Vocational education refers to learning modules focused on equipping students with technical skills required by an industry, a job, or a vocation. It aims to enhance the employability and entrepreneurial abilities of students, provide them exposure to a work environment, and generate awareness among them about various career options. In recent years, several policy-backed skill development initiatives have been supporting the push for vocational learning within schools. The government’s Samagra Shiksha programme, for instance, acknowledges the need to mainstream vocational education, where students from classes 9 to 12 are offered various subjects such as information technology (IT), agriculture, and tourism and hospitality as part of the school curriculum. The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 and National Curriculum Framework (NCF) 2022 also provide impetus to the vocationalisation of education.

Vocational learning is intrinsically linked with livelihood opportunities for children with special needs (CwSN) as well. According to this report, there are approximately 3 crore people with disabilities (PwDs) in India, out of which only 34 lakh PwDs have been employed across various sectors. Exposure to different skill-based learning modules including engineering, computer science, and other aligned streams can be a crucial step in enabling CwSN to access job opportunities that are available for them in the market.

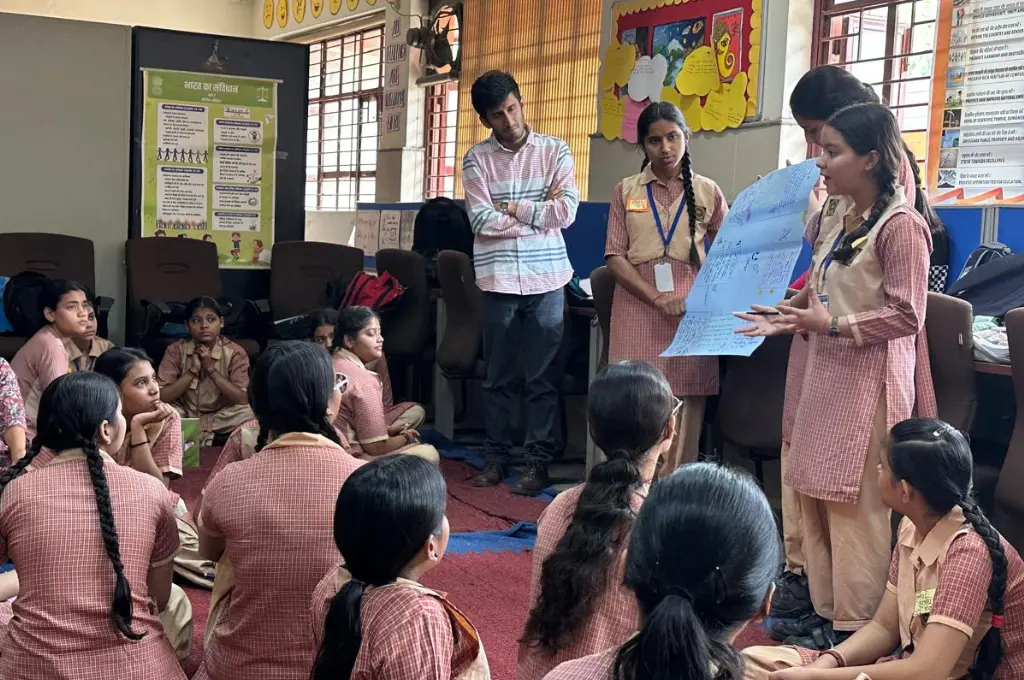

The inclusive education mandate of the Samagra Shiksha programme, in fact, has dedicated provisions for CwSN. However, many educators have flagged challenges in implementing the correct approach to vocational education for CwSN, especially neurodiverse children. For instance, Reshu Gupta, a vocational educator for hearing-impaired students in Poddar International school shares that many children in her class cannot complete the prescribed syllabus that has been designed keeping neurotypical students in mind. Under the vocational education syllabus, nine chapters on IT have been prescribed for a class. But Reshu explains that some students are unable to manage at the pace required to complete all chapters in an academic year.

Most educators in the field agree and point to the fact that in the absence of any concrete guidelines to help customise teaching or evaluation methods for different learning needs, children are usually promoted to the next class. This is an even larger issue when CwSN have to study alongside neurotypical students.

Is there an alternate approach for vocational education for CwSN?

