In the 1980s and 90s, much of the development work in India was shepherded by leaders who had come from the JP movement–a people’s movement protesting widespread government corruption. These leaders inspired many others to join the grassroots movement for change.

This spirit of volunteerism changed with the migration of professionals, who introduced systems and processes in social sector organisations. Gradually, two approaches emerged—one based on civil and political rights, and the other on service delivery.

At Hivos, the humanist funding institution where I worked, we could see the tension between these approaches across our programmes, which were a mix of being rights-based and service delivery-focused. We realised that to bring about large-scale change and solve complex development problems, people with different perspectives needed to come together.

Coalitions – The sum of parts

Each coalition has a distinct character, defined by its overarching purpose, the organisations and individuals it brings together, its leadership and structure, intended lifetime, and its outcomes. There are also unintended outcomes—on its constituents and the sector at-large—which result from what the individual actors bring to and take from the coalitions.

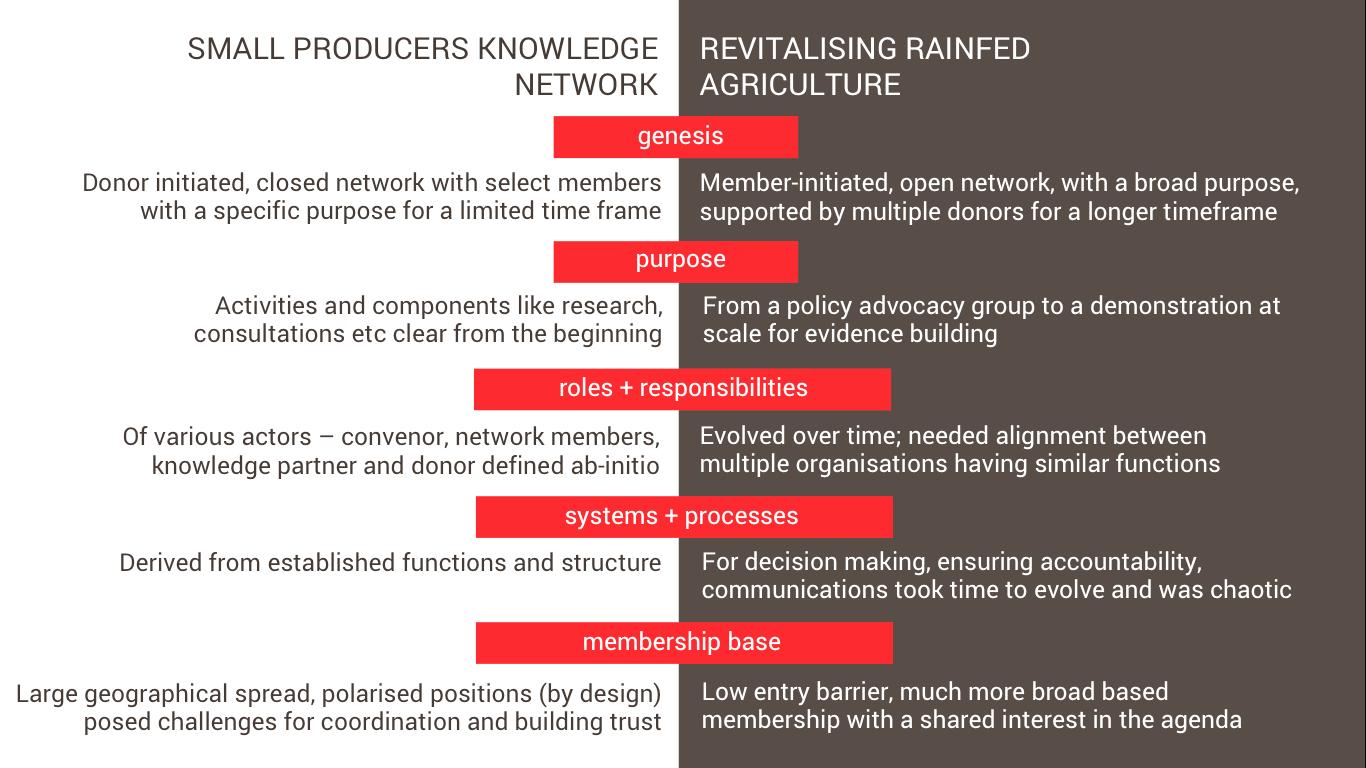

I’ve had the opportunity to participate in a number of such initiatives, two of which I will use as examples to illustrate the lessons I have learned, about what it really takes to work together.

Photo Courtesy: Hiveminer.com

1. Knowledge Network (KN) on Small Producer Agency in Globalised Markets

The knowledge network on Small Producers Agency in Globalised Markets (SPAGM) was one of the many knowledge programmes that Hivos initiated, which sought to examine if knowledge, as opposed to funding projects alone, could bring about change. We aimed to question whether it was equally important to examine external factors that could indirectly impact outcomes.

[quote]Like-minded organisations are useful for amplification and efficiency but un-like minded people are more useful for generating new knowledge.[/quote] The KN’s constituents included practitioners, academics, policy makers, industry and representatives of farmers organisations–between 15-20 individuals from across Latin America, Asia and Africa. The network was only meant to last for three years with the sole purpose of producing knowledge for influencing change, difficult though it was to envisage all the contours of that change.

2. Reviving Rainfed Agriculture Network (RRAN)

The evolution of RRAN on the other hand was much more organic—initially, it came together as a group of civil society organisations working on various aspects of rainfed agriculture. Hivos and Ford Foundation jointly supported the group.

