Thana village in Rajasthan’s Bhilwara district had been facing a predicament shared by many rural communities in India: They were struggling to secure adequate fodder for their livestock due to limited rainfall and the hot, arid climatic conditions of the region. In addition, mismanagement and encroachment of charagah (common land) ensured that the problem persisted. This situation left them with the distressing choice of either importing fodder from distant regions, which is costly and not affordable for all, or abandoning their animals. In the past, when transportation was a challenge, villagers had no option but to walk with their animals to Malwa in Madhya Pradesh around 400 km away, and leave them there for grazing. However, in 2006, with the efforts of a few concerned villagers who understood the problem and conveyed it to their fellow villagers, people collectively took action. They united as a community to protect their charagah from encroachers and transform it into a source of food security for their livestock.

This photo essay captures the community members’ journey of conservation, highlighting the challenges they encountered while developing and sustaining this model. It also showcases their unwavering commitment to both the animals and the environment as they continue to fight for the preservation of their common land.

Coming together for livestock and land

Thana village is home to approximately 1,200 animals, including cattle, sheep, and goats. Livestock farming is the primary livelihood of most people living here. Droughts are common and ensuring an adequate supply of fodder, especially from late winter to mid-summer, is a major challenge. Shyam Gujjar, a resident of the area, shares, “During the drought in 2022, many animals perished from hunger, particularly those abandoned ones that resorted to eating plastic out of sheer desperation.” Kalu, Shyam’s friend, adds, “We empathise with the stray animals, but it’s a struggle to feed our own livestock.”

During this period, feeding a single animal for survival itself could cost up to INR 10,000, and a significantly larger investment is required for them to thrive. Shyam explains, “During these months, the price of wheat stocks soars to INR 20 per kilogram or INR 600 per 40 kilograms. Just one animal would need at least 600 to 700 kilograms to survive and approximately 4,000 kilograms to thrive.”

Without common land, there’s also a loss of the sense of community.

Furthermore, the encroachment of common land by community members who wield social, economic, and political power worsens the problem for smallholder farmers. They are forced to allocate a significant portion of their earnings to purchase fodder, which is an expense they could cut down on if they had ample common land for their animals to graze freely.

Without common land, there’s also a loss of the sense of community. Shyam says, “Collective ownership differs from individual ownership. An individual can choose to build a 6-foot wall around his land and decide who is allowed and who is not. But with commons, the richest of the rich and the poorest of the poor have an equal stake. They can determine how they want to use it; the wealthy may use it for leisure, while the less fortunate can earn a livelihood.”

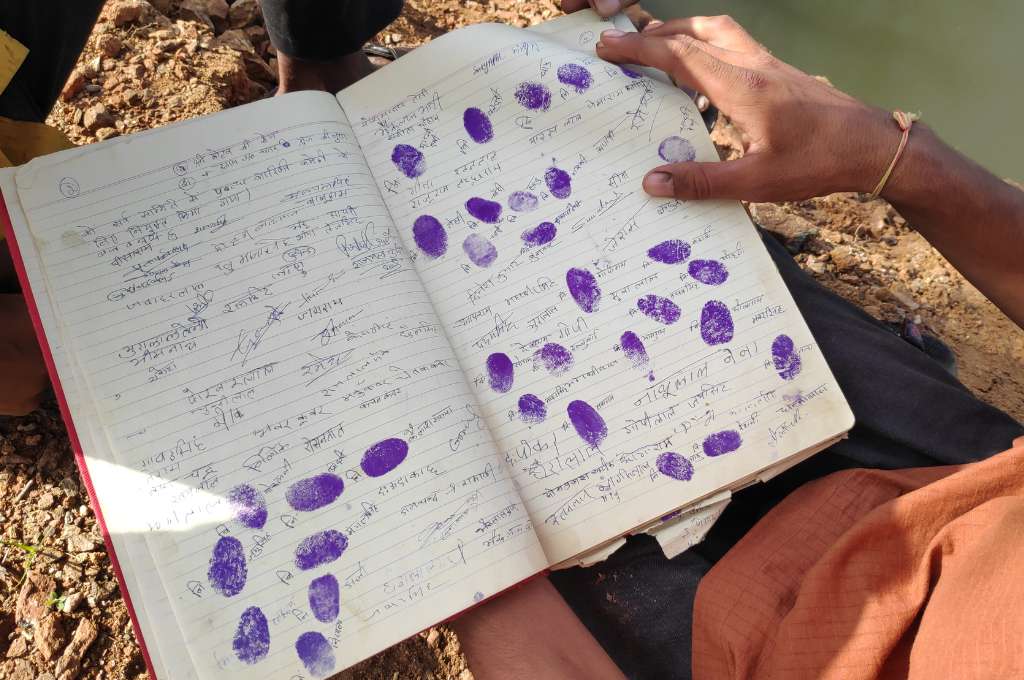

In 2006, Balulal Gujjar, Shyam’s father, took the lead in mobilising the village against encroachments on their shared land. The villagers recognised the critical importance of safeguarding and improving these resources for food security, and wholeheartedly supported the initiative. That year, an informal committee was formed, which collaborated closely with local authorities for the development of these lands. To ensure fair decision-making, the people of Thana established a structured system. They conduct meetings on the 5th and the 20th of every month to decide upon vital matters, such as when to allow grazing and setting grazing fees for the villagers, and share updates on encroachment removal and the identification of new encroachments.

