We are in the middle of a pandemic, one that is moving relentlessly and bringing us collectively to our knees. We have already been dealing with another pandemic; one which is not talked about much—violence against women and girls, which has a strike rate of 1 in 3 women. How do these two pandemics relate to each other?

A friend tells me she participated in a call to understand how organisations such as SEWA and Ekjut are working to help women in the informal economy—beedi workers, fisherwomen, and others—manage in these times. Friends and colleagues are swinging into action to raise money for daily wage earners and others who are impacted by COVID-19. We need all these efforts. But experience and research show that in an epidemic or a calamity, a gender analysis of both the preparedness and the response to the calamity improves both gender and health equity.

Related article: Are economic systems sexist?

Health emergencies are not gender-neutral

During the 2014–16 West African outbreak of the Ebola virus, it was established that women were more likely to be infected by the virus, as they played prominent roles as caregivers within their families, and as frontline healthcare workers. Women were also affected when resources for reproductive and sexual health were diverted to the emergency response. This contributed to a rise in maternal mortality in a region which had one of the highest rates in the world. During the Zika virus outbreak, differences in power between men and women meant that women did not have autonomy over their sexual and reproductive lives. This was aggravated by their lack of—or inadequate access to—healthcare and financial resources to travel to hospitals for check-ups.

It looks like we are facing a similar scenario again. While there is no data yet that tells us whether COVID-19 affects more women or men, 67 percent of health workers worldwide are women. They are, and will be, at the forefront of this battle. Many among them will be part-time workers—more women than men. They will be the first to be laid off or given shorter contracts during and after the crisis.

Within families, there will be disparities. As couples work from home, who is looking after the children, since schools, nurseries, and after-school hobby centres are closed? When family members are sick, and/or in isolation, who is more likely to play the role of caregiver? My guess is: more women than men.

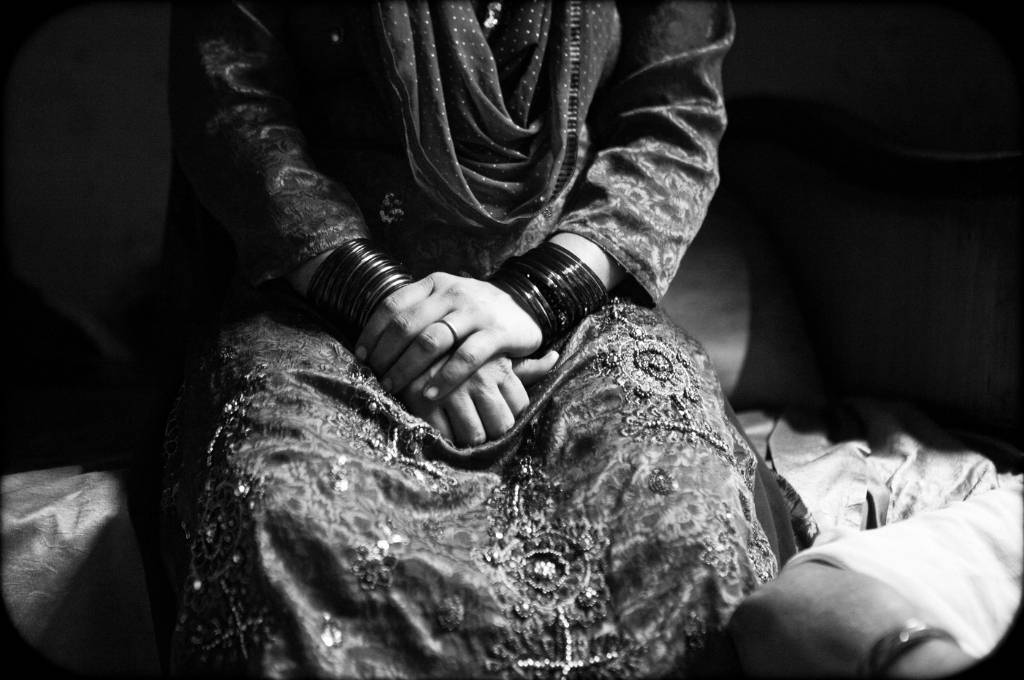

Women will be the first ones to lose their livelihoods, both in the immediate period and then for as long as it takes for the economy to return to normalcy. | Photo courtesy: Pixabay

