READ THIS ARTICLE IN

खाण माफियांना गावाबाहेर काढण्यासाठी राजस्थानमधील एका गावाने एक अनोखी रणनीती वापरली आहे

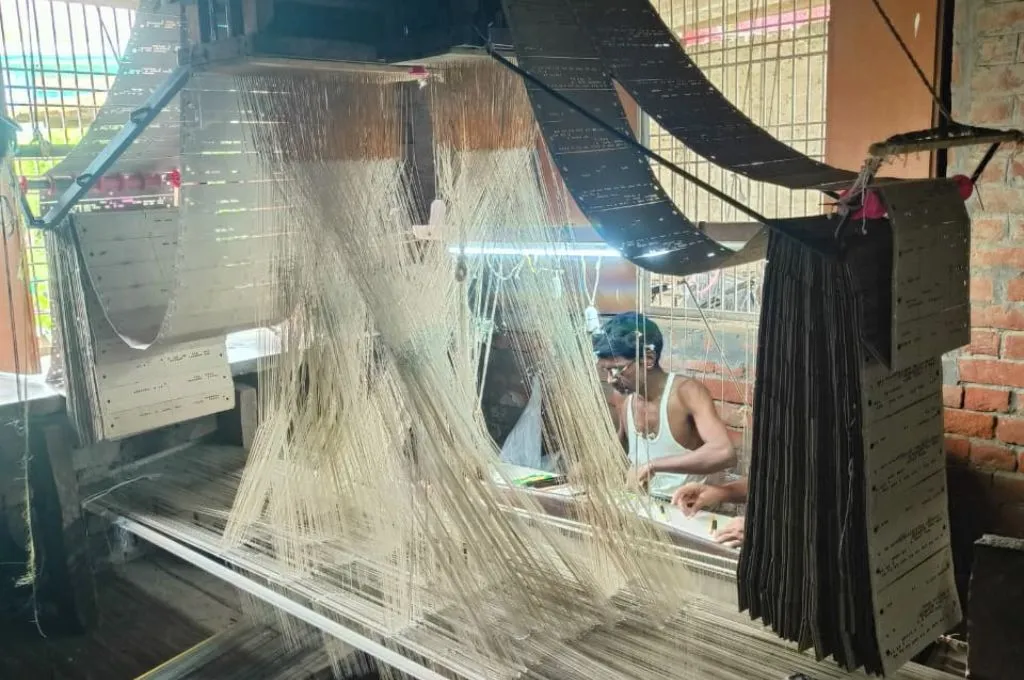

राजस्थानच्या राजसमंद जिल्ह्यातील राजवा गाव हे अरवली डोगर रांगांमध्ये वसलेले आहे. या गावातील रहिवाशांकडे शेतीसाठी मर्यादित जमीन आहे, यामुळे अनेकांना रोजगाराच्या संधी शोधण्यासाठी इतर राज्यात स्थलांतर करावे लागते किंवा उदरनिर्वाहासाठी पशुपालनावर अवलंबून राहावे लागते. महिला प्रामुख्याने मनरेगा अंतर्गत देण्यात येणाऱ्या कामांवर मजुरीसाठी जातात.

2014 पासून राजवा येथे खाण माफिया सक्रिय आहेत. त्यांनी संगमरवराने समृद्ध असलेल्या जमिनीचा मोठा भाग ताब्यात घेतला आहे, ही जमीन, बहुतेकवेळेला जमीन कायद्यांचे उल्लंघन करून, ते गावकऱ्यांकडून खाजगीरित्या खरेदी करतात किंवा भाडेतत्त्वावर घेतात . पूर्वी, या जमिनी कुरणांच्या जमिनी होत्या. सध्या, या प्रदेशात पाच सक्रिय संगमरवरी खाणी आहेत, ज्या एकत्रितपणे सुमारे 4 किलोमीटर लांब आणि 500 मीटर रुंद क्षेत्रात पसरलेल्या आहेत. खाण माफियांचा प्रभाव इतका मोठा आहे की या जमिनींवर गुरे चारण्याचा प्रयत्न करणाऱ्या लोकांना ते पोलिसांकडे नेण्याची धमकी देतात.

ज्यांच्या जमिनीत संगमरवर होता त्यांनी त्यांच्या आर्थिक गरजा भागवण्यासाठी आणि कर्ज फेडण्यासाठी जमिनी विकण्यास सुरुवात केली. परिणामी, गावातील अर्ध्याहून अधिक कुरणांच्या जमिनीचे उत्खनन केले जात आहे. एकेकाळी विविध कारणांसाठी – जनावरांच्या चरण्यासाठी, मनरेगाचे काम करण्यासाठी आणि लाकूड गोळा करण्यासाठी – वापरले जाणारे भूखंड हळूहळू मोठ्या आणि खोल खाणींमध्ये रूपांतरित झाले आहेत.

