What does ‘gender responsive’ actually mean and how do we ensure that the programmes and interventions we plan, implement, and measure are gender responsive?*

Gender-responsive programming and policies are those that intentionally employ gender considerations to affect the design, implementation, and measurement of programmes and policies. And by doing so, they seek to address the underlying gender norms and barriers that organisations and programmes often have to work around.

The four domains critical to address in gender responsive programmes are:

- Gender norms: These are socially constructed characteristics that have been assigned to people based on their sex. For example, ideas like men don’t cry, or women are sensitive, are examples of gender norms. These norms are internalised early in life and can establish a life cycle of socialisation and stereotyping.

- Gender roles: Based on gender norms and within a specific culture, these are behaviours that are widely considered to be socially appropriate for individuals of a specific sex. These often determine the traditional responsibilities and tasks assigned to people–for example, the notion of men being providers and women, care-takers.

- Gender relations: These are the ways in which a culture or society defines the balance of power between people based on their gender roles. For example, men having decision making capacity within the household, based on the fact that they are expected to be the providers.

- Access to and control over resources: This is the way in which communities or society delineate access and rights over resources–land, finances, assets, property, and so on–based on previously established gender relations. For example, women have less access to resources or land in their name because of the inherent imbalance in power between them and men.

Related article: Backlash: The consequences of defying gender norms

Implementing gender-responsive programming

It is important to incorporate a gender lens at each stage of the programme cycle.

A gender lens is required to examine the differences in roles and norms between women and men, the different levels of power they hold, their differing needs, barriers, bottlenecks, and opportunities, and the impact of these differences on their lives.

It is important to incorporate this lens at each stage of the programme cycle: planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation.*

Planning has two steps: situation analysis or needs assessment, and programme design.

a) Situation analysis or needs assessment

When conducting a situation analysis, one of the first things you need to ensure is that there is a gender analysis built into it. This entails the collection and analysis of quantitative data (numbers, percentages) and qualitative information (preferences, beliefs, attitudes, behaviours) while keeping gender at the forefront.

The analysis can either be a desk review or something more in-depth that includes using participatory methods, key interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs). It is generally completed before the project is initiated, and usually includes three components:

- Collecting gender- and sex-disaggregated data and information (both quantitative and qualitative).

- Analysis of that data (what does the information mean).

- Building gender perspectives (building a cohesive understanding which includes differences in power, needs, constraints, and opportunities, and the impact that these differences have on people’s lives).

A gender analysis helps you become aware of the inequalities that may serve as barriers to achieving the programme’s goals. And once you are aware of these barriers, you can begin to address them.

