Two large challenges facing the country today revolve around addressing the ‘skills deficit’ among our youth and improving learning levels of students in our government schooling system. The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER)—a survey that provides estimates of children’s enrolment and basic learning levels for each district and state in India—acts as a guide for policy makers, donors and institutions to focus on continuous improvement.

ASER’s recent ‘Beyond Basics’ report looks at the ‘in between’ ages of 14 to 18 years when mandatory education ends (14 years) under the RTE Act and where adulthood (18 years) begins. The report makes one broad statement: ‘Although many children continue to secondary school, ASER data shows that their foundational reading and math abilities are poor.’

The RTE Act has been quite effective in improving three critical metrics: higher enrolment, lower dropout and completion of mandatory basic education. However, given that much of India’s youth will graduate as a result of this Act, it is imperative to think beyond these basics.

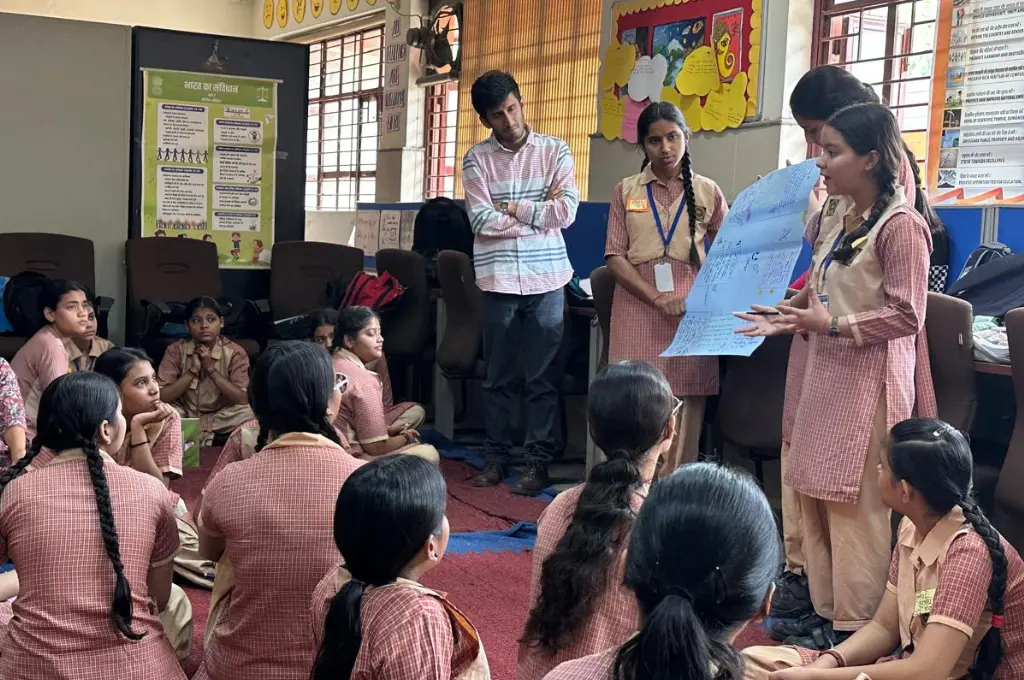

For children to reach their full potential, many inter-linked systems have to work well at different phases. The role of the government has become more critical than before, especially in coordinating efforts across various departments such as child welfare, primary and secondary education, skill development and so on. No less important is working at various levels of schooling, as well as working with parents, students, teachers, communities and institutions.

