In the Indian context, decision-making, policy design, and implementation are often hierarchical in nature. In the education sector, resources must flow from the central government to the state departments and then to the district and local administrations in order for the benefits of national programmes to reach students. During the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic, when not much was known about the disease, national and state-level decision makers didn’t know what to do beyond immediately shutting down all schools across the country. Decisions pertaining to the creation of content for at-home learning and the reopening, curriculum, and instruction design of schools were made centrally through the first months of the pandemic. However, the trajectory of the pandemic meant that each region witnessed local variations in the transmission of COVID-19. As a result, schools in districts with limited spread were also forced to remain shut.

Interestingly, in Maharashtra, the districts themselves decided on when they want to open schools at their level. Since the severity of the pandemic differed from district to district at any given time, administrators were able to respond to their local situations. This led to 20,000 schools reopening in Maharashtra while lockdowns and school closures persisted at the national level. Additionally, we saw many examples of how teachers and communities took ownership of students’ education by pooling their own resources, be it by traversing large distances to reach students, collecting funds for infrastructural needs, or simply providing the necessary time.

These small local initiatives were successful in overcoming a larger problem that was difficult to address via national or state-level policies. The effectiveness of these efforts during the pandemic presents a strong argument for decentralisation, where empowered stakeholders can solve larger problems at the local level.

Why does decentralisation work?

