‘Slum-free city’ is a term that is often used in India’s urban policy halls. It reflects both an important aspiration but also a crucial public obligation—of our urban local bodies, but also of state and central governments.

But what exactly does it mean to be slum-free? And by extension, if a city has to be slum-free, what happens to the slums themselves, when their living conditions improve? What are they called? Put another way, when does a slum stop being a slum? Surprisingly, there is no publicly stated policy on this key question. Nor is there enough data on the path out of slum-hood to neighbourhood.

Census 2011 provides a fair amount of information on India’s slums (some of this data has been challenged, but leaving this aside): the definition (minimum 60 households); the number of Indian cities that have slums (2,600) the number of slums across the country (33,500); the population in these slums(65.5 million): the infrastructure available (56% with access to water, 90% use electric power), and so on. But there is no information on slums that are no longer slums, those neighbourhoods that were slums in 2001 and graduated into… what?

This isn’t a trivial question. It forces us to define the desired end-state of a slum in very specific terms, so that slums can transition to this end-state, and people in the households there get access to the minimum quality of life that they deserve as citizens.

Related article: The gaps and opportunities in low-income housing

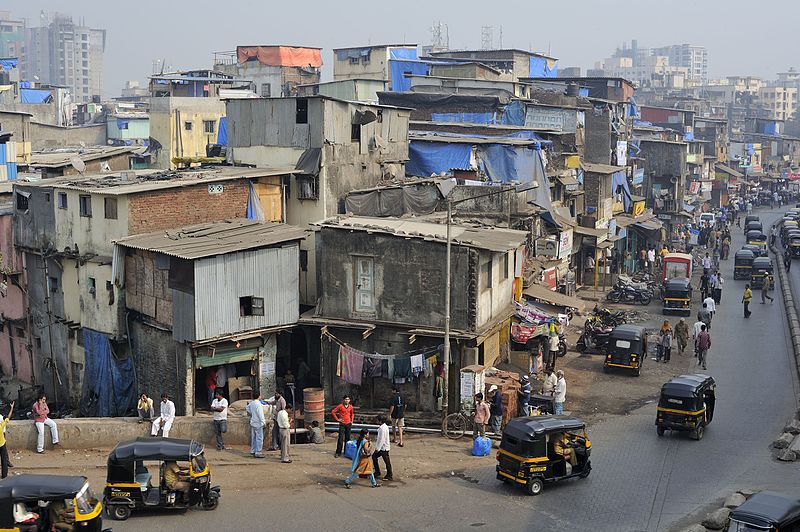

[quote]Slums are in a regulatory limbo; they are the twilight zones of urban plans.[/quote]At the heart of this end-state definition for a slum is an issue of urban planning and zoning—that of defining an acceptable planning paradigm for an informal settlement that does not fit into any of the slots in the current formal planning framework: there is no demarcation between residential and commercial; the buildings aren’t set back from the street or from their neighbours; and the road width (RoW) is between 5 metres to 1 metre—narrower than any of the mainstream urban roads, which go from arterial (42-60 metres) to sub-arterial (30 – 42 metres), to collector (30 -18 metres) to local (9-18 metres) and the smallest, sub-local ( 6-9 metres).

So how could an ex-slum fit into the formal fabric of a city? Are the buildings that stand cheek-by-jowl, on 10×10 sites to be considered legal, illegal, or quasi-legal? Can a formal retail store such as a D-Mart actually rent a space inside one of these ex-slums? The answer is that slums are in a regulatory limbo. They are the twilight zones of urban plans.

Picture courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

What we need is a new category of urban zoning, called High Density Low Income that allows for narrow lanes, buildings with no setbacks and higher FSI (floor space index, which defines the area that can built on a plot, across floors), mixed use to enable formal commercial space to coexist with residences, common (and possibly high-rise) parking so that residents can park their 2 (and sometimes even 4) wheelers, and walk to their neighbourhood homes.

[quote]There is an inescapable link between our pin codes and our destiny.[/quote]With such a new zoning provision, we can conceive a three-pronged approach to slum-free cities: first, provision of clear, free title to the residents, so that they enjoy the same privileges that the middle-class and rich do, of using property as a tangible asset; second, to upgrade the infrastructure and services in the slum, providing water, power, and sewage connections to individual homes, the collection of solid waste, street lighting and neighbourhood security and police support; and third, the creation of high-density, low income zoning that allows individual property owners to upgrade their homes without risk, rent out their properties to formal commercial establishments, that then provide services to the neighbourhood, and offer local employment.

Related article: ‘Project spending’ can only take our cities so far

Earlier this month, an ‘Opportunity Atlas’ report was released in America—a joint initiative by the US Census Bureau and Harvard and Brown Universities. Using hyper-local socio economic data, the study covers 20 million children, and finds a significant link between where children grow up and the outcomes of their lives in adulthood: across income, criminal conduct, teen pregnancies. The study concludes that growing up in better neighbourhoods, with better infrastructure, around people who have jobs, is more likely to help children of low-income families escape poverty and improve social mobility outcomes .

While there is no similar study for India’s slums, it is hard not to believe that this would be true here as well—that there is an inescapable link between our pin codes and our destiny. Improving slums to become neighbourhoods is a realistic approach to improving social and economic outcomes, and actually creating a slum-free India. The destiny of millions of slum dwellers depends upon our policy makers getting this right, and soon.

This article was originally published in Hindustan Times. You can view it here.