The Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) was launched in 2001 to achieve universal elementary education. It aimed at providing free and compulsory education to all children aged 6 to 14 years, bridging gender and social gaps in education, and enhancing learning levels at scale. The programme was later supported by the 86th Amendment to the Indian Constitution (Article 21A)—a landmark step in the country’s commitment to education that enshrined the right to education (RTE) as a fundamental right. Finally in 2009, the passage of the RTE Act cast a legal obligation on the state and central governments to execute the fundamental rights of a child. It laid the constitutional groundwork for ensuring that every child in India has access to free and compulsory education. While the amendment provided the legal framework, the SSA was the operational arm that implemented the RTE on the ground and worked towards achieving the goals of universal access, retention, and improved learning outcomes.

Today, the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 promises the delivery of quality education, aiming not just for access, but also for every child to receive a well-rounded education with equitable learning opportunities. To achieve this goal, the policy proposes expanding access to education to include the age group of 3 to 6 years, establishing the learning foundation through a focus on literacy and numeracy, enhancing teacher education, and emphasising continuous professional development for all educators.

To its credit, NEP 2020 aligns with the UN Sustainable Development Goal 4 and meets the emerging needs of this century as it focuses on preparing children for opportunities in a changing world. While the NEP has received criticism for certain shortcomings, it also presents significant positives. One advantage is its prioritisation of quality, affordability, and accountability as essential foundations for India’s education system. For example, it introduces a flexible curriculum with multiple entry and exit points in higher education, allowing students to choose subjects based on their interests. It has also suggested establishing a new regulatory body for higher education and promoting autonomy for institutions. In addition, the NEP aims to empower future generations with essential skills and mindsets, build a thriving environment for children, and boost the economy of a developing nation with a skilled workforce.

However, without necessary amendments to the RTE Act, policies shall remain mere policies, lacking clear avenues for effective implementation and measurable impact. As part of our work at ShikshaLokam, we orchestrate the coming together of diverse actors—the government, civil society, market players, and academia—towards public school improvement programmes led by education leaders themselves.

We believe that certain amendments to the RTE Act, as recommended below, can ensure that policies translate into tangible improvements in student learning and development, and are collectively implemented through different relevant institutions.

Amendments to RTE Act to make NEP 2020 more effective

1. Universalisation of free and compulsory education

The RTE Act (2009) mandated free and compulsory education for children aged 6 to 14 years, but early childhood care and education (ECCE) was not explicitly included. Introduced in 2013, the National ECCE Policy calls attention to holistic development and active learning for children under six and Anganwadi Centre (AWC) systems were imagined as the delivery channels for it. However, pre-school education has only been a small component of AWC services, with nutrition and immunisation being the main focus areas. It was only in 2018–19 that provisions were made to allocate funds for pre-primary education through the Samagra Shiksha scheme. While several states have since implemented it, the extent of the availability these funds and their effective use varies significantly. These gaps highlight the need for a comprehensive and integrated approach to ECCE, and hence it is among the key priorities of NEP 2020.

The NEP proposes expanding the age group for universalisation of free and compulsory education to include ECCE. This refers to structured learning experiences that introduce children to foundational concepts and support motor development, language acquisition, and building of problem-solving and social skills.

Universalising free and compulsory education for ages 3 to 18, along with providing necessary ECCE infrastructure (suitable classrooms, appropriate learning materials, play areas, nutrition, health and sanitation facilities), a robust curricular and pedagogical framework, and training for Anganwadi workers would ensure that children learn with greater ease in classrooms.

