Millions of students in India aspire to become doctors. But cracking one of the most competitive exams in the world does not assure them of a spot in a medical college. That is because private MBBS (Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery) seats, accounting for about 40 percent of the total seats, typically cost upwards of INR 50 lakh, putting them out of reach for the average Indian middle-class household.

Moreover, most financial institutions in the country do not provide such large loans. Even if they did, it would take 2-3 decades for students to repay them. The high cost of private medical education, coupled with the lack of student financing options, means that many meritorious students are not be able to ‘afford’ becoming doctors. Those who do pass through the private education system are likely to work in private hospitals in urban areas to recover their high costs. Thus, this problem has serious implications for the quality and accessibility of India’s healthcare system.

To recover the high cost of education sooner, graduates from private colleges mostly opt for lucrative private jobs in urban locations, resulting in an inequitable distribution of doctors. | Photo courtesy: ©Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Paul O’Driscoll

Becoming a doctor in India comes at a steep price

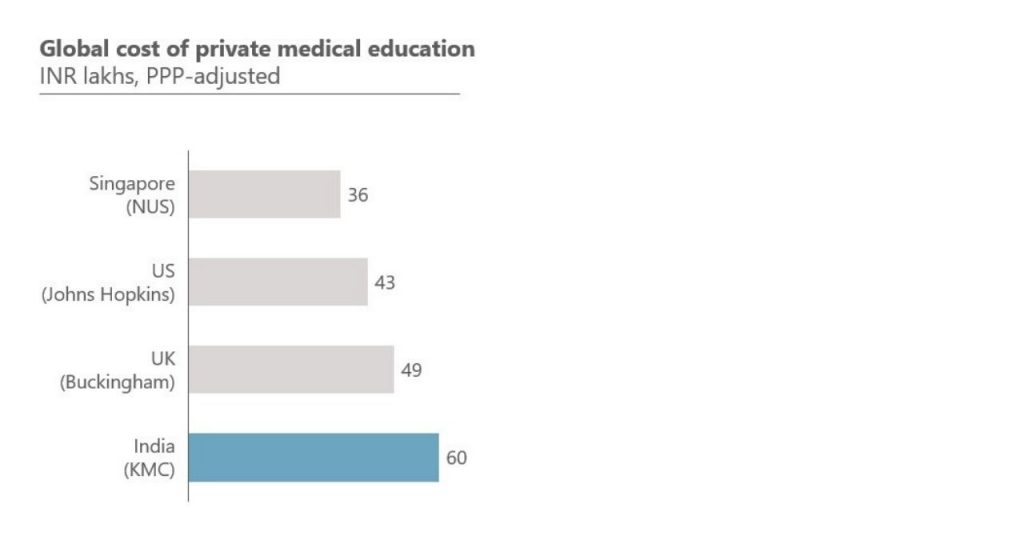

India has a highly privatised medical education system, with more than 250 private medical colleges enrolling 1.7 lakh students. At the undergraduate level (MBBS), these students typically pay INR 50-60 lakhs 1 (going up to INR 1.3 crore) 2 for a ‘general’ seat. 3

India’s private medical education system enrolls 40 percent of all students and is amongst the costliest in the world.

To put this into perspective, a similar course at the National University of Singapore (globally ranked #23) would cost INR 36 lakhs and at Johns Hopkins University (globally ranked #5) would cost INR 43 lakhs, after adjusting for purchasing power parity (PPP). Moreover, these fees are 5-10 times more than those charged by premium private institutes in other streams such as engineering, law, and management.

Source: Dalberg

Students who pursue postgraduate studies (specialisation or super-specialisation) at private colleges, would pay a total of INR 1-3 crores, 20-30 times more than what they would pay if they were educated in the government system. 4