If CwSN have to be provided with better market-linked learning through vocational curriculums then there is a need to focus on how it is currently being delivered in the country. Here are a few key areas that need attention:

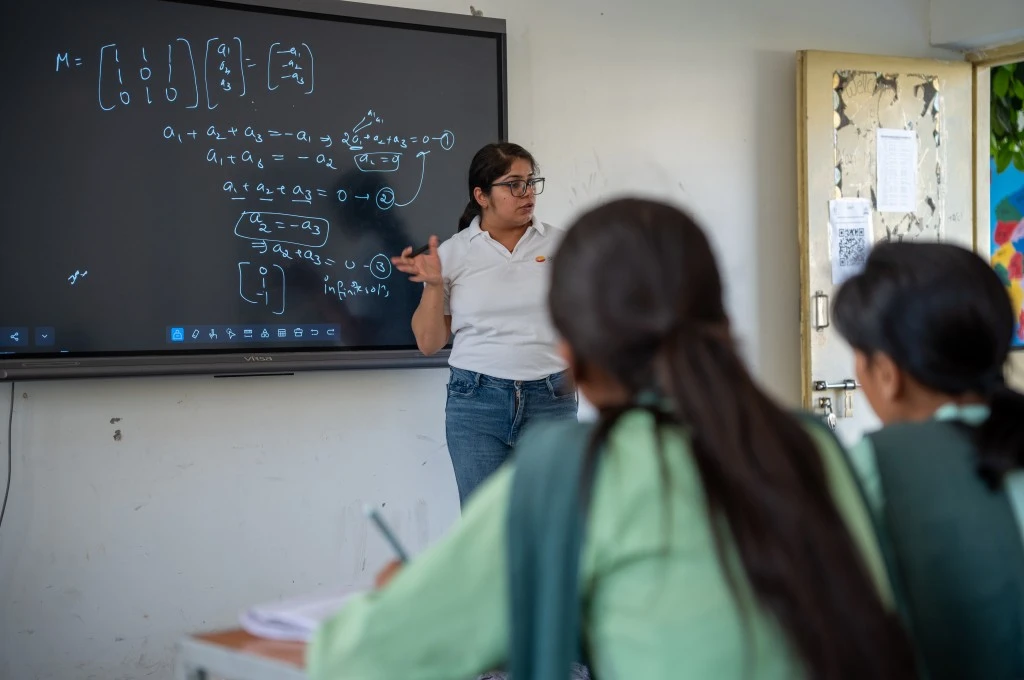

1. Pedagogy and curriculum

Identifying and adopting the right approach in vocational education for CwSN is critical. This can include introducing new methods for learning and teaching such as:

Multi-skill foundation course: A multi-skill foundation course comprises various subjects or units and focuses on hands-on learning. The subjects include workshop and engineering techniques, energy and environment, gardening, nursery and agriculture techniques, food processing techniques, and personal health and hygiene. Through an experiential learning-based pedagogy, the multi-skill foundation course aims to promote employability and increase the uptake of vocational skills among students. At present, the course is offered to students in classes 9 and 10 across schools in India.

As Sunanda Mane, the managing director of Lend-A-Hand India, points out, this course not only helps students understand what they want to pursue in higher classes but also provides an opportunity for teachers to assess students’ capabilities and interests in different areas and recommend subjects for classes 11 and 12. When it comes to CwSN, this can prove extremely useful as it will allow students and teachers to work together and hand-pick subjects that the students can pursue later. However, there is a need to further optimise this course for CwSN. This will require mapping capabilities for different disabilities and accordingly building the capacity of teachers to cater to the children’s needs.

Multidisciplinary approach: Every child with special needs requires a uniquely designed learning programme that may include assistive devices such as Braille or speech output devices, mobility aids, or therapeutic interventions such as physical or speech therapy. A multidisciplinary approach has been accepted as a valuable intervention for CwSN for effective inclusive education. It involves drawing from multiple disciplines and teaching methodologies, wherein students can choose what subjects they want to study and how they want to study them. It provides flexibility and helps them gain perspective and knowledge in different ways. For CwSN, a multidisciplinary approach allows for teaching and learning methodologies to be designed according to their needs. For example, in IT classes, an autistic or hearing-impaired child might grasp chapters at a different speed. A child may be quick to understand a chapter on website design but may find it difficult to get through chapters on coding. Therefore, the selection of chapters and the props, assistive devices, and lab would require customisation.