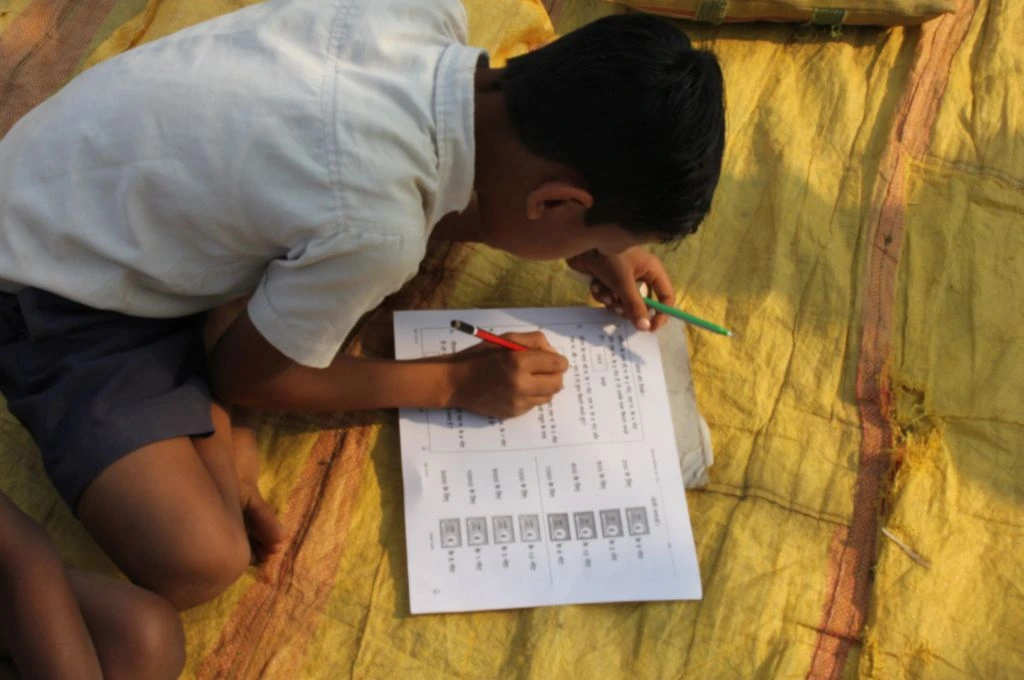

2. Conducting examinations at various grade levels

To reduce high dropout rates, especially among disadvantaged students, the RTE Act initially implemented a no-detention policy that allowed students to advance to the next grade regardless of their academic performance. This was aimed to alleviate the fear of failure and encourage continued participation in education. However, research indicates that this policy has led to a significant decline in student learning levels.

To address this, the NEP has proposed introducing a system of regular assessments at key stages (grades 3, 5, and 8). Students who do not meet the learning levels in these assessments will be asked to repeat the grade, and the onus will be on teachers to ensure that the students achieve minimum learning levels.

Implementing timely assessments and tailored support mechanisms will guarantee that students’ learning needs are met and they acquire the requisite foundational skills. It can also prevent dropouts, improve the teaching–learning process by addressing learning needs early on, familiarise students with assessments, and potentially reduce stress and anxiety levels in later years.

3. Stronger evaluation of candidates for teaching positions

RTE mandates qualified teachers but doesn’t specify the exact qualifications or any continuous professional development (CPD). This lack of clarity has resulted in inconsistency with respect to teacher training, which in turn contributes to varied learning outcomes across schools.