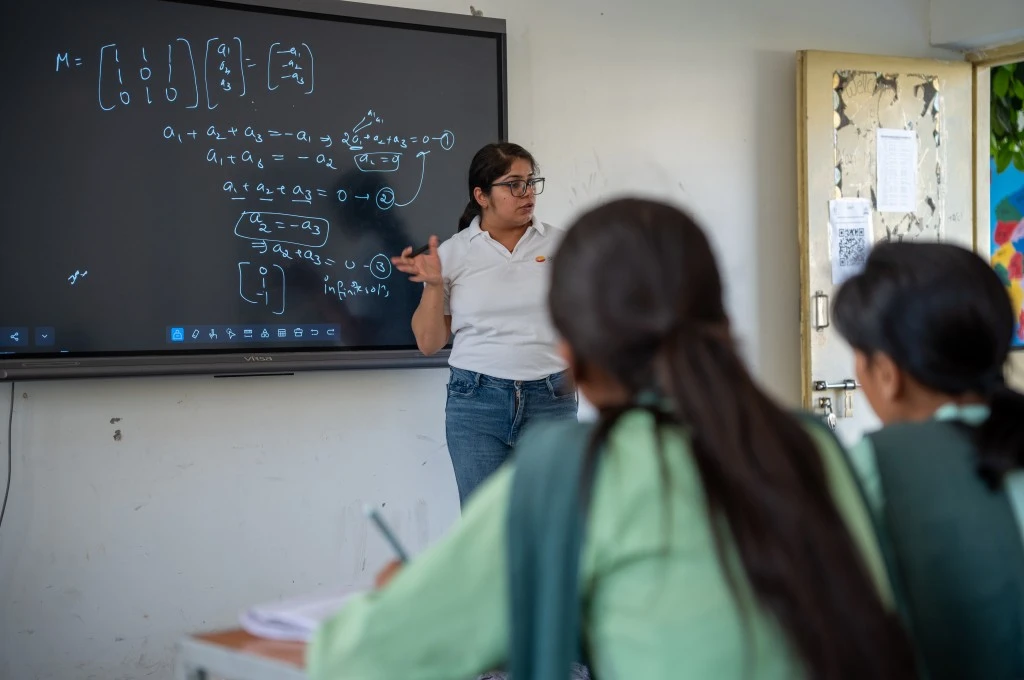

We need to reimagine how our learning systems are designed and delivered, so our children are equipped to reach their full potential – rather than becoming ‘bricks for a wall’.

But education alone is not a proxy for employability

While multiple initiatives focus on improving learning levels among students, there is also a parallel conversation emerging around the skills of the future. A lot of new literature, both from academia and think tanks, prophesises the need for a new layer of skills and behaviours that are required to navigate the future.

Traditional as well as emerging gig economy enterprises recognise the need for these new skills and are relooking at the long-held idea of education as a proxy for employability. With employability data on the average Indian youth showing no significant improvement and given the sub-optimal learning levels of most school-going children, it has become even more imperative to provide enabling life skills within the education and learning process at the school level.

These skills go beyond just academic and functional literacy and point to more fundamental non-cognitive and cognitive traits that children develop before adulthood. Result-orientation, problem-solving, inter-personal skills, and the ability to learn from and thrive on feedback are some of the skills that employers seek in entry-level applicants seeking employment.

The workforce of tomorrow requires knowledge and functional skills; as technology advances and automation increases, the low skill aspects of jobs are likely to reduce. One study estimates that while only 5 percent of occupations can be fully automated with currently demonstrated technology, 60 percent of occupations have at least 30 percent activities that can be automated. Not surprisingly, it is lower skill activities like physical work in predictable environments that are most susceptible to automation.

Today, for instance, an on-demand driver listed on an aggregator platform needs not only driving skills but also spatial and communication skills and the ability to use digital devices to negotiate the market. What might this look like tomorrow?

The future of workplace, future of work, the skills needed to be relevant and the conventional idea of security associated with jobs—everything is changing quite rapidly across sectors. Thus, it may be appropriate to reimagine the way learning systems are designed and delivered; the focus must be on building skill sets that allow children to negotiate the future and stay relevant in it.

A holistic way to look at employability

Today, India is dancing along the edge of a demographic dividend. We need to act now so we can make the most of the surge in our working-age population (currently 630 million-strong). A crucial step in this direction involves maximising the productivity and potential of the workforce. The next stage of India’s growth requires a level of human capital that is healthier, better educated and more productive.

Several empirical studies highlight how impaired cognitive ability is linked to poor health and malnutrition in early childhood. This has a large and irreversible impact on the individual’s capacity to learn and earn later in life.

In studies conducted with Indian children aged 5-7 years and 8-10 years, stunting is shown to have affected the development of higher cognitive processes such as tests of attention, working memory, learning and memory, and visuospatial ability. A sample of adequately nourished kids performed as much as two to three times better than malnourished children on many aspects of cognitive ability.

If we are to go by ASER, not only is there a need to focus on cognitive development as it relates to education, but we must also factor in the links between early childhood nutrition, education and employability when designing programmes.

The abilities and talent relevant for the future are very much tied to how our nation addresses the development of our children in a holistic manner. Where capabilities and abilities are shaped by learning systems, environment and life experiences, the likelihood of somebody’s true potential and talent never surfacing is quite real. And that’s the knowledge that must inform how we approach design of programmes in education and skill development.