB, leprosy, HIV etc), the advent of rapid urbanisation, and changing lifestyles and environment, has led to a rise in non-communicable diseases as well (cancer, diabetes, and hypertension). These are both in addition to the burden of mental illness and subsequent addiction.

Taking this into consideration, the committee made state visits to tribal areas, organised a national workshop, reviewed evidence from other countries, and looked to organisations working on ground with tribal communities to identify possible solutions, and chart a roadmap for the future.

What can be done to improve the state of tribal healthcare?

The report lays out nine recommendations for the future. The overarching goal, according to the committee, should be to bridge the gap in healthcare for tribal communities, and to bring health coverage and indicators at par with the state average by at least 2027.

To do so, a functioning, sustainable system of healthcare should be in place by 2022. Focus needs to be turned to comprehensive primary healthcare, local participation and human resources, and health education and research.

The committee emphasises the following:

- An annual budget equal to 2.5 percent GDP per capita basis must be allocated and spent on tribal healthcare (this comes to approximately INR 2500 per tribal in 2015-16).

- New entities—a Tribal Health Council and Directorate for Tribal Health—must be established at both state and union levels, to focus solely on tribal health including generating data, reviewing finances, and monitoring programmes.

- Service delivery needs to be restructured so that the government focuses 70 percent of its resources for tribal health on primary care, and makes the basket of healthcare services larger.

- All of the above must be matched with adequate human resources and infrastructure.

By ensuring that adequate attention and diligence is paid to tribal healthcare, and structural changes are implemented to incorporate tribal health needs, the state of tribal healthcare can improve.

Related article: Why does undernutrition persist in India’s tribal populations?

A significant gap highlighted in the report is the lack of healthcare professionals that are available to work with tribal communities. Healthcare professionals view postings in tribal areas as a ‘punishment’ of sorts, and are hesitant to go, much less stay, there.

With this in mind, the report emphasises the need for a significant mindset change, but more importantly, points to the opportunity that lies in motivating and training tribal people themselves to join the health force. “If we work with the communities, we will find that tribal youth are an excellent resource, and inducting them into healthcare will be a more feasible, sustainable, long-term solution.”

The report also states that traditional healers within tribal communities should be recognised and utilised. There is no dearth of health-related folklore in tribal communities, and tribal people rely heavily on naturopathy, using medicinal leaves, roots, fruits, and seeds from their surrounding ecosystems. The lack of spirituality and emotionality in the modern healthcare system is a factor that sometimes keeps people away from public health systems; including traditional healers in healthcare programmes could begin to address this issue.

It is important to look at tribal health problems as separate and distinct, and clubbing them together with the issues faced in general by rural populations negates the vastly different context within which tribal communities exist.

The committee identified 10 health issues that affect tribal people disproportionately. These are: Malaria, malnutrition, child mortality, maternal health problems, family planning and infertility, addiction and mental health issues, sickle cell disease, animal bites and accidents, low health literacy, and poor health of tribal children in Ashramsalas.

These problems are specific to tribal communities, should be recognised as such, and then be addressed with the community in mind.

As mentioned earlier, there is a dearth of data available on tribal health indicators, and so moving forward, the committee outlines four principals that must underpin all research.

- Respect for tribal culture,

- Relevance to tribal communities,

- Reciprocity through a two-way exchange of learning, and

- Responsibility to ensure that the research being done has no adverse effects on the communities.

The report is a resource and guide for anyone interested in tribal health, rights, and policy making. The recommendations for improving the state of tribal health provide an in-depth understanding of the systemic changes, as well as the mindset changes required for tribal healthcare to advance.

You can now access the full report, executive summary, and policy brief at http://tribalhealthreport.in/.

This article was revised on November 15, 2018 to address certain factual inaccuracies in the earlier version.