Our assumption was that there were organisations across the country who had demonstrated expertise in the use of appropriate technologies for production including in seeds, soil fertility, water, cropping systems and so on. However, these technologies had neither been demonstrated at scale, nor had all aspects necessary for sustaining agriculture been demonstrated in one common area.

RRAN’s purpose therefore was to articulate and if possible demonstrate, a paradigm alternative to that of the Green Revolution, and postulate the nature, amount and delivery of public investments, specifically for rainfed agriculture.

Source: Bishwadeep Ghose

Lessons from the experience of large scale coalition building

1. Design: think about what brings and keeps people together

There must be a larger, shared purpose

Any collective effort that comes together organically, like RRAN, has a much larger chance of sustaining, versus something stitched together by a third party. Each organisation needs to believe that what it cannot achieve individually will be possible through that collective.

But to keep people engaged, especially in the absence of any formal obligation to participate, it is important to have early milestones that demonstrate the strength of the collective.

Design for and celebrate quick wins early on

This is important because members are voluntarily giving time. Unless they see the value, membership will erode over time. Hence, no matter how small, collective gains—as opposed to individual gains—are important to plan and share.

2. Leverage collective influence and credibility for policy advocacy

With the KN, the credibility of the individual members made the sum of parts greater than the whole. Members thus leveraged the strength of the coalition in different ways.

When we held meetings in a host country, we were taken seriously because we represented a diverse set of actors across diverse countries. For instance,one of our members from an Indonesian university, was able to use the heft of the coalition to introduce curriculum on smallholder farmers into the university system. Another Guatemalan member, who represented agribusiness as well as the political class, could effectively use the KN’s research to introduce a policy to support agri value chains in the country.

We must recognise the role of funding in impacting the dynamics between coalition members, and design accordingly.

In India, the coalition presented its research, Changing mindsets: small-scale farmers in the globalised market to the minister of state for agriculture and the small farmers agriculture consortium, where some of the insights caught the attention of the policy makers. None of these were part of the formal design of the KN. These interactions in turn influenced the thinking of individual members as well.

3. You need the right balance of structure, systems and processes

Having a trusted, lead organisation is key

With coalitions, having a lead organisation that is acceptable to all members is fundamental to success. This decision need not be donor-led; in fact, it is better if the members decide. It’s important to select an organisation that everybody respects and views as a thought leader, because enduring trust is critical for sustaining any form for collaboration.

The KN was set up by a donor, but the convening and agenda setting power remained with members. It took time for the members to get to know each other within and across regions for communication not to be mediated by the donor.

In the case of RRAN, the day-to-day decision-making was carried out by a group of self-appointed members called the ‘core group.’ The lead partner, also belonging to the core group, served as a thought leader for the network as well as a facilitator for the funds.

Being inclusive and democratic is great; until it’s not

With RRAN, both Ford and Hivos were clear right from the start that we did not want the network to be donor-driven. The members would decide the charter, take funding decisions and design their own systems of accountability. Both funders would go by the recommendations of a core decision-making body. This was an advantage and a drawback at the same time.

Initially, since there were few systems in place, the network grew organically. Entry barriers were low and very soon the Googlegroup—the forum for communicating and sharing information—had more than 300 members. Continuous communication, which is critical for any network, was possible through weekly skype meetings.

However, because RRAN had few defined boundaries, the group’s management became unwieldy with time.

4. Structure and process – how much is too much?

As any coalition or network grows the governance and the management face some challenges. The need to balance informal processes with formal systems; democratic functioning with accountability; flexibility with purposefulness and the usual functions of holding the network together—coordination, communication and transparency.

RRAN went through three sets of internal decision-making structures over time—the core group, the strategic leadership group and the executive committee (often with the same members). The board, which comprised eminent people changed twice, and we even had two secretariats over a period of five years!

We needed an elegant structure that would serve the purpose without becoming overbearing for the constituents. A heavy structure can take away from the network’s identity and increase its dependency on funds. And the engagement between the core group and the voluntary part of the network can weaken.

5. Think about sustainability from the beginning

When a coalition has a defined set of objectives for a specific period of time, issues of sustainability come into play because funding creates a dependency. The only way to counter this is have the discussion earlier on so that the network can prepare itself.

When the funding gets discontinued, it’s equally critical to ask whether there is a need for the political part of your coalition to continue. With the KN, the formal coalition more or less concluded with the funding, while the relationships established during the course of the programme continued informally much beyond the funding period. RRAN continues as a network even today, in part because funding always played a small role in the overall agenda. And members continue to see the value in being a part of a larger network.

Photo Courtesy: Renuka Motihar

The questions worth asking

With large scale collaborations, there can be no template; there are too many variables involved. There are only principles that we can share from our own experiences. Even still, questions remain:

- Can there be the mechanisms for sustaining the energy of a network?

- Can a network function as an organisation, without it taking the shape of a legal entity?

- What should the role of a donor be in such coalition efforts? Can a donor deal with unpredictability–of outcomes and timelines?

- If the coalition is dependent on that funding for success, is that a good enough reason to continue?

- How does a network manage diversity–of opinions, perspectives and way of doing things, if that is what it seeks to do in the first place?

- How does one resolve the dichotomies between the functions of a secretariat and its role as a thought leader?

- How do we account for the unintended outcomes that materialise from such collectives? What should be the indicators of success or failure for networks?

We may never have a one-size-fits-all answer, but lessons and reflections may help others chart newer coalitions that achieve what individual organisations may never be able to.