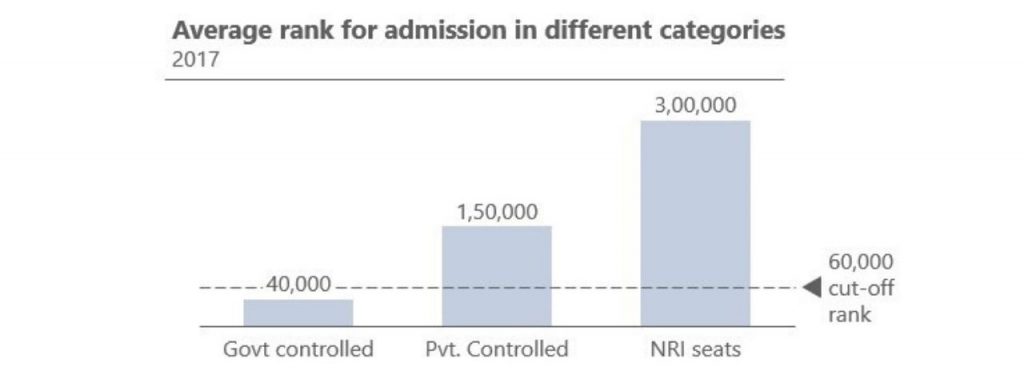

These exorbitant costs are driven, in large part, by regulatory mandates such as infrastructure requirements (it costs upwards of INR 200 crores to set up a private medical college) 5 and the huge demand-supply mismatch (about 15 lakh candidates apply for 60,000 MBBS seats). While the government plans to regulate fees for 50 percent of private college seats, as per the recently passed National Medical Commission (NMC) Act, student financing will be crucial for the remaining seats.

Student financing options are limited and unsuitable

Public sector banks, the traditional source of higher education loans in India, typically cap loan amounts at INR 10 lakhs, which are better suited to students entering streams such as engineering, law, and business, where fees are significantly lower. Even with private sector banks and non-banking finance companies (NBFCs), some of whom do not have lending limits, students face significant challenges, including high collateral requirements (usually 100 percent of the loan amount), higher interest rates, and short tenures (typically less than 15 years, for a domain where one starts earning adequately only after 10-15 years of joining an MBBS course).

Less than a fifth of qualified doctors are estimated to be working in rural areas.

As a result, the quality of students entering private medical colleges is lower than desired. Many candidates with top ranks in the national medical entrance test (NEET) opt out of the profession as they are unable or unwilling to pay the high private college fees. This is reflected in the fact that the average rank for government-controlled (low fees) seats in 2017 was about 40,000 and private-controlled (high fees) was about 150,000, well beyond the 60,000 merit-based cut-off. 6 7

Source: Dalberg

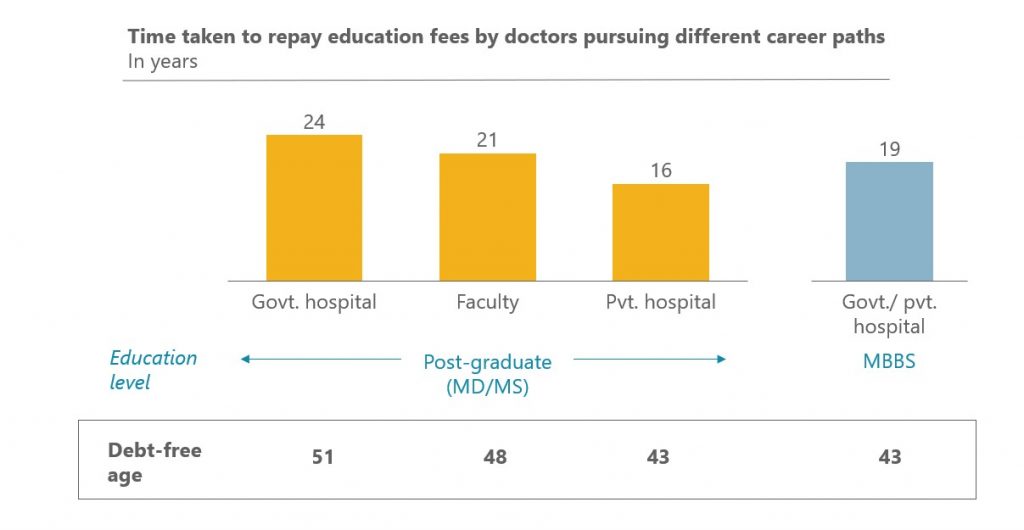

To recover the high cost of education sooner, graduates from private colleges mostly opt for lucrative private jobs in urban locations, resulting in an inequitable distribution of doctors. Based on average salaries and typical career progressions, both MBBS and specialist doctors (MDs) from private colleges are able to recover the cost of their education in their early forties if they work in private hospitals (mostly in urban areas), and almost a decade later (in the case of MDs) if they choose to work in the public system. 8 9 It is no surprise then, that less than a fifth of qualified doctors are estimated to be working in rural areas.

