Development programmes are notorious for failure and unintended consequences. Why do we make some development mistakes over and over again? Often, we have enough evidence to know something does not work; yet, there is a substantial lag in learning.

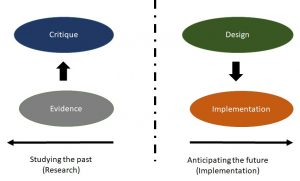

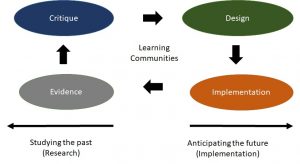

Drawing from my own experience in water resources research, I argue that this can be attributed to a communication gap between ‘thinkers’ and ‘doers’. Thinkers look at the past and sift through evidence, and doers look ahead to build, make, or implement. The persistent communication gap results in a failure to learn. One half of this problem stems from practitioners’ failure to make use of evaluations. But the other half has to do with what researchers produce, and how they engage with practitioners.

Often, we have enough evidence to know something does not work; yet, there is a substantial lag in learning.

When I was doing my PhD, one of my faculty advisers, a qualitative social scientist, told me in no uncertain terms that, “Dissertation research is not consulting. You cannot ask a prescriptive question; only a descriptive question as part of your dissertation research. You have to look back at something that has already happened and ask a what or why question. ‘How do we design a better policy or programme?’ is not a valid research question”.

This view, of course, is not universal. In engineering departments, designing a new product, tool, or technique is common. For instance, in civil engineering, building an optimisation model to advocate how dams should be operated is mainstream research. Indeed, the entire success of the Harvard Water Programme in the 1960s, at the peak of the dam-building era, was its claim that through computer simulation models, researchers could inform the design and operation of large multi-purpose reservoir projects to maximise ‘output’.

Likewise, economists have historically been comfortable with making policy recommendations. In fact, public policy departments in many universities are comprised primarily of economists. Perhaps it is precisely this comfort with making prescriptions that have allowed these disciplines to dominate public discourse. Both groups have done this by building quantitative models that can predict the outcomes of policies and programmes, allowing policymakers to justify choices based on ‘objective’ criteria.

These disciplines are able to be prescriptive by being narrowly concerned with ‘efficiency’ and being blind to politics, trade-offs, winners and losers, and equity concerns | Photo courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Social scientists, correctly, argue that this lopsided disciplinary dominance has been very problematic; these disciplines are able to be prescriptive by being narrowly concerned with ‘efficiency’ and being blind to politics, trade-offs, winners and losers, and equity concerns. For instance, maximisation of productivity of water (in cost per cubic metre) would require prioritising water first, to industry. But that would involve ignoring the lifeline needs of small and marginal farmers, who may need it for survival. To be fair, these critiques have indeed led to the broadening of approaches, at least outside India. Instead of being focused on just improving efficiency, globally, planners have begun to examine trade-offs to allow policymakers to engage in multi-criteria decision making (use of many different criteria with weights) or shared vision planning (allowing stakeholders to negotiate and arrive at a common vision or goals).

Quantitative models can only go so far, because they can offer insights on what to do, not how to go about it.

But this does not address the root of the problem. Quantitative models can only go so far, because they can offer insights on what to do, not how to go about it. Once it comes to the nitty-gritty of the implementation, the details are typically left to consultants. This is precisely where many programmes, which look great on paper, end up failing. One example is Tamil Nadu’s Groundwater Regulation Act, which was eventually repealed because it was ‘not workable‘. Another is the recent Jalyukt Shivar Abhiyan programme, which has been critiqued for ultimately not being able to address the drought, despite having been implemented in 16,522 villages in Maharashtra at a cost of more than INR 7,692 crores. In many cases, programmes are simply not implemented. A recent report by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) indicated that funds allocated for drinking water largely remained unutilised since 2012.

On one hand, silos between stakeholders create a culture where the people with the expertise on a particular social problem are often not the ones implementing solutions. There does not seem to be an easy way for the ‘softer sciences’, that actually study communities on the ground, to inform design of policy or practice. An ethnographer who has spent years studying the impacts of an infrastructure project or policy on vulnerable communities and is cognisant of the power disparities and corruption, would find it hard to ensure that future projects do not repeat the same mistakes. The consulting firms that design programmes and projects rarely reach out to them to ask how programmes could do better.

On the other hand, research cultures do not challenge researchers to be specific. Many studies highlight what not to do, without articulating what to do and how to incorporate lessons from past successes and failures to do better. Often, researchers remain content with making generic recommendations for more participation, inclusion, and transparency. Since few in the government know how to properly implement these ideals, it results in more critiques and problematising and the cycle continues.

Thus, the only form of engagement by many social scientists is to point out what’s not working, which deepens the rift between the thinkers and doers. Policymakers and practitioners end up being frustrated by research, which they believe will criticise, no matter what. In fact, it becomes easy to ignore the critiques altogether.

The two worlds stay forever disparate.

So what needs to change?

The first step is accepting failure, or at least imperfections, as an inevitable part of the development cycle and reducing the shame associated with making mistakes. As Rohini Nilekani pointed out in a recent article, “acceptance of failure is an essential part of innovation, which in turn is required for a successful outcome”.

Second, if we want to stop repeating the mistakes of the past, we need to create safe spaces to communicate in order to bridge disciplines, as well as the science-policy-practitioner divide. There are of course numerous conferences, workshops, and panel discussions where ideas and experiences can be exchanged. There are however, gaps: the events that researchers go to are not the same ones that practitioners attend, and the events are not designed to facilitate learning.

Third, we need to explicitly link the design phase to the learning phase through challenging researchers to articulate design principles. There are some examples in the emerging the field of implementation science in medical research, whose goal is “to promote the systematic uptake of research findings into routine practice”. In other words, what is needed is a specific set of actions (and associated funding for it) that will help us go from ‘what caused a programme to fail and another one to succeed’ to ‘how can we use the evidence to design a programme better’.

Learning may be harder for government, which is subject to political and bureaucratic constraints. But perhaps CSR funders, foundations, and private philanthropic donors could pave the way.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal.