Think of a classroom in a school in India, and the image that comes to mind is that of a few children sitting in the first row listening to the teacher while the rest sit in their designated back seats, stay distracted, and are chided every once in a while, for being too loud or too mischievous. Often, parents and teachers alike believe that young children in school learn most effectively when they are disciplined, obedient, and listening quietly to the teacher. However, child development experts have iterated that active involvement and engagement of children through cognitive learning makes for a powerful alternative to the traditional classroom approach.

Cognition is the mental process of acquiring knowledge, and refers to how we think, pay attention, remember, and learn. Cognitive learning is learning through experience while building on one’s past knowledge. It is constructive, long-lasting, and it fully engages children in the learning process while discouraging rote memorisation. It is one of the most important precursors to acquiring academic skills. For instance, a child who has a good sense of pattern recognition will be able to apply this understanding to skip counting, making it easy for them to master the skill of multiplication.

What do the ASER reports say about cognitive learning?

Currently, India’s children sorely lack cognitive skills—a consequence of the absence of the cognitive learning approach in elementary classrooms. This dearth of skills is clearly evident in the findings of the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), 2019.

ASER is an annual citizen-led household survey that has been collecting data on children’s learning levels across rural India since 2005. ASER 2019 ‘Early Years’ assessed young children in the age group of 4-8 years in rural India on various developmental indicators. The results are indicative of a learning crisis that starts well before the elementary grades.

ASER 2019 suggests that a large proportion of children in the age group of 4 and 5 are unable to perform cognitive tasks expected of them.

ASER 2019 suggests that a large proportion of children in the age group of 4 and 5 are unable to perform the cognitive tasks expected of them. Out of children aged 5, only 51 percent could order by size, 47 percent could recognise a three-item pattern, 52 percent were able to solve a 4-piece puzzle, 82 percent could do a spatial awareness task, and 82 percent could sort objects based on colour.

The report finds a clear relationship between children’s performance on cognitive tasks, and their ability to do early language and early numeracy tasks. Out of those children aged 5, who could do one or no cognitive tasks, 15 percent could count single-digit numbers. This proportion increased to 69 percent for children who could do all five cognitive tasks. The difference in the performance reflects that cognitive skills are central to building children’s understanding of academic concepts.

