Rohit is a 17-year-old living in Pune. He has autism.

His parents have struggled to find a vocational or higher learning programme for him, so he travels eight hours every day on a bus to Mumbai and back, just to attend a catering course.

Rohit’s situation is indicative of the key challenges in India’s effort to educate all children. Like him, children with disabilities (CWD) face a number of barriers that prevent them from obtaining a quality education.

Identifying disability is a challenge; poverty and under-resourced environments exacerbate the situation

Atma, the organisation where we work, carried out a survey interviewing 21 organisations—segregated school setups, vocational training institutes, therapy centres and community rehabilitation centres—working with children with disabilities. Fifty percent of the leaders of middle- and high-income schools reported that parents of CWD had knowledge of the disability before enrollment.¹

In the case of low-income schools, 60 percent of the leaders stated that parents of CWD did not have any prior knowledge about their child’s disability. These findings are important because they reveal gaps that disproportionately disadvantage the poor, especially families with children that have disabilities.

While middle- and high-income families have a variety of channels through which they can access information about primary healthcare, low-income households—rural and urban alike—tend to rely on health and medical camps, the frequency and quality of which vary widely.

This knowledge deficiency among the poorer parents makes them largely dependent on the school’s administration and faculty when it comes to their child’s development. In some cases, schools may not be adequately resourced to take on that responsibility entirely. In the case of wealthier households, parents can exercise more control over their child’s education and the onus of care doesn’t, therefore, fall completely on the school.

Thus, in a developing country like India, low identification numbers are particularly concerning as disabilities are often exacerbated in under-resourced environments. The more the delay in identification, the greater is the chance of an exacerbated disability, and higher is the cost to quality of life.

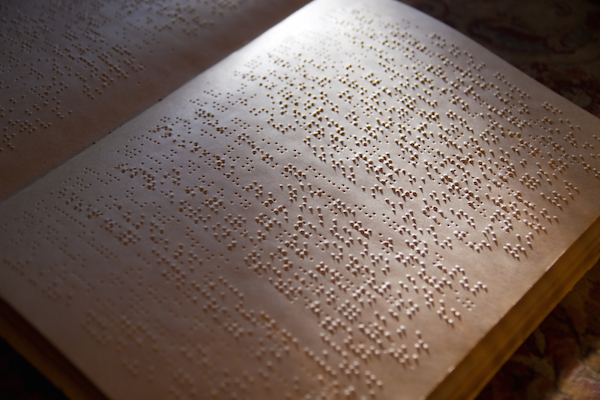

When dealing with children with disabilities, both pedagogy and clinical intervention must cater to the specific needs to each child as much as possible| Photo courtesy: Atma

Disability is under-reported, which gets reflected in the number and quality of resources devoted to it

Disability is often wrongly considered to be an issue that affects a few. The 2011 Indian census pegged the figure at roughly 2 percent of the nation’s population. But since WHO estimates that 15.6 percent of the world’s population is disabled, India’s figure seems disproportionately low. We do, after all, make up one-sixth of the world’s population.

This underestimation creates two challenges. One, in spite of progressive legislation including the Right to Education (RTE) Act and the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (RPWD) Act (2009), the availability of existing education services fails to meet the demand.

The RTE Act mandates inclusion of all children in mainstream schools. This has hopefully provided some access to critical resources for CWD, but knowing how the mainstream schooling falls short even for non-disabled students poses the question, “Are schools currently capable of supporting the inclusion of children with disabilities?”

As with mainstream education, government regulation has focused more on resource allocation and physical infrastructure, rather than provision of quality services.

Two, quality services within inclusive education remain unreachable for most CWD. When dealing with children with disabilities, both pedagogy and clinical intervention must cater to the specific needs to each child as much as possible. This high intensity of service provision means that recruiting and retaining qualified staff is both extremely important and difficult to achieve. Staffing challenges were reported as the most crucial organisational pain point by 14 of 21 schools surveyed. Our research also showed that due to the lack of qualified teaching staff, student-teacher ratios in segregated schools are often stretched to as much as 8:1.

Moreover, funding challenges and high asking salaries from qualified candidates in special education force smaller segregated setups to heavily rely on in-service training of under-qualified candidates.

Because of these challenges around the availability and quality of inclusive education within schools, segregated setups continue to proliferate and are a popular choice for parents. We have found that there is a need to support these setups to begin their move towards inclusion within mainstream schools. Inclusion, while not simple, will go a long way in enhancing the scope of a student’s achievement once out of school.

State support is lacking and benefits are difficult to avail

The official yardstick to determine the type and extent of a person’s disability and the concessions they are entitled to comes in the form of a disability certificate, which acts as ‘proof of disability’ and was codified through the 1995 PWD Act.

