Blindness is a major public health issue, both in India and across the world. It is estimated that 1.1 billion people globally live with a vision impairment and that 90 percent of these are concentrated in low- and middle-income countries. For instance, India is home to more than 137 million people who have near vision loss and 79 million who suffer from impairment. According to the National Blindness & Visual Impairment Survey 2015-19, cataract (71 percent) and refractive error (13.4 percent) were the major causes of visual impairment among those above the age of 50 years. Cataract, a form of age-related vision loss, is responsible for nearly 51 percent of blindness globally, as per the World report on vision by the World Health Organization (WHO).

At least 771 million people across the world have vision loss that could be avoided.

While these numbers are huge and startling, it is also critical to note that 90 percent of vision loss is avoidable and at least 771 million people across the world have vision loss that could be avoided. According to a report by PricewaterhouseCoopers, an investment of USD 2.20 per person per year between 2011 and 2020 in low- and middle-income countries could have eliminated avoidable blindness. This is because presbyopia or near vision loss ie, the inability to see or focus on nearby objects, is experienced by many people around their mid-40s and this continues to advance with age. People with such a condition can easily correct their vision with a pair of spectacles or lenses and those who can afford the expenses, can opt for laser surgery or other refractive surgery procedures.

This may not appear as a major issue for those who can afford these services, but what about those who cannot? In our experience of working with low-income communities, people often hesitate to undergo even a basic eye-screening, as they worry about the expenses involved in the screening process and the treatment thereafter.

Connecting the dots

Poverty and blindness are believed to be intimately linked, with poverty predisposing people to blindness. People from low-income backgrounds are more likely to become blind due to the lack of access to and ability to pay for services. Blindness also exacerbates poverty by limiting employment opportunities, or by incurring treatment cost. Thus, poverty is both a cause and effect of visual and other disabilities that increase social divisions. Eradicating avoidable blindness enhances productivity, and thus impacts the many millions who are stuck in the vicious cycle of poverty and poverty-induced disability. According to a study conducted by Aravind Eye Care System in the Madurai region of Tamil Nadu, 85 percent of men and 58 percent of women who had lost their jobs as a result of blindness regained them following a cataract surgery. The study also found that an individual who regained functional vision through cataract surgery generated 1,500 percent of the cost of surgery in increased economic productivity during the first year post the surgery. This evidence demonstrates that eradicating blindness and restoration of sight not only reduces poverty, but also enables a better quality of life for communities and positively impacts the GDP of nations.

Impact on mental health

Apart from the links to poverty, poor vision can also have negative psychosocial consequences and cause disruption in people’s daily lives. According to the WHO, adults with vision impairment often have lower rates of workforce participation and productivity and higher rates of depression and anxiety than the general population.

With the dearth of information on mental health issues among the visually impaired in India, Mission for Vision (MFV) undertook a research study to understand the linkage between vision issues and mental health aspects such as depression and anxiety. The study population comprised of 813 adults with cataract, who were undergoing their first eye surgery. The findings showed that the prevalence of depression amongst adults with cataract was at 87.4 percent and the prevalence of generalised anxiety amongst adults with cataract was at 57.1 percent. This is significantly higher than the prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders in the general population without vision loss across Indian states, which stands at 3.3 percent each for both genders.

The research concluded that vision loss substantially impairs day-to-day routines and leads to deterioration of mental health. Visual impairment leads to loss of jobs and productivity and it also increases dependence on other family members. In particular, the women of the house often become caretakers of the person with visual impairment, thus limiting their potential and freedom to a large extent.

All of this combined with mental health issues for patients with visual impairment are far-reaching. MFV’s study also observed that adults with comorbid vision loss and depression are less likely to seek, be referred to, or use vision rehabilitation services; and those who do seek care tend to receive less service compared to those who are not depressed. This in turn pushes them further into the shackles of poverty, which affect their future generations and kin as well.

A gender perspective

Women often bear a disproportionate burden of health inequity across the globe and visual impairment is no different. Of the 253 million people in the world who are visually impaired, 55 percent are women (139 million). In terms of eye care, the gender disparity widens, as women do not get to access services with the same frequency as men. For instance, the cataract surgical coverage among women in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia is nearly always lower, sometimes nearly half of that in men. We need to prioritise the provision of gender-equitable eye care services to all vulnerable communities.