While its inception was informal, the committee was officially registered as the Charagah Vikas Samiti in March 2021 under the Rajasthan Panchayati Raj Act, 1996, thus obtaining legal authority to mobilise local resources, raise funds, and seek government support for various development projects aimed at improving the living standards of the community. Under the act, the committee is legally empowered to make decisions concerning the management of these lands, ensuring equitable access for all residents, and enforcing regulations related to land use and environmental conservation.

Taking back the commons

Thana village has approximately 2,000 bighas of common land, nearly all of which were encroached upon at some point. Thanks to the persistent efforts of the Charagah Vikas Samiti, 10 percent (200 bighas) of this land has been successfully reclaimed from encroachers.

Kalu explains, “Reclaiming this land is quite challenging because the encroachers are often fellow or neighbouring villagers. We attempt negotiation first, but there are times when we have to invest our own resources and travel 100 kilometres to Bhilwara to file a formal complaint against the offenders.”

Encroachment tactics vary. While some individuals gradually expand the boundaries of their private properties into the common land, others create ramps for their cattle to cross over into the commons. People have also attempted to establish shrines and, in one instance, invited a baba (religious guru) to reside on the common land, thinking that people will be afraid of taking any action against him and so he can facilitate the takeover of the land.

The committee employs various methods to combat these encroachments. For example, when confronted with stone boundary walls built by the encroachers on the land, committee members dismantle them and reuse the stones to construct the commons’ walls. In cases involving the construction of ramps, heavy machineries such as bulldozers are summoned for removal. When a resident from a neighbouring village put up a stone shrine, Kalu took matters into his own hands, physically relocating the stones to near the homes of those who attempted to establish the shrine.

He explains that encroachers employ such tactics because shrines hold religious significance, making it unlikely for anyone to remove them out of fear of divine retribution. Shyam adds, “In the case of the baba who settled on the common land, we mobilised the entire village, making announcements using microphones and drums. By the time we all gathered, the baba had fled the area.”

Securing resources for the development of the reclaimed land

While removing encroachments is a significant achievement, developing the reclaimed land is equally crucial to make it productive and fulfil its role in ensuring food security for livestock. However, development in this context involves more than just financial resources. Shyam emphasises, “Beyond money, people have contributed their labour to develop this land. Individual families took on specific responsibilities, such as building sections of the boundary wall.”

In addition to monetary contributions and labour inputs, institutional support plays a pivotal role, and the Charagah Vikas Samiti facilitates these efforts. The committee collaborates with the gram panchayat, block, and district development officers to ensure the efficient use of government schemes such as MGNREGA and Mukhya Mantri Jal Swavalamban Yojana for planned land development. Most of the land’s development, including the construction of durable boundary walls, ponds, check dams, and contour trenches, has been accomplished through the coordinated utilisation of these schemes.

Shyam highlights, “Countless hands have contributed to the land’s development, with people from Thana village and neighbouring villages—some from as far as 8 kilometres away—coming to work on this land. We estimate that work worth more than INR 1 crore has been completed, benefitting the local community. While the financial benefit per individual may not be substantial, it’s far more equitable than money going into the hands of a single contractor.”

An estimated annual budget of INR 2.5–3 lakh is needed for the proper maintenance of the charagah.

To generate funds, the committee conducts auctions of grass and fruits harvested after the monsoon season, which earns them approximately INR 50,000. This money is used to hire a security guard for several months in the year to prevent stray animals from entering the charagah and to ensure that no one allows their animals to graze without permission. The guard is paid INR 6,000 per month.

Apart from the auctions, the committee lacks a regular income source. Shyam estimates that an annual budget of INR 2.5–3 lakh is needed for the proper maintenance of the charagah. These funds are required for boundary wall repairs, tree planting, and hiring of security guards for both morning and night shifts throughout the year. Kalu emphasises that support from the government or philanthropic foundations would greatly help in these endeavours.

Harvesting the fruits of conservation

When it comes to the benefits derived from the development of the charagah, there are two distinct categories. Firstly, there are direct advantages, primarily in the form of an extended fodder supply during critical months. This translates to substantial annual savings of approximately INR 6,000 per animal, if not more. Secondly, there are increased employment opportunities through MGNREGA, which not only boosts direct income but also allows nutritious fodder and thus healthier livestock.

For the people in and around the village, the reclaimed and replenished land also offers a place for peace and leisure. Shyam explains, “Kalu and I often come here to sit in silence, listening to the birds chirping.” Kalu describes the experience saying, “It’s so serene that if you come here hungry, you’ll forget your hunger.”

This profound sense of ownership and attachment to the land stems from the fact that the community members themselves reap the rewards of their labour. The beneficiaries extend beyond the human community. The village’s domestic animals, as well as wild creatures such as blue bulls and hundreds of bird species, enjoy the bounties of the land.

Shyam and Kalu say, “We plant different types of fruit and trees on the land. This benefits numerous wild animals and birds, providing them with nutritious sustenance and contributing to the overall conservation of biodiversity.”

To further enhance this effort, it is essential to strengthen the provisions for the Charagah Vikas Samiti. Kalu and Shyam say, “A source of regular income could help reinforce the system we have developed here. If the government can allocate an annual budget [for the upkeep of common lands], it would encourage more panchayats to establish samitis like ours—helping more people, animals, and the environment in general. Even private institutions and nonprofits can assist with funds for specific initiatives or contribute by sharing conservation knowledge and helping in improving our committee functionality.”

—

Know more

- Learn how an adivasi activist from Rajasthan composes songs to encourage the conservation of natural resources.

- Learn about sustainable livelihoods and resilience through community forest management.