राजवा येथील ढोरा या गावात या भागातील पहिली खाण कार्यरत झाली, या आव्हानांना तोंड देत, या गावातील लोकांनी, ही नवीन सुरू झालेली खाण बंद करण्यासाठी पुढाकार घेतला. ज्यांनी त्यांची जमीन विकली होती त्यांनाही त्यांची चूक लक्षात आली आणि त्यांनी ती परत मिळवण्यासाठी गावातील इतर लोकांकडून मदत मागितली. परंतु खाण मालकांकडे ६० वर्षांचा भाडेपट्टा असल्याने, त्यांना प्रशासनाकडून कोणतीही मदत मिळू शकली नाही.

या परिस्थितीचा सामना करण्यासाठी लोकांना नाविन्यपूर्ण उपायांचा विचार करावा लागला. खाणकामाच्या ठिकाणी गावातील बहुतेक लोकांचे दैवत- देवतेचे एक मंदिर होते, जेथे लोक पूजा करतात. गावकऱ्यांनी एकत्रितपणे तोडफोड आणि हिंसाचार न करता शांततेत निषेध करण्याचा निर्णय घेतला, जेणेकरून त्यांच्या देवाच्या नावाने जमीन सुरक्षित राहील. ढोराच्या रहिवाशांनी त्यांचे सामान – पिशव्या, बेडिंग पॅक केले आणि मेंढ्या, शेळ्या, गायी आणि म्हशी यांसारखे पशुधनसोबत घेउन – संपूर्ण दिवस जमीनीचा ताबा घेण्याचा, निर्धार केला. सुमारे 150 लोक दररोज जमिनीवर बसू लागले, ह्यामुळे खाणकाम पूर्णपणे थांबले.

महिलांनी एक पाऊल पुढे जाऊन पर्यावरण वाचवण्याचा निर्णय घेतला, स्थानिक पातळीवर भाव म्हणून ओळखली जाणारी ही अनोखी पद्धत म्हणजे आत्म्याच्या भावना किंवा त्यांच्या शरीरात असलेल्या दैवी शक्तीची भावना व्यक्त करणे. ती अंधश्रद्धा वाटली तरी, समाजात तो अभिव्यक्तीचा एक वैध मार्ग आहे. खाण कंपनीला हाकलून लावण्यासाठी धोरण म्हणून, स्थानिक महिलांनी भावअनुभवल्याचे (अंगात आल्याचे) नाटककेले. असे दिसले की जणू काही दैवी शक्ती त्यांच्यात सामील झाली आहे, ज्यामुळे डोलणे, जप करणे, जमिनीवर लोळणे आणि एखाद्या आत्मा, देवता किंवा देवीमातेशी बोलणे यासारख्या अत्यंत भावनिक आणि शारीरिक क्रिया त्यांनी केल्या. मनरेगाच्या कामात पूर्वी गुंतलेल्या 30-40 महिला सुद्धा या निदर्शनांमध्ये सामील झाल्या. दहा जणांच्या गटात स्वतःला विभागून त्यांनी भावअनुभवला. दरम्यान, पुरुषांनी एरवी महिलांनी हाती घेतलेल्या घरगुती कामांची जबाबदारी स्वीकारली.

हे महिनाभर चालू राहिले. जेव्हा खाण मालकांना लक्षात आले की स्थानिक लोक हार मानणार नाहीत, तेव्हा त्यांना भीती वाटू लागली की इतर गावातील लोक या निदर्शनातून प्रेरणा घेतील आणि त्या भागातील खाण कंपन्यांनाही हाकलून देण्याचा प्रयत्न करतील, म्हणून त्यांनी ती जागा सोडून जाण्याचा मार्ग स्विकारला. गेल्या दोन वर्षांपासून ती खाण कार्यरत नाही. परंतु या परिसरात अजूनही चार कार्यरत खाणी आहेत आणि तेथे जास्त उत्खननामुळे पर्यावरणाचा नाश होत आहे.

ईश्वर सिंग हे एक सांस्कृतिक आणि सामाजिक कार्यकर्ते आहेत जे कामगार आणि शिक्षणाच्या मुद्द्यांवर काम करतात.

मूळ इंग्रजीतील लेखाचा मराठी अनुवाद करताना ट्रांसलेशन टूलचा वापर केला आहे. सुशील कुमार सडोलीकर यांनी अनुवादीत लेख तपासण्याचे व संपादनाचे काम केले आणि अंकिता भातखंडे यांनी याचे पुनरावलोकन केले आहे.

—

अधिक जाणूनघ्या: गुजरातच्या छोटा उदेपूर जिल्ह्यात वाळू उत्खननाच्या परिणामांबद्दल अधिक जाणून घ्या.

अधिक करा: लेखकाच्या कामाबद्दल अधिक जाणून घेण्यासाठी आणि त्यांना पाठिंबा देण्यासाठी mkssishwar@gmail.com वर त्यांच्याशी संपर्क साधा.