An optimistic vision

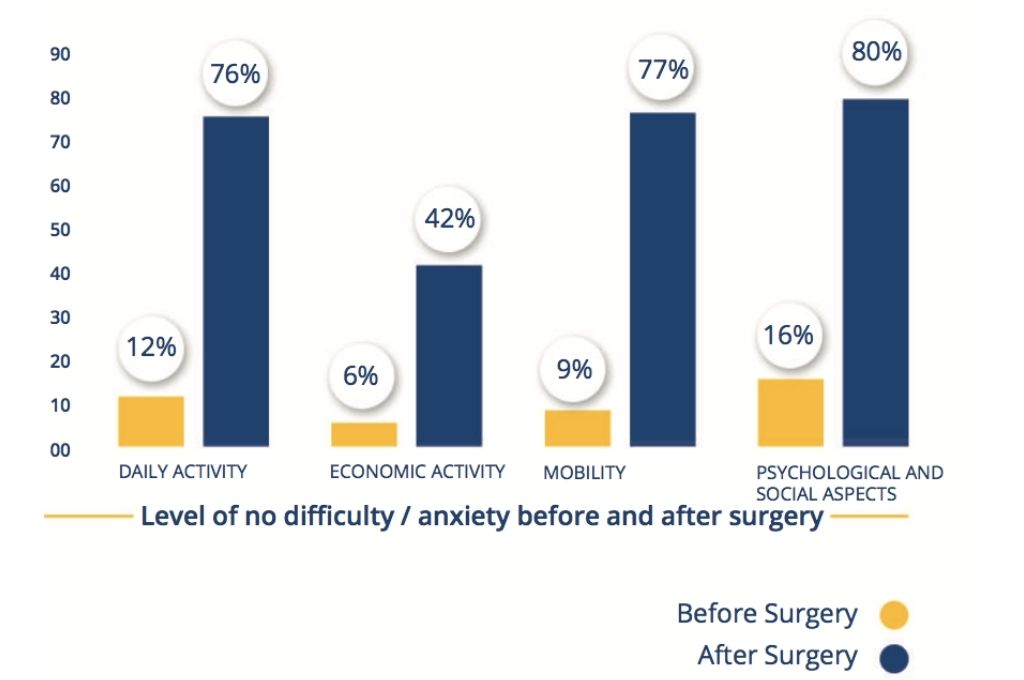

In an attempt to gather evidence on various dimensions of eye health systems such as visual acuity, quality of life, eye care practices, and barriers to accessing eye care, Mission for Vision has been using a technological innovation called PRISM (Patient Related Impact Studying Mechanism). This tool evaluates the impact of interventions by asking the patient 30 questions to determine change in quality of life and is administered twice: A few days before cataract surgery and six months after surgery.

Through this, we found that the provision of eye health services significantly impacts the quality of life of individuals. For instance, in the year 2019-2020, we assessed the impact of cataract surgeries on the quality of life of 2,677 patients across 22 states in India though questions exploring the difficulty or ease in daily activities, economic activities, mobility, psychological, and social aspects. The study found that 77 percent of patients reported improvement in mobility and 80 percent of them experienced improvement in terms of psychological and social aspects, thus implying improvements in productivity and mental health.

It is clear that the benefits of addressing avoidable blindness appropriately has enormous economic and mental health implications, not only for the people living with visual impairments, but also for those around them. Enhanced sight has been proven to improve health and well-being, promote workforce participation, and even advance educational attainment for school children.

Similar outcomes were observed in 2016-17, when PRISM recorded data of 17,000+ individuals across India before their cataract surgery. More than 8,000 were contacted after six months to assess the impact of the surgery on their lives. Before surgery, 44 percent of people engaged in livelihood activities mentioned challenges with their earning ability. However, the number decreased to 14 percent six months post the surgery. The visual outcomes after six months also matched with WHO recommendations of 90 percent patients attaining good visual acuity (can see 6/6-6/18) with the best correction. In the case of MFV partner hospitals, 91 percent of patients showed good visual acuity post-surgery.

Investing in preventing blindness

There is no doubt that investing in eye health has the potential to bring about transformative social change. A study commissioned by The Fred Hollows Foundation found that USD 4 of economic gain can be made for every USD 1 spent on eye healthcare in developing countries and that eye health stimulates the broader economy and brings life-changing benefits to individuals and their families. Without it, vision loss continues to cost the global economy an estimated USD 168 billion a year in lost productivity.

While there is no India-specific data on the funding gap for eye health, in the course of our work we have seen the gap continue to widen, with the recent pandemic adding other layers of challenges. In such a situation, philanthropists and foundations can play a critical role and make a meaningful impact. Investing in eye health will contribute largely towards the sustained growth and development of nations. The other important gains will be of accelerating social change and alleviating poverty through enhanced quality of life.

—

Know more

- Explore this resource on inclusive education for students with blindness and low-vision.

- Learn more about the findings of the National Blindness and Visual Impairment Survey 2015-19.