Meera Shenoy, managing director of Youth4Jobs, an organisation that is working on providing job opportunities for PwDs, further elaborates on the importance of a multidisciplinary approach. “Schools are the building blocks of life, more so for a vulnerable segment like CwSN. The complexity lies in the fact that there are 21 disabilities recognised by the PwD Act, many of which require a specialised approach, therapeutic interventions, and assistive technology. Providing multidisciplinary options needs cohesive collaboration between the school’s administration, teachers, and parents, which will help such children in progressively improving adoption of trade and life skills,” she says.

However, adopting a multidisciplinary approach or incorporating a multi-skill foundation course in the curriculum may not be feasible for all schools, especially government schools with limited resources and issues such as teacher shortages, lack of infrastructure, or even inflexibility in customising teaching lessons and subjects according to the needs of the children due to the volume of work. Support from other key stakeholders, including the government—in terms of policy mandates—and industry players—in terms of an employment pathways—is critical in making vocational learning and teaching methodologies more inclusive across states and schools.

2. Policy considerations and frameworks

A comprehensive framework outlining the adoption of more inclusive teaching methodologies by teachers and school boards is imperative to help develop curriculums that cater to the needs of CwSN for vocational learning. This can include:

Creating detailed policy education frameworks for CwSN: There is a need for detailed frameworks that cater specifically to CwSN. For example, the National Credit Framework recommends learning hours–based credit systems where students will have the flexibility to choose subjects from science, arts, and other disciplines. This can prove especially beneficial for CwSN, who may learn different subjects at a different pace. However, the framework makes no special mention of CwSN when it comes to flexible learning modules. Similarly, the NCF, which was released for consultation in 2022, provides a pathway to realise the vision of the NEP, but does not lay down a road map for education for CwSN. For example, the framework gives an illustrative standard for curricular goals and a fairly exhaustive explanation of competencies required for different classes, but does no such thing when it comes to CwSN.

Policymakers need to adopt a similar approach for CwSN and include policy suggestions for them under a separate section. Considering the limitations in designing curriculums for CwSN, inclusion of several illustrative use cases will help special educators in implementing inclusive teaching techniques by referring to the framework. This section can list the different types of competencies and detail how teachers can customise the curriculum of each subject for children with different disabilities.

Accommodating different kinds of disabilities: The Skill Council for Persons with Disability (SCPwD) was set up as a national body with the aim to recommend industry-linked curriculum skills to PwDs. However, their classification of vocational jobs is primarily based on physical disabilities. The current list of recommended subjects based on disability has no specific guidelines and suggestions for children with intellectual disabilities. However, if implemented correctly, the NCF provides flexibility that can be leveraged to recommend infrastructure, curriculum, and models aligned to the needs of children with intellectual disabilities in consultation with the special educators working with them. This will help equip CwSN with the appropriate skills that they require for jobs.

3. Infrastructure and industry linkages

When it comes to vocational training for CwSN, providing assistive devices, mobile skill labs, and customised hands-on training are important aspects of creating a solid curriculum. However, for CwSN to progress to meaningful livelihood-linked pathways, it is important that relevant elements of vocational training are interlinked in the curriculum with internships or industry exposure at the school level. This could include interactions with professionals through webinars, workshops, and internships as well as job-specific skilling modules. For example, CwSN interested in hospitality can attend trainings for soft skills related to the sector. However, most educators or schools may not be directly connected to industries or they may not have the knowledge to provide industry-specific skilling. Therefore, in order to create a smooth school-to-work transition for CwSN, it is crucial for schools and industries hiring PwDs to work in tandem, as these businesses may already have a dedicated budget, induction training modules, and special hiring programmes in place.

Vocational education is an integral component of education for CwSN, as it can be a catalyst for livelihood opportunities and can empower CwSN to lead a dignified life. Educators, policymakers, and private players must collaborate to devise market-linked learning pathways that can enable CwSN to adopt critical work and life skills.

—

Know more

- Read this report on the state of education for India for children with disability.

- Read this article to learn how COVID-19 affected inclusive education in India.

- Read this blog to learn more about multidisciplinary individualised education programmes.

Do more

- Provide feedback on the draft of the National Curriculum Framework here.