Obtaining this document, however, is a laborious process and therefore limits the tool’s ability to empower individuals with disabilities. On what basis it is granted and after what time period is often arbitrary. Parents from low-income households are unclear about the benefits/ concessions relating to exams, travel and tax that CWD can avail with the certification, and therefore, in weighing the costs of obtaining such a certificate, often decide against it. This, in turn, impacts government reporting on national disability figures, as this document is the primary source of data used.

The mindset is still one of segregation, rather than inclusion

Sadly, the pervading perspective is that disability is something to be diagnosed and cured.

A more enabling way to think about this instead would be how an individual with a disability can participate successfully within their environment. For example, for students with physical disabilities, classes can be moved to the ground floor to make them more accessible.

What does all this mean and what needs to be done?

Children with disabilities are not considered in broader education discussions. Funders committed to improving education need to be thinking about how children living with disabilities are being integrated and included in the programmes they support.

In order to achieve this, investing in the following areas will be catalytic in improving access to education for all:

- Programmes that work in communities:

- To equip parents to identify disabilities in their children, and

- To help enrol children early on in intervention programmes.

The nonprofit Gharkul, for example, ensures early identification in the community through its ECD programme, and thereby ensures higher enrollment in their following school programme.

- Programmes that work with mainstream schools:

- To develop resources that support schools to create an inclusive culture. Public-private partnerships have performed well in this space.

Mimaansa, a Mumbai- based nonprofit, works with 11 BMC schools to do this, working with nearly 4,500 students.

- To develop resources that support schools to create an inclusive culture. Public-private partnerships have performed well in this space.

- Assessments that acknowledge pre-academic skills, for instance, ensuring a child can match, identify and demonstrate through non-verbal behaviour rather than verbal learning of the alphabet.

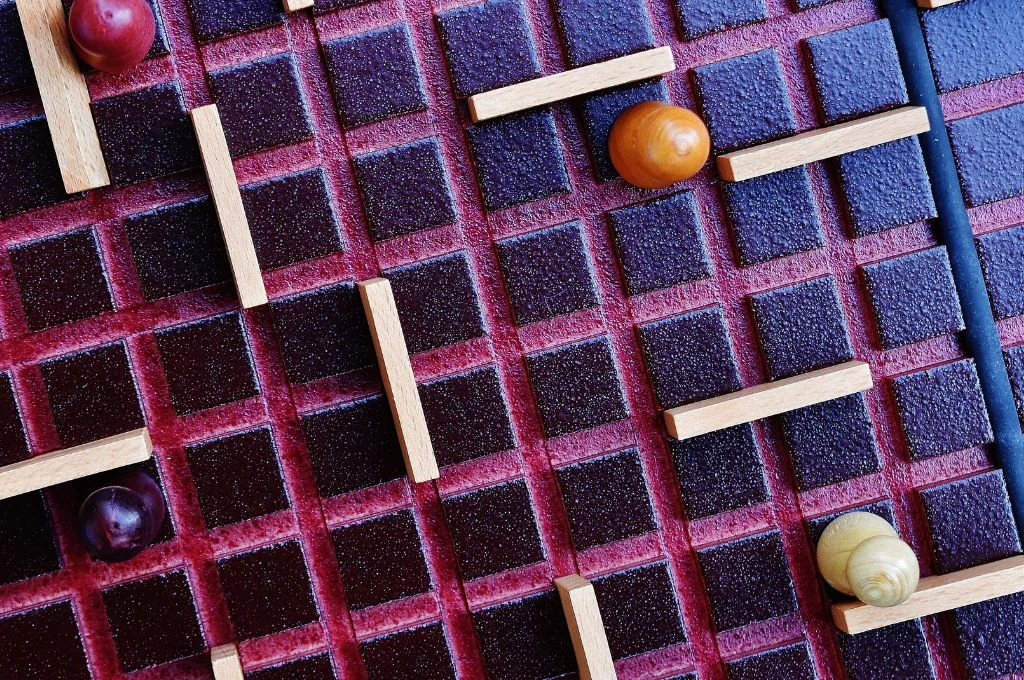

- Inclusive materials for classroom instruction that serve CWD. Sol’s ARC develops curriculum and implements it across both segregated setups and mainstream schools to bridge the gap between them.

In India today, children with disabilities are excluded. Accepting poor quality means that we are continuing to expect less from these exceptional young people.

—

Footnotes

- The other 50 percent neither agreed nor disagreed with parents having prior knowledge on this subject.

Dr. Franzina Coutinho and Satvika Khera provided edit support at Atma for this article. Atma published its report on ‘Bridging the Gap: Towards Inclusion in Education’ on the International Day of Persons with Disabilities, this December. The findings present the landscape of disability management and access to supportive resources, in both the public and private education in Mumbai. Read the full report here.