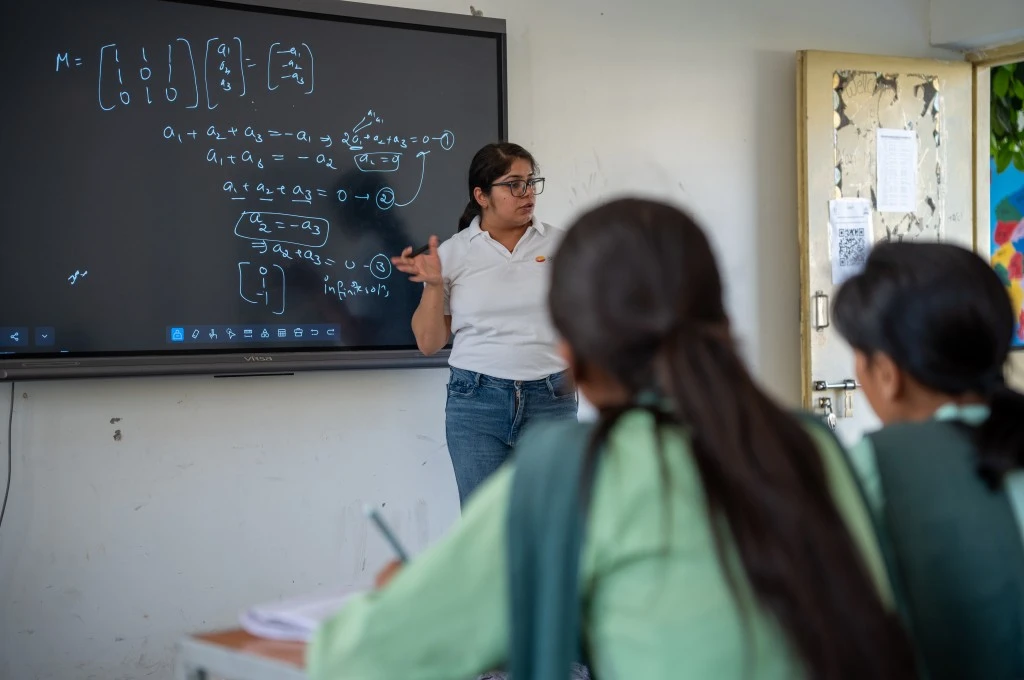

From the perspective of programme implementers, decentralisation is of high value as it helps improve the efficiency of programmes. In the education sector, teachers regularly receive trainings from master trainers, which creates a higher chance of information and knowledge loss at each level. One civil society member working closely with the local administration explained some of the issues present in a centralised system through the example of Maharashtra’s recent foundational literacy and numeracy programme: “A foundational literacy and numeracy programme would have already commenced in many districts, given that district administrators are currently aware of the large learning loss students are facing and the need for such a programme. But, in this case, the teacher training will occur through a central programme or through some measure from the state. But when will it occur? What will it cover? The district administration does not know. The district wants to conduct training, but it will have to communicate with the state and acquire its permission. Even if it receives permission, the content may overlap and cause the teachers to become disinterested. The training goes from the centre to the state, district, block, beat, and cluster. This is a very long chain, and it takes a lot of time. But at the district level, it is much quicker to implement.”

Swadhyay—a programme initiated by the Maharashtra government and driven at the state level by the SCERT—provided WhatsApp-based bots to assess student performance.

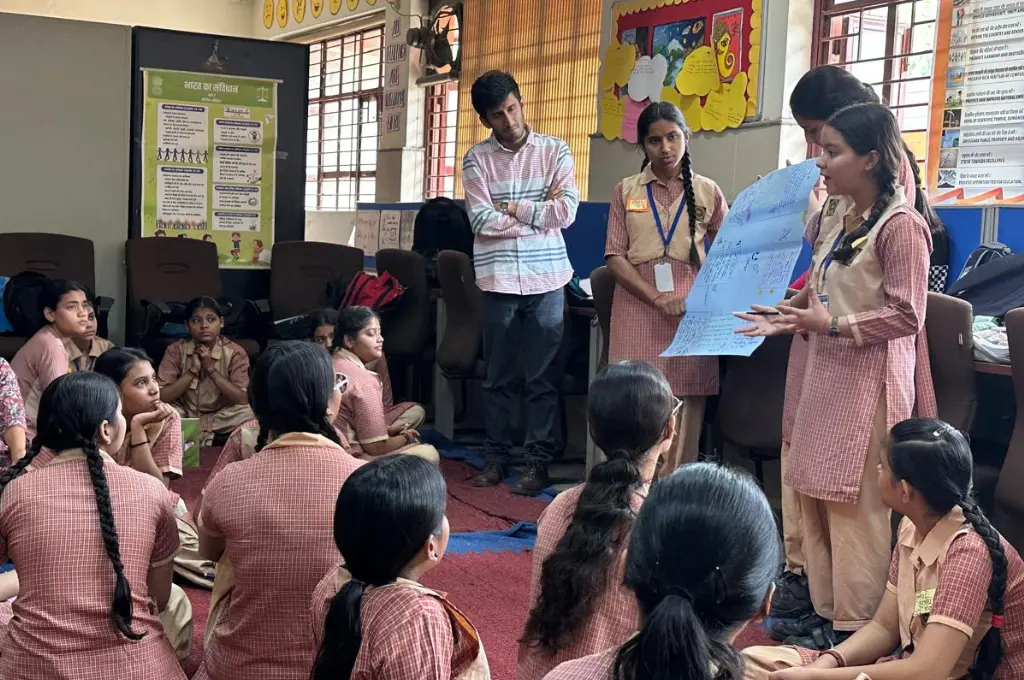

Another key argument for decentralisation is that it focuses on the micro needs of communities that differ by place and person. Even within a district, the needs of students in tribal areas differ from those of students in rural and urban areas. If there is a high degree of decentralisation, programmes can accommodate this variance.

An infrequently discussed aspect of decentralisation concerns ownership among local stakeholders. For instance, Swadhyay—a programme initiated by the Maharashtra government and driven at the state level by the SCERT—provided WhatsApp-based bots to assess student performance. While this programme required internet connectivity, its uptake in urbanised districts such as Pune and Mumbai was surprisingly low in comparison to other, more rural districts. According to those working closely with the administration, a key reason for this was the low level of ownership among district officers.