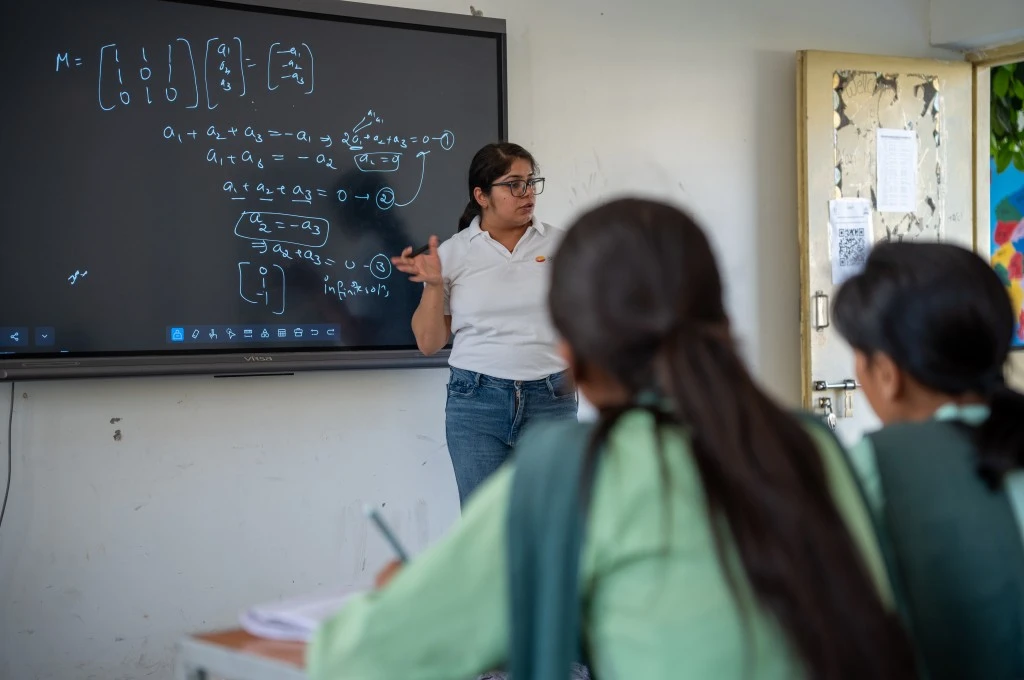

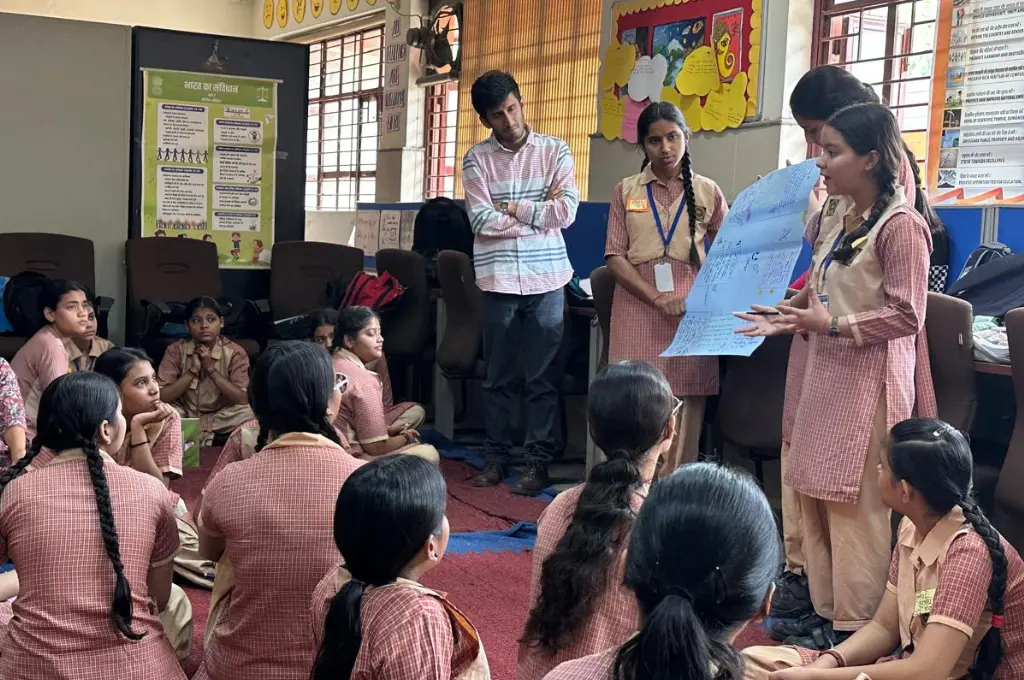

One of the ways through which cognitive learning can be effectively incorporated in elementary classrooms is through play. | Picture courtesy: Charlotte Anderson

As children progress to Standard I, their performance on cognitive tasks is still well below curricular expectations. Just 67 percent of children in Standard I could order by size, 60 percent of the children could recognise a three-item pattern, and only 55 percent children were able to solve a puzzle. According to the National Council for Educational Research and Training (NCERT) learning outcomes, children are expected to be able to do all these tasks by the end of pre-school. Even in Standard III, close to half the children are still unable to perform all three cognitive tasks.

As with children aged 4 and 5, this lack of cognitive skills reflects in their performance on academic tasks. Out of those children in Standard III who could do one or no cognitive tasks 20 percent were able to read a Standard I level text. This proportion increased to 63 percent among children who could do all three cognitive tasks—a jump of over 40 percentage points. This trend can be observed across all ages and grades, signifying the importance of cognitive development not only in pre-school but also in the elementary grades.

What’s play got to do with it?

One of the ways that cognitive learning can be effectively incorporated in elementary classrooms is through play. Play and learning are often viewed as being at odds with each other. When children are seen playing games like puzzles or doing activities like colouring, it is often believed that it is hampering their ‘study time’. Yet play is known to have a positive impact on learning and retention. A play-based learning approach involves the participation of children through activities, games, and peer learning.

India’s policies have reflected this model of learning in the case of Early Childhood Education (ECE) for years now, with the National Policy on Education (released in 1986), and the Right to Education Act (2009) advocating for a play-based environment of learning for children.

Along with this, NCERT has defined learning outcomes for pre-school that details what children should know at the end of each pre-school year. These outcomes focus in-depth on the development of skills such as cognitive, social and emotional, creative, and communication, through cognitive learning and play. The guideline also outlines child-centred pedagogical processes for teachers to achieve these learning outcomes.

Adapting a cognitive learning approach in school can go a long way in fostering progress in children’s learning and thinking.

However, as children transition to formal schooling, the focus of the policies shift from play, and cognitive development is side-tracked to make way for more structured and instructional approaches to learning that are content-oriented rather than skill or ability-oriented. The shift to school is a period of tremendous cognitive change for children, as they move to a formal setting where they are interacting with new people, places, and ideas. Consequently, adapting a cognitive learning approach in school can go a long way in fostering progress in children’s learning and thinking.

An analysis of the NCERT’s prescribed learning outcomes for elementary grades reveal a lack of continuity in what we expect of children in pre-school and in school, with a big leap in difficulty during the transition between these stages. Although its learning outcomes in primary grades do incorporate some cognitive and play-based pedagogical processes such as teaching with material and social interaction, these are neither holistic nor sufficient.

We need to rethink how learning takes place in elementary grades

The path to incorporating play into elementary classrooms is not easy, especially in Indian schools which have long been fostering rote memorisation and discouraging children from thinking differently. This move will require an enormous shift in the attitude of everyone involved—teachers, families, communities, policy-makers, and the government.

For policy-makers, the challenge will be to move past the norm of what is considered acceptable in a formal classroom, and to develop pedagogical processes with play as the central element of learning. On the implementation front, the big challenge will be to train teachers to move away from the traditional and instructional forms of teaching, by reforming their ideas of teaching-learning. Acceptance for a more experiential approach to teaching-learning will have to be built within the community of teachers.

In spite of the challenges, an effective way to make learning more fruitful in elementary grades is for systems to encourage learning based on active and responsive pre-primary ethos. Instead of clamping down on children’s curiosity and ideas, they should be given the freedom to interact with one another, taught through experiential learning, and encouraged to explore new materials. This will create an environment that is more playful and conducive for cognitive learning. It will also yield what we hope to achieve through teaching-learning in its true sense.

—

Know more

- Read Lego Foundation’s study on learning through play.

- Understand more about play-based learning and its importance.

- Explore more about play-based learning and its influence on academics.

- Learn more about the draft National Education Policy 2019.