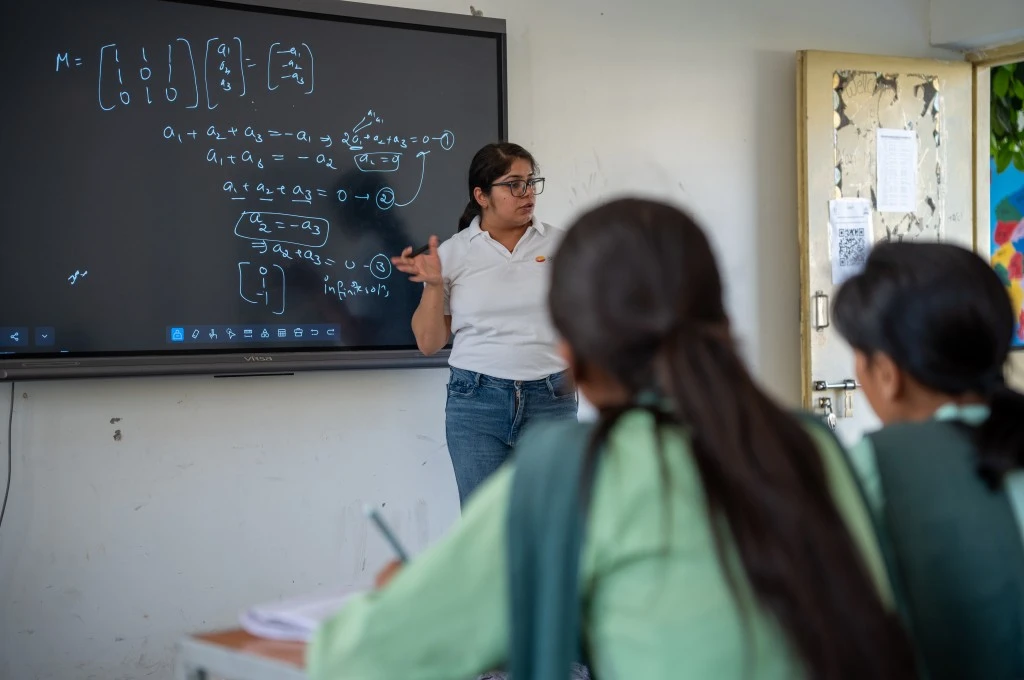

The NEP introduces more stringent teacher qualification standards through teacher eligibility tests (TETs) as well as classroom demonstrations and interviews to evaluate those applying for teaching across all stages (foundational, preparatory, middle, and secondary) of school education. The NEP further emphasises continuous professional development aligned with NEP 2020’s focus on pedagogical and technological skills.

On one hand, educators have welcomed the proposals for their likely impact on increased teacher quality and performance and scope to meet global teaching and learning standards. On the other hand, concerns have been raised about a potential shortage of qualified teachers and lack of clarity on upskilling of teachers who are already part of the system.

In any case, since a teacher’s teaching aptitude, subject knowledge, and pedagogical skills directly affect student learning, enhancing the evaluation process of candidates appearing for TETs would help identify individuals both qualified as well as passionate about the profession. This step would make teachers more accountable for their performance in classrooms and encourage them to improve their skills and knowledge. They will be better equipped to meet the diverse needs of students, including those with special needs or from disadvantaged backgrounds.

