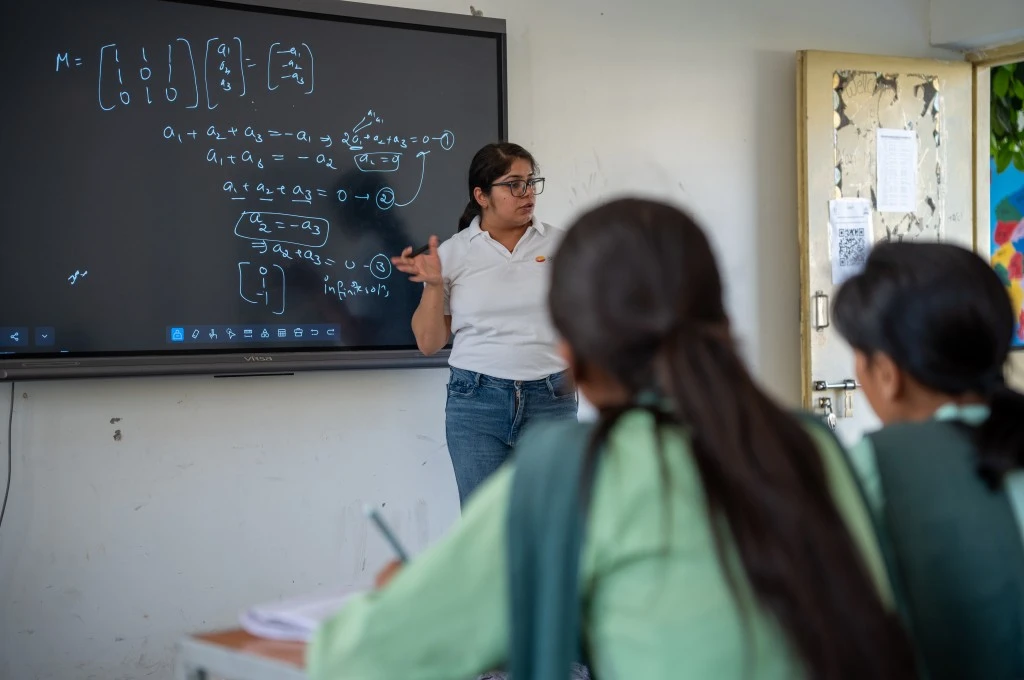

In 2018, the Delhi government launched its ‘happiness curriculum’ across several public schools. This is a class taught alongside other core subjects such as maths and science, and comprises three main aspects: mindfulness meditation; stories to promote responsibility; and activities meant to prompt self-reflection by students about their thoughts, emotions, and behaviour. Delhi’s education minister remarked that such a curriculum was needed to create ‘honest and responsible human beings’. The National Education Policy (NEP), 2020, is explicit about the need to include socio-emotional learning (SEL) in school curricula, while also emphasising the importance of counselling and mental health services in schools. Claims about SEL being the new frontier of school-based mental health laud its efficacy in facilitating long-term academic and career accomplishments.

The minister’s stated intention may seem valid, aimed at youth well-being. However, in its very assumption lies the problem: that teaching children to be ‘honest and responsible’, which are already subjective markers, is equivalent to supporting children’s mental health and addressing its multifaceted determinants.

The catch-not-all: Socio-emotional learning frameworks

The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) in the USA lists five broad competencies in SEL curricula: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. Interpretations of these competencies often yield in-school activities for building empathy, emotional regulation, acquiring perspective, cooperation, handling failure positively, and gaining patience. While SEL programmes are often promoted as aiming to create spaces—which are indeed few and far between—for the emotional worlds of children, critics argue that SEL serves, instead, as a behaviour modification programme. According to them, it lacks the critical lens needed to look at systemic oppressions which are linked to children’s emotions, behaviours, and mental health.1

The oft-quoted goals and success impact findings of SEL programmes invoke increased attendance in school, better relationships between students and teachers, and the improved academic performance of students ‘at risk’. Helping students achieve obedience, attendance, and academic measures of success are, however, primarily school system needs that do not necessarily converge with students’ overall well-being needs. This raises questions about the ultimate purpose of SEL programmes, and their approach to student mental health. As some scholars have argued:

“Educators…must begin by asking themselves about purpose and outcomes: Are we teaching individual students to manage their emotions and behaviors simply for the sake of upward mobility, and therefore continuing to alienate dispossessed and historically subjugated peoples through an erasure of social resistance? Or are we teaching students to recognize and re-claim their emotions and relationships as fuel for political inquiry, radical healing, and social transformation?”2

The ‘evidence’ markers of success through SEL programmes are also due for an unpacking.

One way to determine whether an SEL programme functions to benefit the school system or its students is to see if students take their learnings from it beyond school—whether they find the skills/learnings meaningful outside school contexts as well. One study found that the relevance of SEL skills outside of school depended not only on the cultural and other beliefs about emotional expression that students held, but also on their exposure to prejudice, discrimination, violence, and oppression in forms such as racism.3 For example, some surveyed students spoke of how aggression, which is discouraged in most SEL frameworks, was the only way to support and defend oneself on the streets. This finding illustrates the faulty construction of most present-day SEL frameworks, which consider neither family nor community contexts. Moreover, they do not account for the structural issues that impact the mental health and emotional world of marginalised children differently than their privileged peers. Consider a student facing violence at home, in their community, or even in their walk to and from school, due to their gender expression, caste, or disability: Are classroom-taught recipes for ‘successful’ socio-emotional responses—for happiness, even— likely to serve them well?