Contrastingly, in Pune district, other programmes run by district administrators witnessed wider implementation and reach. For instance, the District Institute for Education and Training witnessed an elevated level of effort and involvement from staff members when implementing a parent engagement programme. A greater sense of programme ownership drove those involved to feel more connected to their work. Often, the belief in the programmes that local administrators design or implement on their own is stronger. As a result, these programmes can reach a higher number of stakeholders.

How can we decentralise education effectively?

1. Leveraging gram panchayats

Gram panchayats—the smallest political unit at the village level—are often made up of parents of students or elected representatives who answer to parents and schools. As engaged community members, they can mobilise individuals, gather funds, and strive to obtain the necessary permissions for spending. These bodies can also be leveraged to unlock existing funds in service of schools and education. For instance, in Maharashtra’s Nashik district, local administrators and nonprofits made efforts to spread awareness about how the MNREGA scheme, which guarantees employment by commissioning public works ranging from irrigation to sanitation, transportation, and infrastructure, can be used to mobilise funds for school-related infrastructure projects as well.

2. Using data for decision-making

The use of data to monitor and modify programme implementation can also be extremely effective. By unlocking data collection and review mechanisms for monitoring programmes, local administrators can be empowered to drive implementation. In the case of Swadhyay, local civil society collaborators observed that once block education officers and school administrators were provided access to data on the reach of the programme, it helped them promote it in their specific jurisdictions to improve the programme’s efficacy.

3. Empowering local-level officials

Lastly, it is important to empower district officials to scale single-school innovations to the entire district. For instance, officials in Nashik decided to scale the Gully Mitra (street friend) programme in their jurisdiction. Through this programme, teachers, educated community members, and older students could provide support or learning spaces for students at the community level. This programme was found in all districts in some form or the other, such as Vidhyarthee Mitra (study friend) or Shezar Mitra (neighbourhood friend). While the programmes were structurally similar, enabling block officials to tailor the programme to local needs allowed them to organically scale the programme with relative ease and implement it in each jurisdiction.

Addressing the barriers to effective decentralisation

While there are many benefits of decentralising the implementation of education programmes and policies, the various factors that might act as barriers need to be considered. A key concern remains the lack of capacity among local administrators, particularly in terms of their ability to use data to improve programmes and drive decision-making. Additionally, effective planning and implementation may require coordination between different departments or bodies. This often becomes a major roadblock due to a lack of coordination and vested political interests. While programmes can be implemented at the local level as per requirements, it can become very difficult to aggregate information for statewide programmes to review progress or track goals.

Harnessing local efforts and including more stakeholders is the future of efficient programme implementation.

While the process flow in programme implementation is linear in nature, if you look closely, there is another whole ecosystem governed by individual relationships, power dynamics, and motivations. Programmes usually play out very differently when looked at with a bottom-up lens. These softer elements are often obscured in our linear understanding of how policies work. The pandemic has exposed the various weaknesses of the entire top-down process flow, where last-mile implementation challenges are exacerbated by a lack of motivation, ownership, and capacities.

Harnessing local efforts and including more stakeholders is the future of efficient programme implementation. By providing street-level bureaucrats with decision-making agency, opportunities to build capacities for programme design and implementation, and structures for multiple departmental priorities to converge, we can unlock the potential of public systems and improve public service delivery. As the pandemic revealed, decision-making can be decentralised to a regional level to ensure the continuity of education based on prevailing conditions. Empowering district officials to make decisions on in-person schooling and instructional design, exploring innovative sources of local funding, and assigning existing officials as nodal officers for quick decision-making are a few possible ways to achieve this decentralisation. As a result of these, we have witnessed innovations in education, the mobilisation of local and state resources, and higher levels of ownership during programme implementation.

—

Know more

- Learn more about the key challenges middle managers face when implementing education programmes.

- Read this article on ensuring a safe return to school for all children in the wake of the pandemic.