4. Formation of school complex management committees

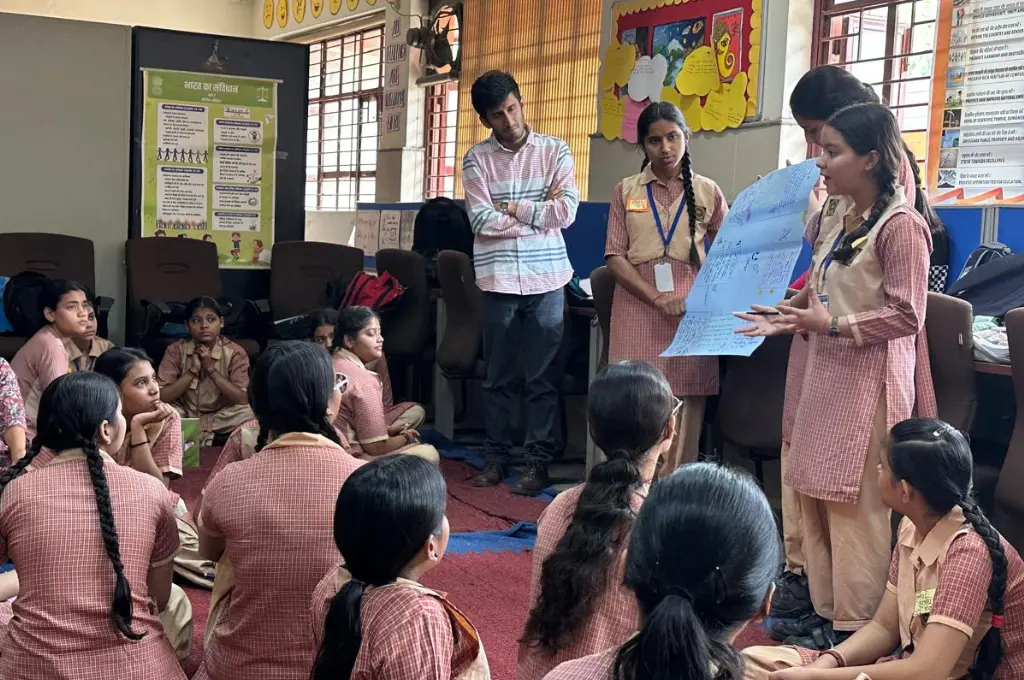

The RTE Act mandates the formation of school management committees (SMCs) in all government and government-aided schools. The committees are intended to promote transparency, accountability, and community participation in the management of schools. These bodies are composed of elected representatives of the local authority, parents or guardians of children enrolled in the schools, and teachers. However, they lack specific provisions for governance at a higher level.

The NEP envisions SMCs being integrated with local governance structures to facilitate better coordination and resource allocation. For this, it proposes the formation of school complexes comprising one secondary school and all other nearby schools, including Anganwadis, within a radius of 5–10 kilometres. This will ensure robust governance and monitoring across all schools in the cluster, with a regular assessment of the performance of each school to encourage adherence to consistent academic standards. In a way, the school complex will act as a ‘distributed school’ that caters to children between the ages of 3 and 16 years. These complexes will be responsible for crafting and implementing a plan outlining educational goals and resource allocation for each school within the cluster.

Since the idea of a school complex has not been implemented in India before, there is little literature or evidence on its effectiveness. Concerns include availability and efficient allocation of resources (material, infrastructure, human); overcrowding of spaces; and local sensitivities and cultural nuances being ignored due to compartmentalisation. However, studies on school clustering do offer insights into the potential benefits along with the challenges of the school complex model. Some positives include better coordination and resource sharing (teaching staff and facilities); reduced social isolation and burden of responsibilities that teachers experience in small-sized lower primary schools; and making schools more responsive to local needs and values.

5. Introduction of a transparent school ranking system

The RTE Act primarily emphasises the provision of adequate educational infrastructure, such as constructing new schools, modernising existing ones, and equipping them with essential facilities like classrooms, toilets, and drinking water. However, it overlooks specific standards and timelines for achieving these goals, which has led to differing interpretations and implementation challenges.

The NEP recommends the introduction of a public dashboard such as School Quality Assessment and Accreditation Framework (SQAAF) to benchmark standards and norms across schools so that there is better transparency, effectiveness, and recognition within the school education system.

This addresses the system’s access, equity, and quality in one go. It evaluates necessary resources and facilities, helping schools with infrastructure gaps improve access for all students. It also assesses and benchmarks teaching quality and learning outcomes, enabling schools to reveal and address disparities, particularly in teacher training and professional development. This will ensure that students from diverse and marginalised backgrounds receive equitable opportunities and support.

As a result of this, the parents will have visibility on various aspects of the learning environment and operations of the school system. As parents become more informed and involved, they are better positioned to support their children’s learning and engage more effectively with the school by advocating for necessary improvements. This contributes to a more supportive and responsive educational system.

There are concerns that the focus on rankings might lead schools to concentrate on achieving high scores rather than actually addressing deeper issues. Critics also point that metrics may not fully capture the diverse contexts of different schools, potentially overlooking unique challenges. However, at this juncture, SQAAF remains a valuable tool providing a framework for continuous improvement and a platform for deeper parent engagement.

—

Know more

- Read this article to learn what the NEP misses out on.

- Learn more about NEP implementation strategies.

- Read this article to learn how school assessments under the NEP could affect the quality of education.