Source: Dalberg

Build solutions that make medical education affordable and equitable

In this context, there is an urgent need to develop tailored, innovative financing solutions to improve the quality of student intake and ensure a better geographical distribution of doctors. Below are some thought starters:

- Financial institutions can explore creating tailored products for medical education, characterised by higher ticket sizes, longer tenures and moratoriums, and reasonable interest rates. Medical school loans in the US, for example, frequently cover all expenses, have 20-year tenures, and do not charge interest while students are studying or beginning their careers. To make this possible, the Government of India could provide subsidies or guarantees to incentivise financial institutions to develop such products. “We can structure a loan with lower requirements initially and larger ones later (once students start earning), but would need government support in the form of guarantees, to reduce risk,” says an executive from a fintech startup that offers education loans.

- The government could develop conditional loans, wherein a portion of the loan is waived off, or the interest rate is reduced for students committing to serve in the public health system or rural areas for a specified time post their studies. Such a scheme has been implemented successfully by the Singapore government, which offers a 50-60 percent fee waiver to medical students that serve in the public health system for 5-6 years. Some states in India such as Odisha, Gujarat, and Maharashtra have also tested this model, and a national version could learn from their successes and mistakes.

- Finally, colleges, on their part, could proactively partner with financial institutions to make favorable loans and scholarships available to meritorious students. The Indian School of Business (ISB), a leading management institution, for example, has partnered with more than 20 banks and NBFCs to provide collateral-free loans that cover the entire course fees.

In summary, India’s private medical education system enrolls about 40 percent of all students and is amongst the costliest in the world, with students spending upwards of INR 25,000 crores every year in aggregate. 10 Many of our best and brightest students are being turned away from the profession due to the high sticker price of medical education and the lack of financing options. Those who do manage to finance their degrees are likely to opt for jobs in private healthcare in urban areas, depriving millions of ordinary citizens of good primary healthcare.

In this scenario, the development and adoption of innovative, tailored student financing models by the government and financial institutions can help address this issue.

- Based on a sample of 5-10 colleges

- Fees across colleges range from INR 25 lakhs to INR 1.3 crores for general seats and 2-3 times these amounts for NRI seats

- Private medical colleges usually have three types of seats: general/management seats (majority- 50-85 percent), NRI seats (~15 percent), and low-cost government seats (vary from 0-50 percent across states)

- Based on fees charged for MD/MS/DM/MCh degrees by a sample of 5-10 private colleges

- Based on interviews with medical college promoters, administrators, and a financial model developed by Dalberg

- Government controlled seats refer to seats for which the government controls the course fees. These include all seats in government colleges and certain reserved seats in private colleges (0-50 percent of total seats depending on state). Private controlled seats refer to seats for which private colleges decide course fees (these might be subject to fee caps in certain states)

- Even with low costs, the final ranks would not close at ~60,000 due to reservation of seats for non-general categories that require lower ranks and natural opting out of some candidates

- Payback periods refer to time after the completion of the course; 70 percent of course fees is assumed to have been borrowed at a conservative interest rate of 8 percent; salary progression is based on secondary data and interviews with doctors in India

- Other factors such as infrastructure, security, and lifestyles also drive the rural-urban divide, apart from purely salaries

- Total annual fees estimated by multiplying no. of students (~1.7 lakh) enrolled in private colleges (in MBBS + postgraduate courses) by the average annual course fees of INR ~15 lakhs

—

Know more

Learn more about the problems plaguing medical colleges and the underlying issues around setting up new institutes from this article by The Wire.

Understand the changes being brought about by the National Medical Commission Act, 2019, by reading this summary of the legislation.

Do more

- Connect with the authors Anubhav.Gupta@dalberg.com and Keshav.Kanoria@dalberg.com to learn more about their research findings.