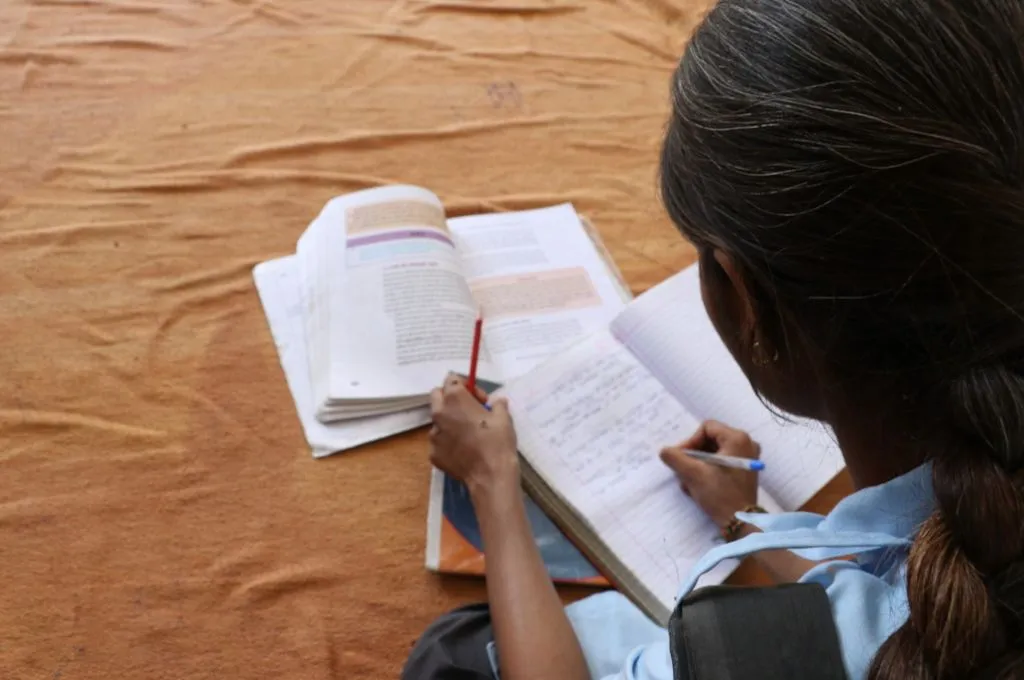

A gender lens is required to examine the differences in roles and norms between women and men, the different levels of power they hold, their differing needs, barriers, bottlenecks, and opportunities | Picture courtesy: Charlotte Anderson

b) Programme design

Once context-specific gender-related barriers, bottlenecks, and opportunities are understood, evidence-based interventions can be developed.

For example, if lack of permission or information by fathers/brothers/male partners is identified as a barrier to girls and women’s participation in programmes, developing an objective to increase male involvement, and reaching men and boys could be seen as a possible solution.

Some questions to be kept in mind during the programme design stage include:

- Have gender-responsive programme actions, that address the inequalities found in the situation analysis, been prioritised?

- Are sex-disaggregated and specific gender indicators included in what the results the intervention aims to achieve? Can they be adequately mapped?

- If they are needed, can partnerships been developed to ensure gender responsive programming actions?

Gender responsiveness in programmes could also be increased by addressing components such as site selection, recruitment of female project staff, involvement of female leadership, inclusion of gender sensitisation content and training, and so on.

Related article: The development discourse in India neglects women

Implementation is where programme planning is made real through a variety of strategies and activities. Examples of gender responsive strategies and activities to include at this stage are:

- Increasing staff capacity on gender analysis and investing in making sure they understand gender norms and roles and how they affect the target community

- Ensuring communication materials are gender sensitive and inclusive

- Having active participation of women in decision making committees and women in leadership positions

- Improving access to services by addressing barriers for women and girls with limited mobility

- Engaging men and boys to address power dynamics, stereotypes and gender norms

Questions to be kept in mind at the implementation stage include:

- Have activities been identified and implemented to achieve the proposed gender outputs and outcomes?

- Have gender responsive implementation approaches been determined for communities?

- Is the programme addressing women and girls’ lack of information and issues of access, mobility and services? Is there special attention being paid to women and girls?

Gender-responsive monitoring using sex- and age-disaggregated data–according to mechanisms set out in the programme design stage–help keep the programme on track. It helps to understand how and why change occurs for people based on their gender, and re-examine interventions and realign strategies in order to be more effective. Corrective measures can be taken if things are not working.

It helps to understand how and why change occurs for people based on their gender.

A gender-responsive evaluation will reveal the outcomes of the programme, including differentiated gender impacts. It will tell implementers whether they have achieved intended results, and what were obstacles to progress. It could help assess the degree to which gender inequalities and unfair power relations change as a result of an intervention. It could also assess gaps in programming, focusing on whether women and girls were effectively reached or not.

Participatory evaluations and mixed approaches that use qualitative and quantitative methods have proven to be beneficial in gathering information. Evaluation findings can provide important lessons and recommendations for refining current and designing future programmes for gender equality.

Moving forward

As planners, funders, and practitioners, it is critical to address gender inequalities in our programme planning and implementation. If not, we will not be able to achieve and reach effective results. Following the steps laid out in this article, programmes can initiate work on advancing gender equality, and hopefully ultimately bring about larger-scale change.

*UNICEF ROSA Gender Toolkit: Integrating Gender in Programming (2018) and UNICEF ROSA Gender Equality Brochure (2018).