The impact of COVID-19 on women and girls

Millions of women—in India and elsewhere–are employed in informal and unskilled jobs with low wages. Women in the unorganised sector are often the most marginalised—working as daily labour or with contracts that provide no security. They are women of colour, immigrants, belong to lower castes and minorities: beedi workers in India, farm workers in the US, domestic workers worldwide, fisherwomen, and sex workers. How are they going to be affected? They will be the first ones to lose their livelihoods, both in the immediate period, and then for as long as it takes for the economy to return to normalcy. Research also shows that due to traditional gender roles, it takes women longer to go back to work after a disaster.

Related article: Women bear the burden of India’s water crisis

Girls aged 14-18 are already vulnerable: in India 39.4 percent are out of school. School closures will affect their lives and we need to think about how many of these girls will return to school, once this crisis dies down and normal life resumes. When families are hit with an economic crisis, nutritional needs of the women and girls in the family are neglected.

Isolation can increase the risk of domestic violence

And, what about issues of domestic violence during these times of financial and emotional stress? Isolation can be particularly dangerous for those in abusive relationships. The French feminist collective NousToutes recently highlighted the potential risk of domestic violence cases rising as a result of enforced isolation, and called upon people to make use of the emergency hotlines in France. A tweet from them read, “Being confined at home with a violent man is dangerous. It is not recommended to go out. It is not forbidden to flee. Need help? Call 3919.” A statement released by the National Domestic Abuse Hotline in the US noted that with companies encouraging their employees to work from home, domestic violence abusers may take advantage of an already stressful situation. Globally, in countries including China, Greece, and Brazil, there are reports of increasing numbers of cases of abuse and domestic violence that can be attributed to coronavirus isolation.

Closer home, violence against women is normalised to such an extent that it might not even strike anyone as a problem. Organisations that run hotlines and provide services to those affected by domestic violence in India tell us that there’s absolutely no data to show whether there has been a spike in instances of abuse since the lockdown was announced. They do however have anecdotal evidence of people reaching out for help. In some countries, governments have declared helplines as essential services and they have been instructed to remain open. In India, we have not seen any such response yet.

Economic and financial strain is linked to increased risk for violence against women

And yet, we know that economic and financial strain—as this pandemic and the ongoing lockdown will inevitably cause—is linked to increased risk for violence against women. In India, in the very short-term, can we ask neighbours to be aware of domestic violence issues, be supportive bystanders, and interrupt violence through simple acts like ‘Ring the Bell’?

What can we do?

On average, women did three times the amount of unpaid care work at home as compared to men, even before the COVID-19 pandemic. Women will now be balancing one or more of the following: work, childcare, homeschooling, elder care, housework, and looking after any person who is sick in the family. We must encourage more equitable sharing of domestic tasks, so that women and girls can rest and aren’t overwhelmed. Can we also make sure that rations and other relief measures for women-headed households and single women reach them, and are not just token amounts? Can we ensure domestic workers get their wages, even if they are not coming to work because of the lockdown? These are a few simple measures that we can all surely follow at a time when women are again being deprioritised.

—

Know more

- Learn more about the knock-on effects the pandemic could have on women’s health, and why policy responses need to explicitly take into account its effect on women and girls.

- Read about why the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to be a disaster for feminism.

Do more

- Share this list of active helpline numbers for women facing domestic violence/intimate partner violence.

- Breakthrough is working with women’s organisations to create a gendered response to the pandemic. If you would like to get involved, write to contact@breakthrough.tv.