While SEL teachers may encounter students only within classroom settings, the general lack of attention towards students’ before-school and after-school realities raises concerns about SEL’s efficacy in supporting children. Even long-time proponents of SEL movements are lamenting the inherently exclusionary nature of most SEL frameworks and programmes today, and their being limited to the classroom.

The onus: On whom?

To assume that gaining ‘pro-social skills’ is a key method for addressing, or preventing, systemic adverse experiences that harm children’s mental health reflects an understanding that is not only incomplete, but also dangerous. It replicates problematic meritocratic messages already found in educational spaces—that an individual’s situation (of, say, success or failure) remains, primarily, the individual’s responsibility. As the scholars quoted earlier put it:

“Even with these well-intentioned efforts to address social and emotional learning, schools will continue to be institutions that…place the onus of social and emotional health on the very young people whose social stressors have been shaped because of dispossession and marginalization. This miseducation is hegemonic because it treats students’ personal frustrations and social discontent as something that needs to be remedied in them as individuals. In reality, though, the social and emotional health and well-being of…multiply-marginalized people [has] much more to do with their alienation from resources born [of] their oppression.”4

SEL programmes claim to be inclusive and accessible, yet ironically their content can also exclude. Teachers must consider that while some students may comfortably carry socio-emotional learnings beyond the classroom, others may experience them as yet another way to suppress and delegitimise diverse survival needs (such as justifiable anger) and reduce them to single-dimensional formulae (anger = bad). SEL must guard against training young people to ‘successfully’ suffer the systems that categorically fail them. The ‘evidence’ markers of success through SEL programmes are also due for an unpacking. Along with SEL, other evidence-based practices in educational systems have also been criticised for their forcible acculturation of groups on the margins, such as Native American communities in the USA.5

Today in India

The faults within Indian education systems do not end or begin with socio-emotional learning. Firstly, 29 percent of children in the country—most of whom belong to marginalised communities—do not complete primary education, challenging the assumption that we can equate school-based mental health programmes with children’s mental health programmes at large. Pandemic-induced lockdowns have only widened the gap, and made accessing the right to education more difficult as learning became online and remote. The NEP 2020 has itself been critiqued as jeopardising many key measures of inclusivity in educational spaces, leaving questions on the continued existence of affirmative steps such as reservation unanswered, and removing lessons on constitutional literacy, democracy, and diversity from curricula. Neither education policies in general, nor SEL frameworks specifically, mention measures to address the deaths by suicide among the country’s youth that affect marginalised communities disproportionately.6 Suicide remains one of the leading causes of death for young people under 30 in India.

With governments buying into the idea of SEL in schools, trepidation-inducing national education policies, a pandemic that has made structural inequities in all spheres unmistakably clear, and the speed with which SEL is gaining popularity among Indian nonprofits, a healthy critical review of SEL becomes necessary. It is imperative for mental health practitioners, educators, and allied professionals who are committed to anti-oppressive mental health work to caution against one-size-fits-all behaviour modification programmes, which are being marketed as mental health support. They must also demand changes within the oppressive structures and systems of education.

This article has been edited in parts for IDR. The original version was published in MHI’s fourth edition of ReFrame: Unpacking Structural Determinants

—

Footnotes:

- Camangian, Patrick, and Stephanie Cariaga. ‘Social and Emotional Learning Is Hegemonic Miseducation: Students Deserve Humanization Instead.’ Race Ethnicity and Education, 2021.

- Camangian, Patrick, and Stephanie Cariaga. ‘Social and Emotional Learning Is Hegemonic Miseducation: Students Deserve Humanization Instead.’ Race Ethnicity and Education, 2021.

- Farrell, Albert D, et al. ‘A Qualitative Analysis of Factors Influencing Middle School Students’ Use of Skills Taught by a Violence Prevention Curriculum.’ Journal of School Psychology, 2015, vol. 53, no. 3.

- Camangian, Patrick, and Stephanie Cariaga. ‘Social and Emotional Learning Is Hegemonic Miseducation: Students Deserve Humanization Instead.’ Race Ethnicity and Education, 2021.

- Rowe, Hillary L, and Edison J Trickett. ‘Student Diversity Representation and Reporting in Universal School-Based Social and Emotional Learning Programs: Implications for Generalizability.’ Educational Psychology Review, vol. 30, no. 2, September 30, 2017.

- Arya, Vikas, et al. ‘The Geographic Heterogeneity of Suicide Rates in India by Religion, Caste, Tribe, and Other Backward Classes.’ Crisis, vol. 40, no. 5, February 28, 2019.

—

Know more

- Read this article that discusses discrimination and the role that educational institutions can play for better collective mental health.

- Explore DLR Prerna’s resources for children’s mental healthcare.

- Read about how a mental health practitioner in Manipur supported her clients during the pandemic.